In 1903, residents of the small town of Dexter, Kansas, gathered to celebrate a newly drilled natural gas well.

Crowds flocked to the well for the lighting of the escaping gas, which officials had said would produce “a great pillar of flame.” But when they rolled a burning bale of hay onto the well, nothing happened.

An analysis in 1905 revealed that most of the gas was nonflammable nitrogen, just 15% was methane — and a little less than 2% was a colorless, odorless, elusive element that scientists had discovered only a few decades earlier. This marked the first discovery of helium in a natural gas field.

Today, helium is an essential cooling component in nuclear reactors, rockets and medical diagnostic equipment such as MRI machines. The gas keeps fiber optics, superconductors, quantum computers and semiconductors cool, but skyrocketing demand has pushed supply chains to their limit, resulting in a global shortage that has persisted for more than a decade. Helium extraction also has a huge carbon footprint — almost equivalent to the U.K.’s per year — because currently, it is exclusively produced together with natural gas.

However, in recent years, pioneering discoveries have led to a pivotal change in scientists’ understanding of the geology that helps helium accumulate. Researchers have uncovered reservoirs of primary, “carbon-free” helium — large accumulations of the gas that are highly concentrated and don’t contain methane — that could revolutionize the industry.

This new understanding has fueled exploration projects in a handful of regions around the world. From Yellowstone to Greenland to the East African Rift, a helium “rush” is starting to address shortages and helium’s enormous carbon footprint.

“It’s a new industry,” Thomas Abraham-James, co-founder and CEO of the exploration company Pulsar Helium, told Live Science.

Perfect seals, imperfect yields

After World War I, helium discoveries multiplied and the U.S. emerged as the world’s leading producer. Gas wells with helium levels of 0.3% and above were tapped to fuel a growing number of industries and form a stockpile, the Federal Helium Reserve in Amarillo, Texas. (The stockpile was sold in 2024 to the industrial gas firm Messer.)

But helium has been produced only as a minor byproduct, usually found in tiny amounts mixed in with natural gases such as methane.

That’s because gases like methane and carbon dioxide (CO2) are required to transport helium from the middle part of Earth’s crust to shallower regions, Chris Ballentine, a professor of geochemistry at the University of Oxford, told Live Science in an email.

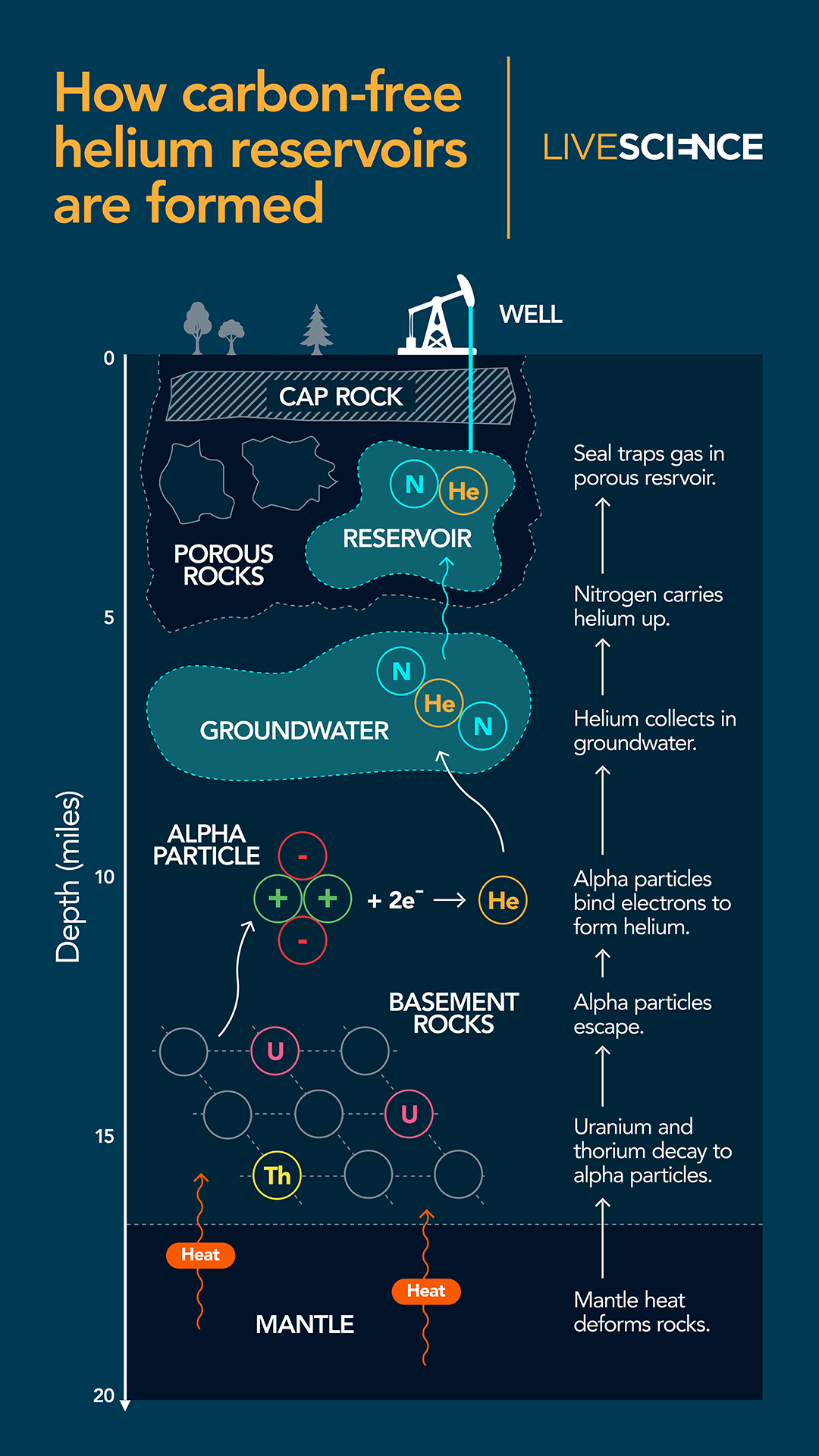

Helium forms in the top 16 miles (25 kilometers) of Earth’s crust when uranium and thorium break down into other radioactive elements, emitting alpha particles, or helium nuclei, in the process. These helium nuclei gain two electrons from atoms in their environment to form helium atoms, which then migrate and gradually collect in groundwater down to 10 miles (16 km) below Earth’s surface, Ballentine said.

But for helium atoms to form a gas, they need to reach their “bubble point” — the concentration of a dissolved gas in a liquid required to make buoyant gas bubbles. Helium in groundwater rarely accumulates in sufficient quantities to reach this bubble point, Ballentine said. So other, more ubiquitous gases, like methane and CO2, are typically needed to entrain helium and form the bubbles that rise toward geological traps, Ballentine said.

These geological traps are often natural gas fields. But helium also gets trapped, because natural gas fields often have strong seals, research suggests.

Natural gas reservoirs form beneath layers of fine-grained “cap” rocks “and minerals. In Australia’s Amadeus Basin, for example, helium and natural gas are locked beneath a thick layer of salt, which is a “perfect” seal, Jon Gluyas, a professor of geoenergy, carbon capture and storage at Durham University in the U.K., told Live Science.

Most places, however, don’t have a perfectly sealed reservoir to trap helium underground, so the gas escapes into the atmosphere. “All systems are leaky,” Gluyas said. As a result, most regions with helium-producing rocks emit some helium, so “if you went out with a sensitive enough instrument, you would find it,” he said.

Helium’s association with natural gas means producers can extract both at the same time, but this approach has major drawbacks. For one, the helium industry currently has an indirect carbon footprint of about 350 million tons (320 million metric tons) per year, which is bigger than all but 20 countries’ carbon footprints.

A second downside is that countries with natural gas deposits and the companies drilling these deposits control the world’s supply of helium. The U.S. used to dominate global helium production, but Qatar took the lead in 2022. Depending on other countries for helium introduces risks related to regional geopolitics, Gluyas said. Algeria and Russia are also leading helium producers, raising similar concerns.

But the biggest problem with helium extraction is that natural gas contains minuscule amounts of helium. In the U.S., the lower profitable limit to separate helium from natural gas is 0.3%, but some countries with different production and transport methods have much smaller thresholds. For example, Algeria’s Hassi R’Mel gas field contains 0.19% helium and Qatar’s North Dome deposits contain 0.04% helium, yet both countries extract helium at these locations.

Groundbreaking discoveries

Data show that only about 1 in 6 natural gas reservoirs in the U.S. has helium levels higher than 0.3% and that levels above 7% are extremely rare, meaning economically useful helium concentrations are the exception in the U.S.

The trend is similar in other countries. So when scientists found a nitrogen gas reservoir that contained up to 10.4% helium in Tanzania in 2016, they were flabbergasted. The gas was bubbling out of the ground in the Rukwa Rift Basin, which is located on a divergent plate boundary called the East African Rift.

Crucially, the Rukwa Rift Basin doesn’t have reservoirs of natural gas or other hydrocarbons. This was the first major confirmed discovery of a hydrocarbon-free helium reservoir, and it sparked an ongoing worldwide hunt for other such reservoirs.

Ballentine, Gluyas and Abraham-James were part of the team that made the discovery in Tanzania. “The approach we adopted essentially is similar to that which any explorer would use for petroleum — we went looking for seeps,” Gluyas said. Helium seeps are “all over the show,” he said, but locating them is trickier than finding petroleum because helium is odorless, colorless and usually at low concentrations.

From then on, researchers and exploration companies tried to determine whether known helium seeps led to hydrocarbon-free reservoirs with high concentrations of the noble gas. In 2021, for example, the exploration company Pulsar Helium acquired land near Babbitt, Minnesota, where a company searching for nickel had previously found gas with high helium concentrations. Pulsar Helium drilled a well down to 2,200 feet (670 meters) in early 2024 and found a huge gas reservoir with helium concentrations up to 14.5% — the highest the industry has ever seen in North America.

The other gases in the reservoir were nitrogen and CO2. But the site contains no natural gas, so it counts as a primary helium accumulation, Pulsar Helium representatives say. CO2 concentrations were above 70%, but the company views this as an opportunity rather than a problem, because the gas is pure enough to be used for carbonated beverages, water treatment, food preservation and medicine.

Unique geology

The more reservoirs of hydrocarbon-free helium that researchers and companies find, the more information they learn about the geology that forms these reservoirs. Shortly after the discovery in Tanzania, geologists identified five key conditions needed to form accumulations of helium without natural gas.

First, the region must have helium-producing rocks miles below the surface. The best helium source rocks are ones that contain uranium or thorium, and are usually composed entirely of crystallized minerals, Gluyas, Ballentine and their colleagues wrote in a 2024 article for the Energy Geoscience Conference Series.

That’s because crystalline rocks solidify from magma cooling extremely slowly underground. This unhurried process concentrates radioactive uranium and thorium, which are unstable elements in mineral structures and therefore among the last to be incorporated. Granite is one of the best helium sources, Ballentine said.

Ideally, the rocks should also be hundreds of millions to billions of years old, because the radioactive versions of uranium and thorium that decay into alpha particles have half lives of 4.5 billion and 14 billion years, respectively, according to the article. That means it would take that long for half of a sample of those elements to decay into helium. As a result, it takes millions of years to accumulate enough helium to fill a large reservoir.

The second criterion needed to form a hydrocarbon-free helium reservoir is a heat source around the rocks.

Normally, helium is frozen in a mineral’s lattice structure because that structure is “blocked” — or doesn’t exchange molecules with its surroundings. For minerals to release that helium, they must exceed their “closure temperature” — the temperature at which the lattice becomes unblocked. That temperature varies, but can be above about 160 F (70 C) for one of the most common helium-containing minerals.

Often the source of heat is volcanism or geothermal heat, so hydrocarbon-free helium reservoirs typically occur in regions where there is, or once was, volcanism. Beneath the Rukwa Rift Basin, for example, eastern Africa is pulling away from the rest of the continent, causing magma to rise to the surface. Similarly, Pulsar Helium’s exploration site in Minnesota sits on an ancient tear in North America’s crust called the Midcontinent Rift System. This rift system started and then failed about 1.1 billion years ago, producing intense volcanic activity during the roughly 100,000 years it was active.

The third condition to form a hydrocarbon-free helium reservoir is the presence of nitrogen in groundwater, because nitrogen bubbles can transport helium upward through the crust in the same way methane and CO2 bubbles can, while completely removing greenhouse gases.

The fourth condition is the need for relatively airtight “cap rocks” that sit near the surface above the helium-forming rocks in Earth’s crust. That’s because when nitrogen reaches its bubble point, it captures helium atoms and taxies them until the gases either escape into the atmosphere or are trapped. But for that to happen, the cap rocks must form an impermeable seal.

The fifth and final condition is that these cap rocks must sit atop fractured, porous “reservoir” rocks that can store gas, Ballentine, Gluyas and their colleagues wrote in the 2024 article.

The growth rate of a reservoir depends on the rates at which gases enter from below and escape via cracks in the seal, the researchers wrote. The more helium that enters a reservoir and the less that escapes through the seal, the bigger an accumulation can get. In other words, reservoirs ideally have porous or highly fragmented rocks down below, and nonporous, intact rocks above.

Helium reservoirs with impermeable seals can hold gases for long periods of geological time. For example, the link between the reservoir in Minnesota and the Midcontinent Rift System suggests helium has been building up there for 1.1 billion years.

Appraisal and development

Pulsar Helium recently announced that it will start engineering work for a helium production plant at its site in Minnesota, signaling that hydrocarbon-free, U.S.-produced helium could reach the market in just a few years.

Early this year, the company more than doubled the depth of its first well to reach the bottom of the reservoir and drilled a second well down to 5,638 feet (1,718 m). Tests over the summer showed high flow rates to the surface and stable helium concentrations of up to 8% at both wells, “providing a robust foundation for future development,” Abraham-James said in a September statement. Since then, Pulsar Helium has drilled an additional well down to 3,507 feet (1,069 m) and opened two more wells.

Pulsar Helium is also progressing with a helium project in East Greenland — the first helium discovery on the island, Abraham-James told Live Science.

“What we’ve learned in Minnesota and elsewhere, we then applied it to Greenland and we found the helium there,” he said. “Like Minnesota, its helium is not associated with hydrocarbons. We conducted a seismic survey last year, and that went some ways to mapping the reservoir.”

Located about 3 miles (5 km) from the coastal settlement of Ittoqqortoormiit, the site in East Greenland looks promising for helium and geothermal energy production, which could limit the settlement’s dependency on fossil fuels, Abraham-James said. Mapping in 2024 revealed a zone of crust with temperatures reaching 266 F (130 C), as well as a fractured reservoir that researchers linked to gas emissions at the surface containing up to 0.8% helium, according to a statement from Pulsar Helium.

Any helium produced in East Greenland would likely go to the local community, Abraham-James said. Similarly, helium produced in Minnesota would be sold inside the U.S. to supply MRI scanners, semiconductor fabrication and space launches, he said.

Helium shortages in the U.S. have eased somewhat since early 2024, partly thanks to additional supplies from natural gas fields, said Nicholas Fitzkee, a professor of chemistry at Mississippi State University. “But having a larger domestic supply would be valuable, because it could insulate the U.S. from geopolitical instabilities that have contributed to past helium shortages,” Fitzkee told Live Science in an email.

Halfway across the globe, prospecting in Tanzania is also ongoing, with two exploration companies currently reporting helium levels of 5.5% and 2.46% at different ends of the Rukwa Rift Basin. Called Helium One Global and Noble Helium, these companies are still in the early phases of exploration, Gluyas said.

“Both Helium One and Noble Helium have successfully shown elevated concentrations of helium in the wells they’ve drilled,” he said. But these wells don’t provide a clear picture of the reservoir yet, and the reservoir may not end up fulfilling researchers’ expectations.

“They could speculate, based upon the seismic information, what the geometry of the accumulation might be, but they haven’t yet drilled sufficient wells to say, ‘It really is that,'” Gluyas said.

Beyond Tanzania, there may be opportunities for helium exploration in India’s Bakreswar-Tantloi geothermal area, which is located in the east of the country and straddles the states of West Bengal and Jharkhand. The Bakreswar-Tantloi area sits on ancient granitic rocks that are rich in uranium and therefore produce helium. The region also has a fault system and a high heat gradient as a result of ongoing tectonic activity along the Son-Narmada-Tapti rift zone, research suggests.

Closer to home, researchers are analyzing the conditions for potential helium accumulations beneath and around Yellowstone National Park. Yellowstone is rooted in the Wyoming Craton, a prehistoric region of crust and upper mantle that contains 3.5 billion-year-old rocks known to produce huge quantities of helium. Thanks to Yellowstone’s countless geothermal features and volcanic structures, helium may be accumulating in reservoirs beneath or peripheral to the park, although it’s more likely that the gas is circulating and escaping into the atmosphere through a complex system of natural pipes.

“What’s happened over the millions or hundreds of millions of years in the area in which Yellowstone occurs is that helium has been building up, and now in the last [roughly] 5 million years, the supervolcano beneath is flushing it out,” Gluyas explained.

That means the chances of extracting this helium are remote, not least because of the scorching temperatures of up to 275 F (135 C) that drillers would encounter belowground. “Will your drilling equipment survive? Almost certainly not,” Gluyas said.

But beyond Yellowstone, it’s important for existing hydrocarbon-free helium projects to complete their evaluations and start selling the gas as soon as possible, Gluyas said. “There is a huge need for helium,” he said.

However, Fitzkee sees another way forward — rolling out technologies that can recycle or lower our helium consumption. That could be through installing helium recovery systems or engineering room-temperature alternatives to current helium-hungry technologies, he added.

Topping up our helium supply is a good stopgap solution, but not a permanent fix, he argued.

“Ultimately, we cannot mine our way out of future helium shortages,” he said. “Helium is non-renewable, and we have no easy way to make more at scale.”