Colossal monsters lurk in the centers of all galaxies. Known as supermassive black holes, these gravitational beasts can have millions to billions of times more mass than the sun.

For decades, astronomers have wondered where these behemoths came from and how they got so huge. Early on, physicists thought that supermassive black holes formed like other, smaller black holes do — with large stars collapsing and becoming sun-size black holes that slowly devoured surrounding matter and merged with one another over billions of years.

Emerging research suggests enormous black holes could have existed since the universe’s earliest days, perhaps even before stars and galaxies, and that they came about in multiple ways. While future discoveries will help narrow down the predominance of each formation mechanism, many in the field are already thrilled to be chipping away at a long-standing cosmic mystery.

“This is one of the most exciting phases of my career,” Roberto Maiolino, an astrophysicist at the University of Cambridge, told Live Science. “I’m tempted to call it a real revolution in our understanding of the formation of these objects.”

Mystery giants

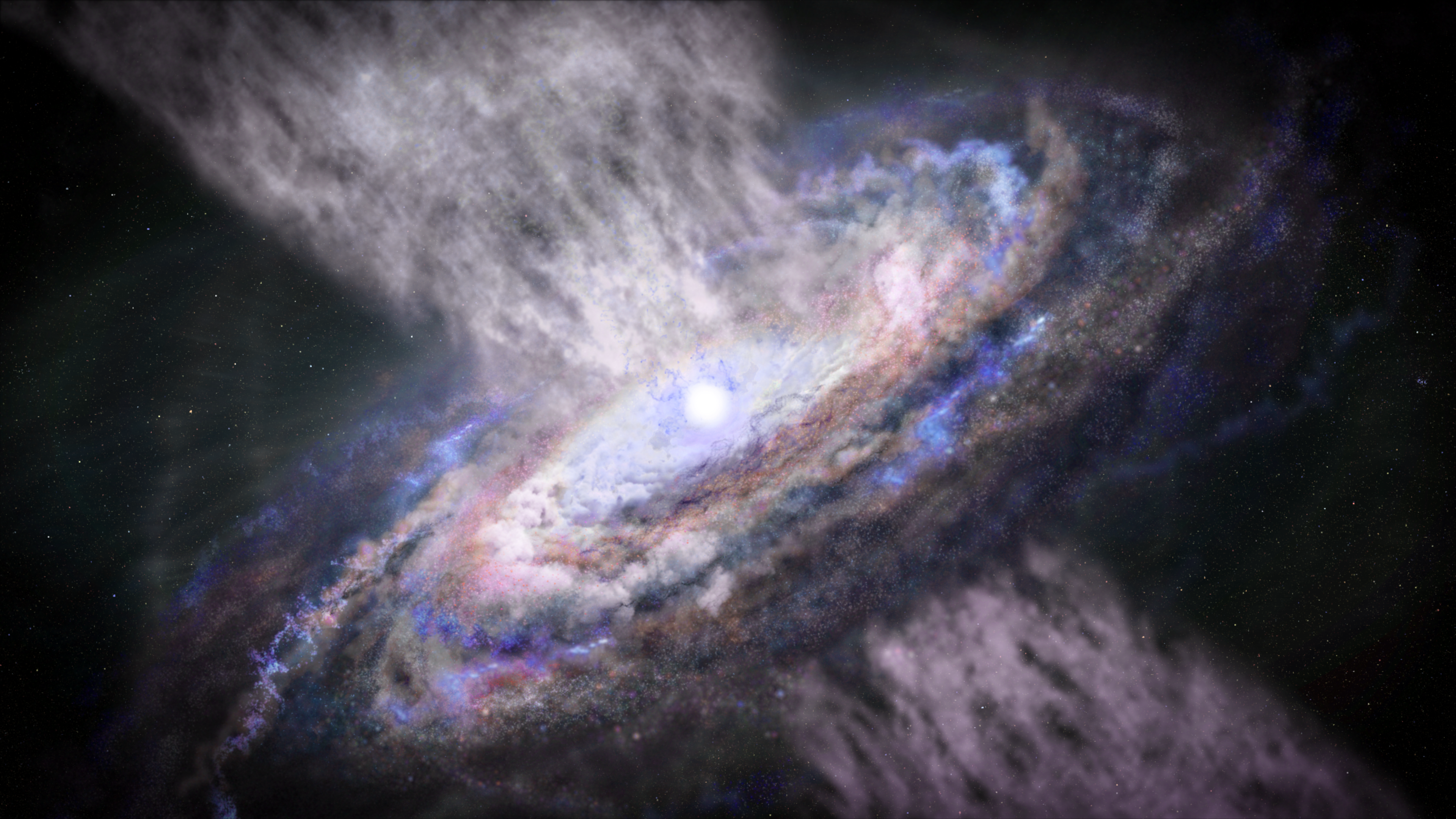

Hints of the cosmic size discrepancy arose in the early 2000s, when instruments like the Sloan Digital Sky Survey helped capture data on tens of thousands of extremely bright objects called quasars in the faroff universe. These luminous entities are thought to be gargantuan black holes in the centers of galaxies. They feed on vast amounts of gas and dust, and then spew powerful radiation. The Sloan survey showed that many quasars existed when the universe was just 800 million years old — a fraction of its current 13.8 billion-year age. The existence of these behemoths, which have millions to billions of times the sun’s mass, was a head-scratcher for cosmologists.

That’s because a typical black hole arises when a huge star nears the end of its life and explodes as a fiery supernova. The core of the titanic star collapses into a superdense point from which nothing, including light, can escape. Such stellar-size black holes are generally around 10 to 100 times as massive as the sun. While these objects can become gravitationally attracted to one another and merge into ever larger black holes, there didn’t appear to be enough time for such processes to build them up into quasar-scale territory at the earliest points in cosmic history.

“We knew that either they grow very fast or there had to be some other ways of forming them,” astrophysicist Ignas Juodzbalis, also of the University of Cambridge, told Live Science.

The question was how. One leading theory posits that, in the past, ginormous clumps of gas and dust could collapse under their own weight, rapidly forming a black hole with perhaps 1,000 to 1 million times the sun’s mass. These direct-collapse black holes, as they’re called, would then grow by feeding on gas and dust and merging into the supermassive black holes seen in today’s galactic centers.

Models predicted that as such black holes gorged, they would become extremely bright compared with their host galaxies, either matching or topping surrounding stars’ luminosities. In other words, they would become quasars.

In 2023, JWST spotted a distant galaxy, dubbed UHZ1, that seemed to align neatly with the direct-collapse black hole model. The galaxy existed when the universe was a mere 470 million years old and contains a black hole with an estimated mass of 40 million suns.

Astronomers lucked out because UHZ1 was spotted both by JWST, which sees in the infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum, and by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, which sees in X-ray light. Infrared light mostly comes from stars and warm dust heated by starlight, whereas the more powerful X-rays blast out from the devouring black hole.

And UHZ1’s infrared and X-ray brightness are quite similar to one another, which suggests a black hole so large that it rivals the mass of all the stars in its galaxy. (For comparison, a modern galaxy like our Milky Way has around 20,000 times more mass in its stars, gas and dust than in its central black hole.) No one had ever seen anything like this before.

But researchers had predicted exactly how the colors emitted by a direct-collapse black hole would appear in JWST’s instruments, along with several other key properties that could identify such an object .

“It turns out that UHZ1 remarkably satisfies all these properties,” Priyamvada Natarajan, an astrophysicist at Yale University and lead author of the paper making those predictions, told Live Science.

Little red dots

UHZ1 is not alone. From almost the moment it turned on, JWST has been detecting extremely compact red entities that existed mainly when the cosmos was between half a billion and 1.5 billion years old. Known as “little red dots,” they were originally thought to be galaxies far too big to have formed in the early universe, leading some scientists to call them “universe breakers” for upending models of cosmic history. The prevailing consensus is now moving toward the possibility that, rather than unusually large galaxies, these are bizarre, humongous black holes.

For instance, an object called QSO1 that existed when the universe was around 700 million years old has been studied intensely since it was discovered in 2023. A recent investigation looked at gas swirling around QSO1’s center to try to pin down its mass with high precision. Swirling gas travels at a certain speed depending on the gravitational force tugging it as it spins. Using this technique, astronomers have shown that QSO1’s mass is around that of 50 million suns. Moreover, all of the mass appears to be in a compact region around the black hole, with very little evidence of a large stellar population.

“We still don’t see where the host galaxy is,” Lukas Furtak, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science. “There doesn’t really seem to be one.”

This prospect — a gigantic black hole with no visible host galaxy — has been conjectured but never previously observed. Yet that appears to be what many of these little red dots are. Another recent study analyzed an object named “The Cliff,” which likely weighs billions of times as much as the sun and is from about 1.8 billion years after the Big Bang. JWST’s data showed a very sharp jump in The Cliff’s light at a narrow wavelength that usually arises from dense hydrogen gas at a specific temperature. The findings indicate that The Cliff might be a long-hypothesized object called a quasi-star or a black hole star.

A quasi-star would be a potential stage in the evolution of a direct-collapse black hole. After the central huge chunk of gas crumpled to form a black hole, an outer sphere of gas and dust would remain, get heated by the black hole’s emissions and glow in red wavelengths. This entity would look somewhat like a giant red star but would in fact be an envelope of hot hydrogen gas cocooned around a supermassive black hole.

In the very beginning

While direct-collapse models can explain a lot of what JWST is seeing, there remain a few other possibilities for supermassive black hole formation.

First proposed by Stephen Hawking in the 1970s, primordial black holes are a class of objects that could have arisen in the first few moments after the Big Bang, when dense regions collapsed under their own weight. Such black holes could come in a wide range of sizes, including ones large enough to act as the initial seeds for later supermassive black holes. One study has shown that mergers of primordial black holes could explain GN-z11, a galaxy from when the universe was a mere 400 million years old that contains a black hole with an estimated mass of 2 million suns.

Another theory has posited the existence of “not-quite-primordial black holes .” These would have come about within the first few million years after the Big Bang — later than primordial black holes but still long before any stars — when large clouds of hydrogen and helium collapsed under their own weight.

“For primordial black holes, you need these really extremely dense regions in the very early universe,” Wenzer Qin, a theoretical physicist at New York University, told Live Science. That generally requires a lot of fine-tuning of parameters in a cosmological model, she added. When you relax such tight constraints a bit, dense regions appear at slightly later times in cosmic history, creating direct-collapse black holes that can go on to merge and end up as supermassive black holes.

Astronomers think that almost all elements heavier than hydrogen and helium were created in the nuclear bellies of giant stars and were then strewn about the universe when those stars went supernova. Many of the early black holes and young galaxies that JWST is seeing contain low amounts of these heavy elements. That could suggest that at least some of these objects formed from either primordial or not-quite-primordial black holes, given that both would have arisen long before any stars existed.

Researchers are still debating which of these models might be dominant for monster-black-hole formation, but most favor a blended view.

“I think, in the end, it will be some combination of all these mechanisms that gives rise to the entire population of supermassive black holes,” Qin said.

Other missions such as the European Space Agency’s Euclid observatory, launched in 2023, and NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, expected to launch in 2027, will team up with JWST to discover and study more early supermassive black holes. That should help researchers differentiate between these formation mechanisms and determine which, if any, is more common.

One thing that appears to be growing clearer to many astronomers is that supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies probably didn’t come from stellar-size ones.

Thanks to its unparalleled abilities, JWST has upended our understanding of early cosmic history and is helping to rewrite the story of how gigantic black holes may have developed.

“The universe is littered with supermassive black holes that form extremely early,” Natarajan said. “I can’t tell you how exciting that is.”