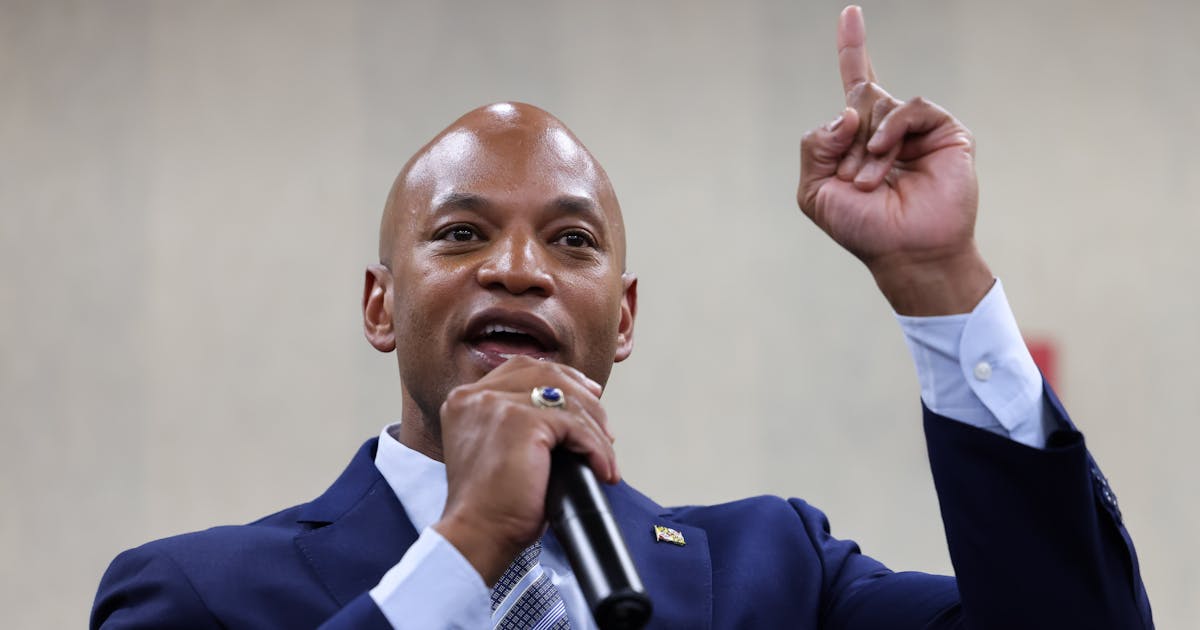

But here’s the rub: The bill that Moore spiked was never actually about discovering new facts to lay alongside the vast mountain of already-obtained knowledge. Rather, it’s a quintessentially American ritual. A performance of forward motion that, in reality, preserves the status quo: activity masquerading as achievement. We are not waiting for more data. We are waiting for the willpower of political elites to catch up to the facts we have already gathered about the state of the world. We are hoping that we might create a force strong enough to dissolve the lucrative web of mutual dependence that exists between politicians, their funders, and their funding recipients—an arrangement that allows the few to profit from the entrenched policies that impoverish the many.

For much of my lifetime, the nation, like our tech devices, has operated like a machine engineered for planned obsolescence: appearing functional on the surface but designed to slowly degrade beneath the hood. Our dissatisfaction is tempered by the allure of a shiny new upgrade that promises new features each campaign cycle. Like our top-grossing movies, election cycles are reboots and franchises. That includes our politics. Our institutions don’t just fail; they are built to delay, to degrade, to defer. We pretend they work, and when they don’t, we hold another hearing, commission another report, launch another study, believe another promise.

Moore is hardly the first to challenge these neglectful impulses. More than a decade ago, The Atlantic published Ta-Nehisi Coates’s landmark essay “The Case for Reparations.” It was not merely a manifesto but a meticulous historical excavation—from redlining in Chicago to the GI Bill’s racist exclusions—that laid out in irrefutable detail how government policy, not just private prejudice, created Black disadvantage. It forced a national conversation. But again, the response was mostly talk.