More than 2 billion years ago, long before Earth’s atmosphere contained oxygen, one hardy group of microbes may have already evolved to live with the gas, setting the stage for the rise of complex life.

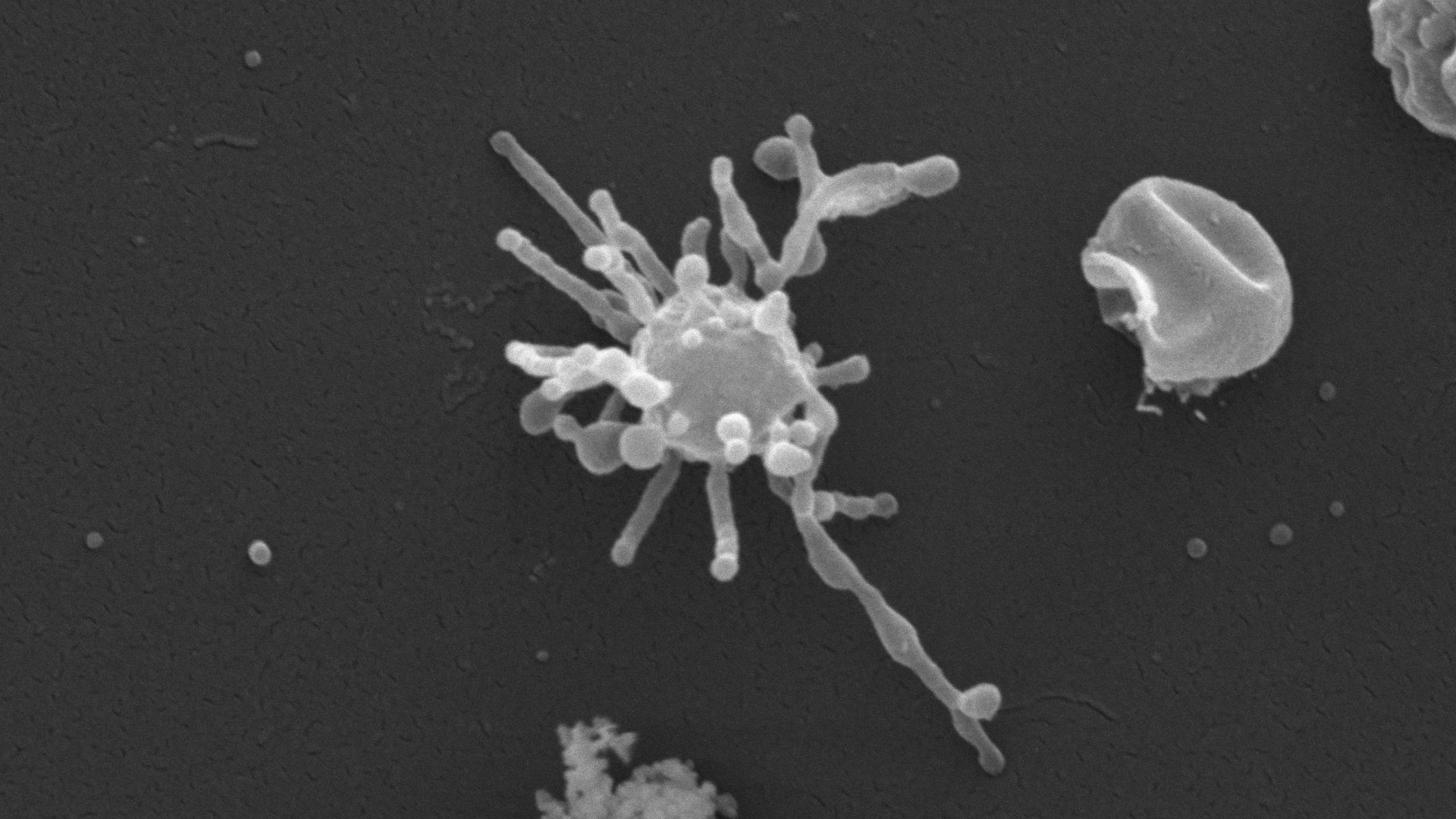

In a new genetic survey of ocean mud and seawater, researchers found evidence that the closest known microbial cousins of plants and animals — a group known as Asgard archaea — carry the molecular gear to handle oxygen, and possibly even convert it into energy. Previously, many Asgards studied were associated with oxygen-poor areas.

Mitochondria, the energy hubs inside complex cells, came from a bacterium which needs oxygen to survive. But archaea — one of the three large domains of life— are thought to be the hosts in the important microbe-meets-bacterium story — and many of them seemed to be built for surviving without oxygen. The new study, published Feb. 18 in the journal Nature, suggests that the microbe host, known as Asgard archaea, may have tolerated oxygen better than previously thought.

“Most Asgards alive today have been found in environments without oxygen,” study co-author Brett Baker, an associate professor of marine science at the University of Texas at Austin, said in a statement. “But it turns out that the ones most closely related to eukaryotes live in places with oxygen, such as shallow coastal sediments and floating in the water column, and they have a lot of metabolic pathways that use oxygen. That suggests that our eukaryotic ancestor likely had these processes, too.”

Asgard archaea, named after the dwelling place of the gods in Norse mythology, were discovered in 2015 when researchers assembled genomes from deep-sea sediments near the Loki’s Castle hydrothermal vent. From this research, the team created an Asgard superphylum which included archaeal groups like Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota and Odinarchaeota. Follow up studies revealed that Asgards appeared to carry multiple “eukaryotic signature” genes, suggesting a close ancestral tie to eukaryotes, organisms whose cells have a nucleus and membrane-bound organelles.

A deep-sea journey

To understand how Asgards may have tolerated oxygen, the team hunted in the Bohai Sea at 100 feet (30.5 meters) below sea level and in the Guaymas Basin at 6,561 feet (2,000 meters) below sea level, areas where microbes thrive. They sifted through and analyzed roughly 15 terabytes of environmental DNA from marine sediments, rebuilt more than 13,000 microbial genomes, and pulled out hundreds of genetic sequences that belong to the Asgards.

“These Asgard archaea are often missed by low-coverage sequencing,” study co-author Kathryn Appler, a postdoctoral researcher at the Institut Pasteur in Paris, said in the statement. “The massive sequencing effort and layering of sequence and structural methods enabled us to see patterns that were not visible prior to this genomic expansion.”

Those patterns included genes linked to aerobic respiration, the oxygen-powered process many organisms use to squeeze extra energy from food. The team also used an AI tool called AlphaFold2 to predict protein shapes and strengthen their case for genetic machinery that was oxygen-tolerant inside the microbe.

In particular, one branch of the Asgards, known as Heimdallarchaeia (named for the watchman of the Norse gods), stood out. The researchers reported that many Heimdallarchaeia genomes contain parts of the molecular machinery used to move electrons and generate energy with oxygen, along with enzymes that help manage toxic oxygen byproducts.

If these oxygen-handling abilities were present in the archaeal ancestor of complex cells, it makes the famous merger easier to picture.

“Oxygen appeared in the environment, and Asgards adapted to that,” Baker said. “They found an energetic advantage to using oxygen, and then they evolved into eukaryotes.”

Appler, K. E., Lingford, J. P., Gong, X., Panagiotou, K., Leão, P., Langwig, M. V., Greening, C., Ettema, T. J. G., De Anda, V., & Baker, B. J. (2026). Oxygen metabolism in descendants of the archaeal-eukaryotic ancestor. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-026-10128-z