Editor’s note: This article is part of a special package written for the 50th anniversary of the discovery of a 3.2 million-year-old A. afarensis fossil (AL 288-1), nicknamed “Lucy.”

About 3.2 million years ago, our ancestor “Lucy” roamed what is now Ethiopia.

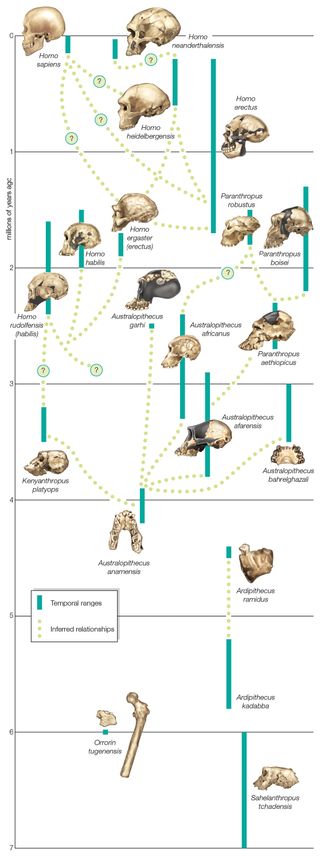

The discovery of her fossil skeleton 50 years ago transformed our understanding of human evolution. But it turns out her species, Australopithecus afarensis, wasn’t alone.

In fact, as many as four other kinds of proto-humans roamed the continent during Lucy’s time. But who were Lucy’s neighbors, and did they ever interact with her kind?

For almost a million years, A. afarensis lived throughout East Africa, and paleoanthropologists have found numerous fossils of this species ranging from north central Ethiopia to northern Tanzania — a span of 1,460 miles (2,350 kilometers), or roughly the distance from Boston to Miami.

“It was a highly successful species that was comfortable in lots of different habitats,” Donald Johanson, a paleoanthropologist at Arizona State University who, along with his graduate student Tom Gray, discovered Lucy’s fossils in 1974, told Live Science.

For decades after Lucy’s discovery, paleoanthropologists assumed A. afarensis was the only hominin that lived in this region during the middle Pliocene epoch (3 million to 4 million years ago). But the discovery of a fragmentary jawbone in the Bahr el Ghazal region of Chad in 1995 dramatically changed the picture of hominin diversity.

At 3.5 million years old, this fossil of a species that would be named Australopithecus bahrelghazali was the first indication that other hominins lived around Lucy’s time, Yohannes Haile-Selassie, director of Arizona State University’s Institute of Human Origins, and colleagues wrote in a study published in the journal PNAS in 2016.

Lucy’s kind may not have interacted with these australopithecines, who were more than 1,500 miles (more than 2,400 km) away. But at the site of Woranso-Mille, just 30 miles (48 km) north of where Lucy was found at the site of Hadar in Ethiopia, Haile-Selassie and colleagues found A. afarensis fossils along with other, anatomically distinct fossils from the same time period.

These fossils belonged to a new australopithecine species: Australopithecus deyiremeda, which was dated to between 3.5 million and 3.3 million years ago. A. deyiremeda had markedly different teeth than Lucy’s species, suggesting they had different diets, but paleoanthropologists do not currently agree on whether it is a different species from Lucy.

Woranso-Mille also yielded a partial foot dated to between 3.4 million and 3.3 million years ago, and its opposable big toe suggests this individual was better adapted for climbing than A. afarensis, a species that habitually walked on two legs. Although this individual was clearly not a member of A. afarensis, the “Burtele foot” has not yet been assigned to a species.

And at the Lomekwi site on the bank of Lake Turkana in Kenya, Meave Leakey, director of Plio-Pleistocene research at the Turkana Basin Institute in Kenya, and colleagues discovered another middle Pliocene hominin. The researchers named it Kenyanthropus platyops, Greek for “flat face”. Dated to between 3.3 million and 3.2 million years ago, K. platyops overlapped in time with Lucy but lived over 620 miles (1,000 km) away.

K. platyops‘ brain was similar in size to that of A. afarensis, and the species lived in a grassy, lake-edge environment, much like Lucy did. While some researchers think K. platyops might be a Kenya-specific version of A. afarensis, others, including Haile-Selassie, think its upper teeth are different enough to call it a separate genus and species.

“A closer look at the currently available fossil evidence from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Chad indicates that Australopithecus afarensis was not the only hominin species during the middle Pliocene, and that there were other species clearly distinguishable from it by their locomotor adaptation and diet,” Haile-Selassie and colleagues wrote.

This growing collection of fossils from different hominin species raises an important question that paleoanthropologists are trying to answer: Did these different species meet, or even mate with each other?

Almost all primates are social creatures, living in groups and cooperating to forage for food. And some nonhuman primates, such as tamarins, marmosets and howler monkeys, mate across species.

A. afarensis was as social as other primates, and Lucy may have lived in a group of 15 to 20 males and females. A preserved trail of footprints from three australopithecines walking together at the site of Laetoli in Tanzania is further evidence that Lucy and her kind were social creatures.

But there is currently little hard evidence that australopithecines mated across species, Rebecca Ackermann, a biological anthropologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, told Live Science in an email.

That said, “there is morphological evidence consistent with hybridisation in A. afarensis,” particularly in the variation in their teeth,” Ackermann noted. But these differences cannot be conclusively tied to interbreeding by current DNA techniques because australopithecine fossils are too old to harbor usable DNA.

Instead, we may be able to infer whether they ever interbred by looking at ancient proteins, which are coded for by DNA, she said. By looking at proteins in tooth enamel, Ackermann and colleagues clarified how individuals from the hominin species Paranthropus robustus, which lived in South Africa 2 million years ago, were related.

Despite the vast number of A. afarensis fossils discovered over the past half century, paleoanthropologists still have a lot of work ahead of them to fully understand the world Lucy inhabited.

“How these hominins were related to one another, how they interacted, how they filled niches on the landscape, and the degree of interbreeding that may have happened are open and important questions,” Jeremy DeSilva, a biological anthropologist at Dartmouth College, told Live Science.