A vaccine designed to fight HPV-driven head and neck cancers has shown promising results in a lab study in human tissues and mice.

If proven effective in humans, the therapeutic shot could complement standard cancer therapies, and its design may help scientists build better vaccines for other diseases.

The vaccine Gardasil 9 can prevent HPV infections and thus reduce the risk of these cancers down the line. But for people who already have HPV-related tumors, treatment still relies on surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. Combining a cancer vaccine with these conventional therapies could enhance their effectiveness by teaching the immune system to fight the cancer.

Now, scientists have engineered a cancer vaccine whose components are arranged in a unique structure. Similar to preventive vaccines, cancer vaccines train the immune system to recognize specific proteins — in this case, a protein found on HPV-positive tumors — and often contain ingredients called adjuvants that rev up the immune response. Rather than preventing the disease in the first place, though, cancer vaccines are generally used to treat the disease and help prevent its recurrence.

In lab studies of HPV-positive head and neck cancer, this new, carefully crafted vaccine slowed tumor growth and improved survival in mice, according to a study published Wednesday (Feb. 11) in the journal Science Advances.

Dr. Ezra Cohen, a head and neck cancer specialist at UC San Diego Health who was not involved in the study, said that if the vaccine works in humans, it could complement standard therapies.

“One can imagine a multi-modality approach to render a patient disease-free and then the vaccine to prevent recurrence,” he said. But he cautioned that results in lab animals and isolated tissues don’t always translate to humans. “The real test is in people,” he told Live Science in an email. “But strong preclinical data, like these, make the chances of success in clinical trials higher.”

In this case, the vaccine’s underlying design is notable.

“The key finding is that the structure of the vaccine makes a significant difference,” Cohen said. “Successful vaccination is not just about selecting the correct antigens [target proteins] but placing those antigens in the right sequence with other vaccine elements.”

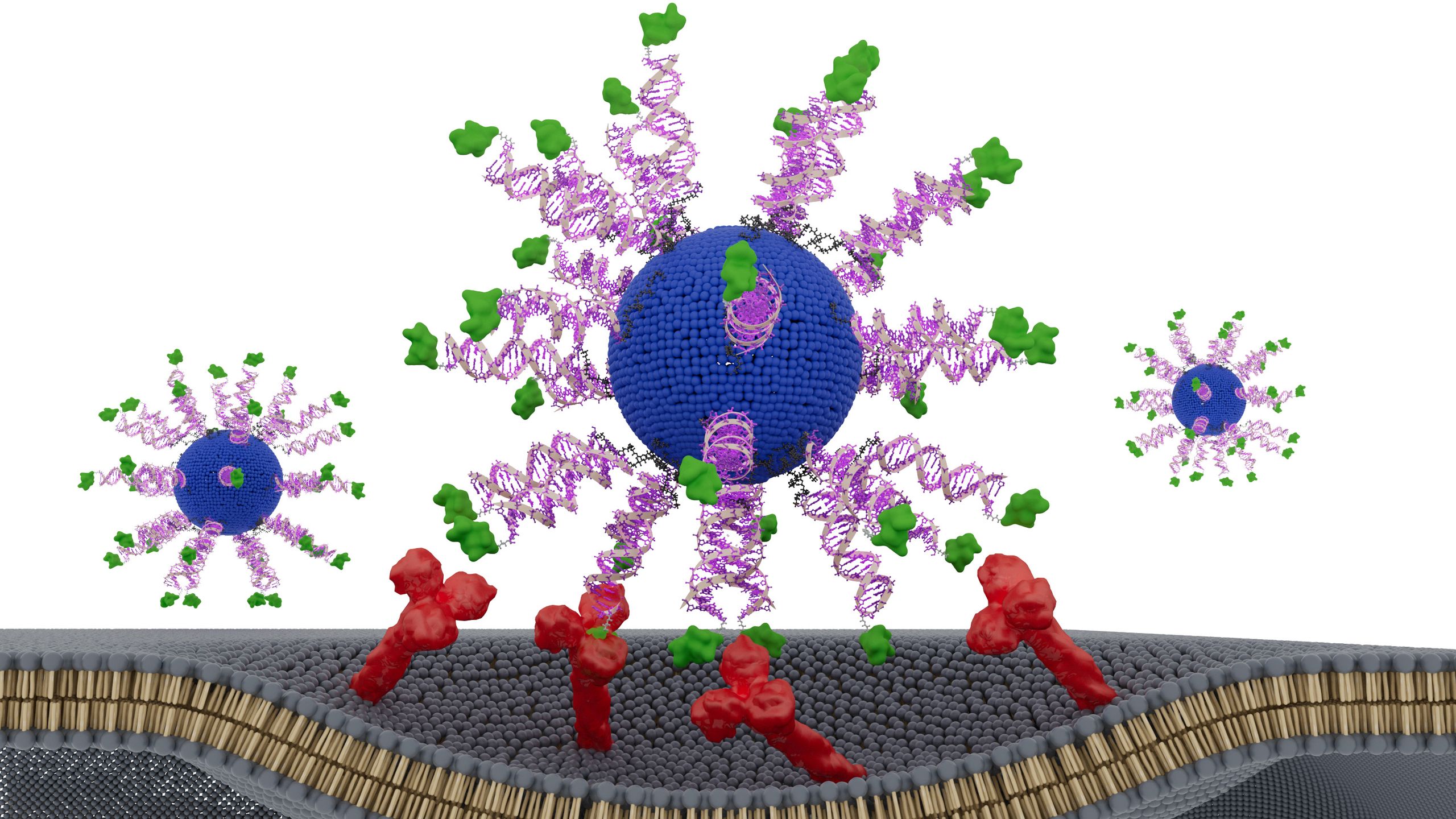

The vaccine uses spherical nucleic acids (SNAs) — globe-shaped DNA particles that enter immune cells and bind to targets more effectively than linear DNA does. Each SNA nanoparticle within the vaccine consists of a fatty core surrounded by an adjuvant and a fragment of an HPV protein from the tumor cells. The adjuvant mimics bacterial DNA and is recognized by the immune system as “foreign.”

The researchers tested three designs, changing only how the HPV fragment was positioned. One version hid it inside the nanoparticle, while the other two versions had the HPV fragment on the surface of the particle, attached at different ends of the fragment’s structure, known as the N terminus and the C terminus.

The version with the fragment attached to the surface via its N terminus triggered the strongest immune response, the team found. This design led killer T cells — immune cells that destroy infected, damaged and cancerous cells — to produce up to eight times more interferon-gamma, a key antitumor signaling protein. This made them more effective at killing HPV-positive cancer cells.

In mouse models of HPV-positive cancer, the vaccine significantly slowed tumor growth. Additionally, when tested in tumor samples collected from HPV-positive cancer patients, the N-terminus vaccine killed two to three times more cancer cells compared with the other two vaccine designs.

“This effect did not come from adding new ingredients or increasing the dose. It came from presenting the same components in a smarter way,” study co-author Dr. Jochen Lorch, the medical oncology director of the Northwestern Medicine Head and Neck Cancer Program, said in a statement.

“The immune system is sensitive to the geometry of molecules,” he said. “By optimizing how we attach the antigen to the SNA, the immune cells processed it more efficiently.”

Looking ahead, study co-author Chad Mirkin, inventor of SNAs and director of Northwestern’s International Institute for Nanotechnology, hopes this approach could help scientists redesign older vaccines that initially seemed promising but failed.

“This approach is poised to change the way we formulate vaccines,” Mirkin said in the statement. “We may have passed up perfectly acceptable vaccine components simply because they were in the wrong configurations. We can go back to those and restructure and transform them into potent medicines.”

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Hwang, J. et al. (2026). E711-19 placement and orientation dictate CD8+ T cell response in structurally defined spherical nucleic acid vaccines. Science Advances, 12(7). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aec3876