A mysterious volcanic comet has transformed into a giant, “fossil-like” spiral of light after one of its most violent outbursts in years, new photos reveal. The stunning spectacle is a reminder of how puzzling this particular planetary remnant really is.

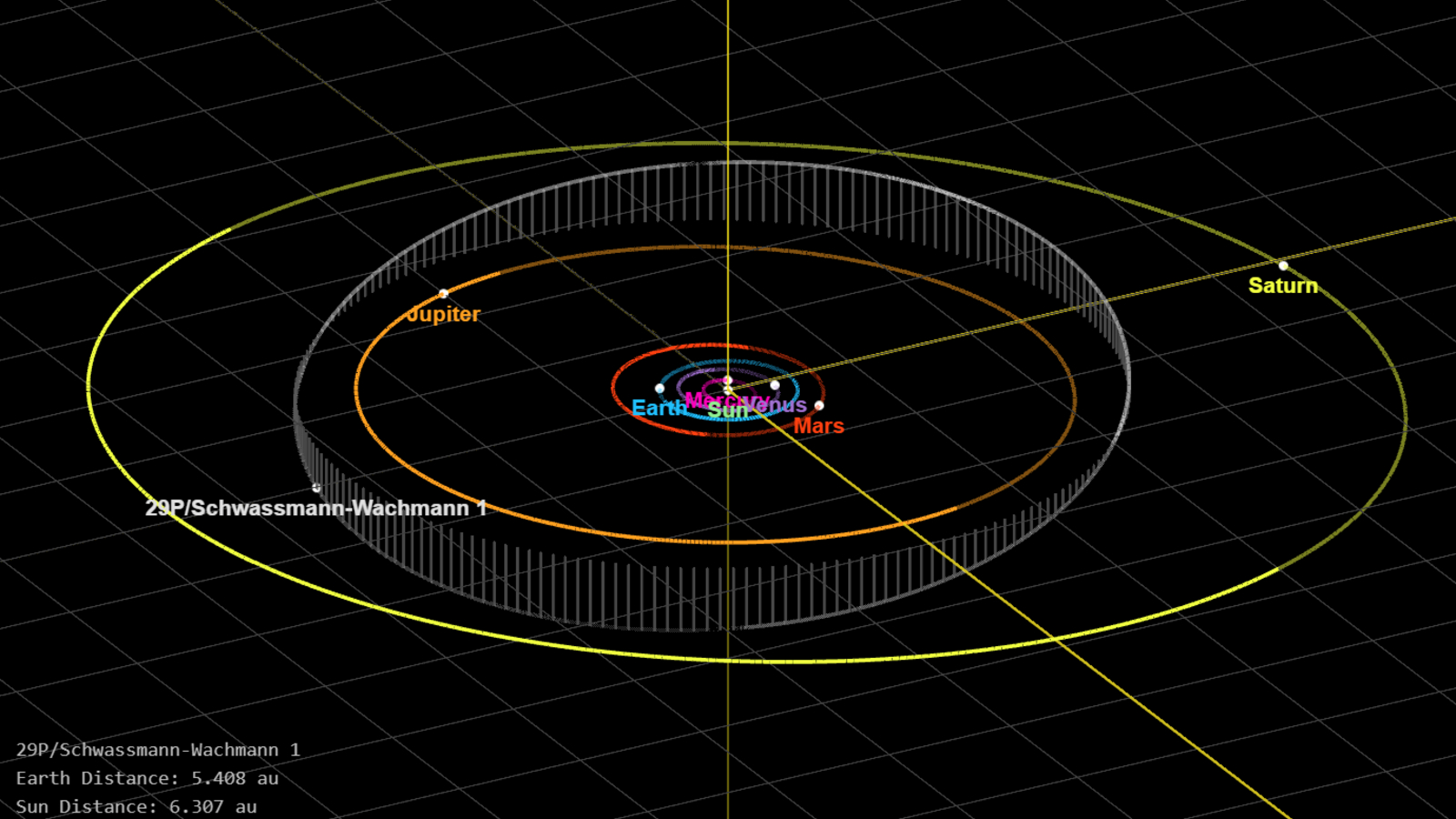

The unusual comet, known as 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann (29P), is a hefty ice ball spanning around 37 miles (60 kilometers) — roughly three times the length of Manhattan. It is part of a rare group of around 500 objects dubbed “cetaurs,” which spend their entire lives circling the inner solar system. The comet also belongs to an even more exclusive club known as cryovolcanic comets, which occasionally spew gas and ice across our cosmic neighborhood.

A cryovolcanic comet blows its top when its icy shell, or nucleus, soaks up too much solar radiation. This extra radiation superheats the mix of frozen gas and dust — called cryomagma — in the comet’s interior and causes the icy mix to sublimate. The resulting gas causes a pressure buildup in the comet’s center, which eventually forces open a crack in the nucleus, allowing it to spray its icy guts into space. When this happens, the fuzzy cloud of material surrounding the comet, known as its coma, expands significantly, allowing it to reflect more sunlight and making it shine much more brightly in the night sky.

On Feb. 10, Comet 29P experienced a sudden brightening event, roughly equivalent to a 100-fold increase in its luminosity, signaling that it had undergone a major eruptive event, according to Spaceweather.com.

This outburst is one of the comet’s “top five” eruptions of the past two and a half decades, experts told Spaceweather.com, and it’s the most powerful event since a quadruple eruption in October 2024, which caused Comet 29P to shine 300 times brighter than normal.

However, in the days following the explosive outburst, researchers began to notice something unusual about 29P’s expanding coma: The reflective cloud was not evenly distributed around the comet as it typically would be. Instead, the cloud appeared to have stretched out into a rare spiral shape.

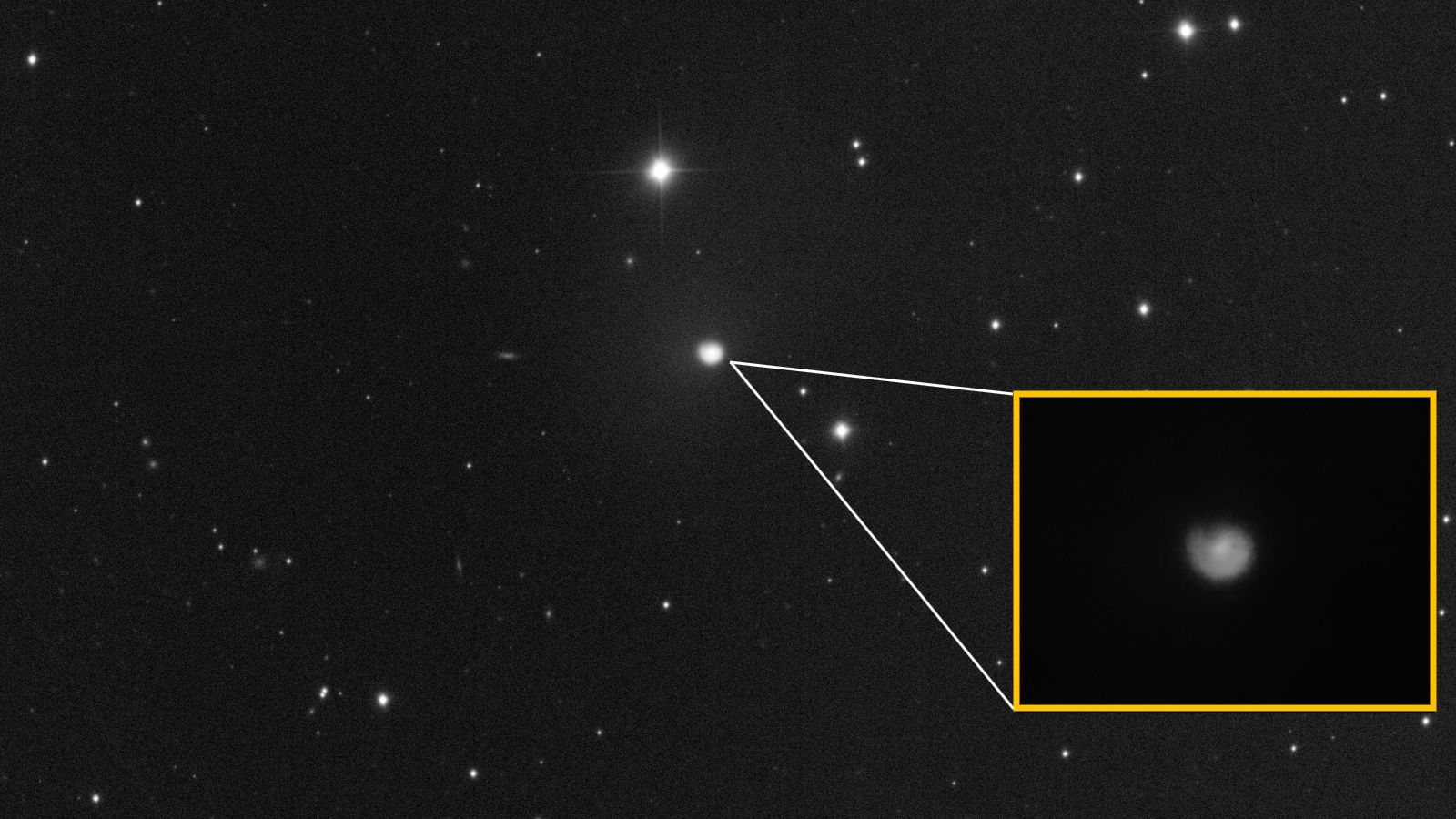

Amateur astronomer and astrophotographer Eliot Herman snapped the lopsided coma from the Rio Hurtado valley in Chile (see above) and said it resembled a fossil of an extinct shelled cephalopod known as an ammonoid. Fellow photographer Anthony Kroes, who also captured a stunning shot of the spiral from Wisconsin, remarked on its “snail-shell appearance.”

The unusual shape likely results from an internal rotation of the comet’s interior relative to its nucleus, which causes cryomagma to unevenly spew out of a newly formed vent on its icy surface, according to Spaceweather.com.

This is very similar to the “devil comet,” 12P/Pons-Brooks, which appeared to grow demonic horns during the initial eruptions of its solar flyby in late 2023, likely due to a notch on its surface that partially blocked the outflow of cryomagma, experts said at the time.

The interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, which made headlines as it zoomed through the inner solar system last year, also displayed evidence of cryovolcanism and likely leaked cryomagma through multiple jets.

Unexplained outbursts

Most cryovolcanic comets, like 12P/Pons-Brooks and the recently discovered Comet SWAN, are long-period comets that dwell in the outer solar system and drift toward the sun every few hundred or thousand years. They erupt only as they near our home star — and soak up additional radiation — before ceasing activity and quietly returning to the edge of our cosmic neighborhood.

However, Comet 29P orbits the sun in a roughly circular trajectory, meaning it’s pretty much always the same distance from the sun. It is located between Jupiter and Saturn — around six times farther from our home star than Earth is — so it does not receive much sunlight.

Still, Comet 29P experiences an average of 20 eruptions per year. Most of these are small, but occasionally, a much bigger outburst — like the one we have just seen — comes along, releasing up to 1 million tons of cryomagma into space.

This has been frustrating for researchers because they have no clear idea of what triggers these larger outbursts, when the comet’s conditions appear to remain fairly stable.

In April 2023, researchers predicted one of these major eruptions in advance, thanks to a mini dimming event just before the comet blew its top. However, they were still unsure why it happened.

How to see 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann

Comet 29P has passed its peak brightness. However, it has remained unusually luminous thanks to a second, smaller outburst Sunday (Feb. 15), which pumped a fresh batch of cryomagma into the comet’s coma, according to Spaceweather.com. (It is currently unclear if the reinvigorated coma will also expand into a spiral.)

You should still be able to see the comet with a decent telescope or pair of stargazing binoculars. It is currently located in the constellation Leo, according to TheSkyLive.com.

Major eruptions like this are often followed by multiple smaller eruptions, or “aftershocks,” meaning we could see more outbursts in the coming days or weeks, Richard Miles, an astronomer with the British Astronomical Association who has studied Comet 29P, told Spaceweather.com.

If you decide to head out under the stars, you may also want to keep an eye out for Comet C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś), which is shining brightly after passing its closest point to Earth on Tuesday (Feb. 17). Researchers predict that this ice ball may soon be kicked out of the solar system forever, similar to 3I/ATLAS, so this may be your only chance to see it.

In April, we will be treated to two more exciting comets: the newly discovered “sungrazer” comet C/2026 A1 (MAPS), which could shine bright enough to be seen with the naked eye during the daytime, and the long-period comet C/2025 R3 (PanSTARRS), which could also become visible without a telescope at night.