A sea raiders’ boat that sank off the coast of Denmark 2,400 years ago has been hiding a fingerprint, as well as several chemical clues that are now helping researchers uncover just where these raiders came from millennia ago, a new study finds.

The vessel, known as the Hjortspring boat, is the oldest known wooden plank boat in Scandinavia, and is currently on display at the National Museum of Denmark. But its origins have long been an enigma.

About 2,400 years ago, about 80 sea raiders on an armada including this boat and three others attacked the island of Als, off the coast of what is now Denmark. But the raiders lost. In giving thanks for their victory, the people on Als sank the boat as an offering along with the attackers’ weapons and shields.

The sinking of the boat in the fourth century B.C. helped preserve it over the centuries, as water is a low-oxygen environment. After its discovery in the 1880s, the boat was later excavated from the bog of Hjortspring Mose in the 1920s (earning the ship its name).

“But at the time, we lacked the modern scientific methods that we needed to answer the mystery of where these attackers came from,” Fauvelle said in a video about the research.

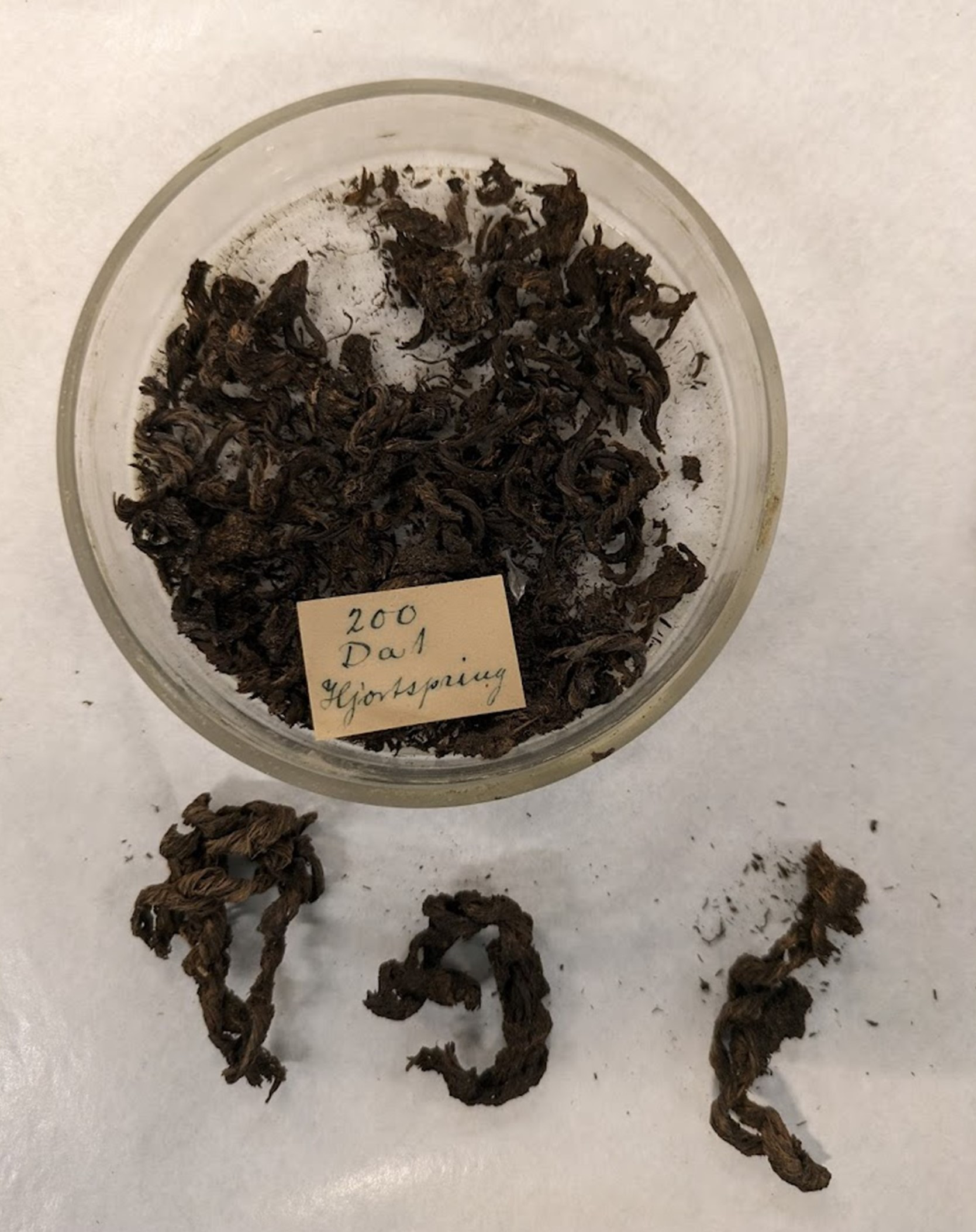

Recently, the researchers decided to take a fresh look at the boat. Before it was put on display in the museum, the boat had been chemically preserved. So, the team sifted through archives and old records in multiple museums in an effort to uncover parts of the boat that had been left untouched.

Finally, they found several fragments of caulking tar and rope, including a piece of tar that had the ancient fingerprint of someone who likely helped repair the vessel, a finding that Fauvelle called “really fantastic.”

“This remarkable fingerprint provides a direct link to the ancient seafarers who used this boat,” the researchers wrote in the study, which was published on Dec. 10 in the Journal PLOS One.

To study the caulking tar, the researchers used gas chromatography and mass spectrometry, techniques that examine the chemical makeup of samples. They found that the waterproof tar was a mixture of animal fat (likely tallow) and pine pitch, a sticky and stretchy substance also known as resin.

“This suggests the boat was built somewhere with abundant pine forests,” Fauvelle said in the statement.

The new finding throws cold water on an old idea that the boat originated near modern-day Hamburg, Germany, as previous analyses had found that the vessel carried wood containers that looked like ceramics from the Hamburg region. It now appears that the boat may have come from much farther away in the Baltic Sea region, which has pine forests.

“Pine forests only existed in certain parts of northern Europe at this time,” Fauvelle said in the video, adding “we suggest that they came from somewhere along the coast of the Baltic to the east of the modern day island of Rügen [in Germany].”

If this idea is accurate, it suggests that the attackers sailed a great distance over open sea for the raid, Fauvelle said.

Researchers also used carbon dating to study rope from the boat. Analyzing the lime bast cordage, which comes from the inner bark of trees, the team confirmed the boat’s previously determined timeline of between 400 B.C. and 101 B.C., which falls in the pre-Roman Iron Age of Scandinavia. The researchers carbon dated the boat to between 381 and 161 B.C., which is the first direct date from the boat’s material. The researchers also worked with rope makers to create replicas of the cordage and study the rope-making process.

Using X-ray tomography to scan the caulking and cordage in sections, the team made digital 3D models, which enabled them to study the fingerprint. Analyzing the print’s ridges didn’t narrow down the sex or identity of who made the print, however.

Going forward, Fauvelle hopes to extract human DNA from the tar to learn more about the people who made and used the boat. Understanding faraway raids such as this one could help explain ancient maritime warfare and Iron Age trading systems.

Watch On