This past year was an exciting one for archaeology, with scientists using cutting-edge technology to learn about humans and our close extinct relatives.

The array of tools available to archaeologists is impressive. One is lidar (light detection and ranging), which involves shooting lasers from an aircraft to map the ground’s topography, which was used to discover ancient settlements hidden deep in the Amazon rainforest in January. Meanwhile scientists studying a Neanderthal’s crushed remains in Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan analyzed the proteins in the deceased’s tooth enamel and found that she was female, which helped experts create a facial reconstruction of her.

Another technique that yielded a treasure trove of new information this year is ancient DNA analysis, which can show how humans are related to one another and which features they had. For an ice age baby boy in Europe, DNA revealed he had a somewhat common appearance at that time — blue eyes, dark skin and curly dark-brown to almost black hair, a September study found.

Even plain old metal detecting — often by amateurs — revealed stunning finds, including the discovery of a silver hoard from the Viking Age, 300-year-old coins hidden by a Polish con man and Roman cavalry riding gear.

However, a few stories stand out above the rest. Here are my top picks for 2024.

“An offering to energize the fields”

Our coverage of mass child sacrifice in a pre-Incan culture in Peru was the most read archaeology story on Live Science in 2024. This child sacrifice site is actually one of many found in Peru from the Chimú culture, which thrived in the region from the 12th to 15th centuries and is well known for its textiles and art. In previous coverage of a similar sacrificial site, an archaeologist told Live Science that the Chimú viewed death, people’s roles in life and even the cosmos differently. It’s possible that the Chimú saw sacrifice as the only way to save their culture from destruction.

Related: 32 stunning centuries-old hoards unearthed by metal detectorists

An isotopic analysis of this newfound 700-year-old sacrifice gives us hints about the sacrificed children. Researchers looked at the isotopes within some of the victims. Isotopes are variations of an element that have a different number of neutrons in their nuclei, and are consumed through food and drink, and can reveal where a person grew up. The analysis indicated that some of the children came from another culture that lived north of the Chimú, suggesting that at least a few of the victims had been captured by the Chimú.

An 18,000-year-old lineage

Scientists have long grappled with how long ago the first Americans reached North and South America. The question isn’t settled yet, but strong evidence goes back as far as 23,000 years in New Mexico.

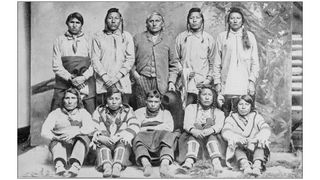

Even with that datapoint, it’s nice to have other evidence that tells us about America’s early inhabitants. This includes the Blackfoot Confederacy, Indigenous peoples now living in the Great Plains of Montana and southern Alberta. In April, researchers — including three lead Blackfoot authors — used ancient DNA samples and statistical modeling to learn that their lineage goes back 18,000 years. Put another way, the Blackfoot Confederacy can trace their origins back to the last ice age, which didn’t end until 11,700 years ago.

There are now a multitude of studies looking at ancient DNA, but many of them are from individuals in Europe, including from the victims of Mount Vesuvius in Pompeii, early Celtic elites in Germany and hunter-gatherers and farmers in prehistoric Denmark. There aren’t as many ancient DNA analyses of people from the Americas simply because we haven’t found as many ancient human remains. But this study Blackfoot Confederacy is helping to fill that gap.

One of the last Neanderthals

Much remains a mystery about the Neanderthals’ demise roughly 40,000 years ago. But a DNA analysis of a Neanderthal known as Thorin, nicknamed after a dwarf in “The Hobbit” by J. R. R. Tolkien, gave us some wild gossip about his group.

Thorin hailed from a previously unknown Neanderthal lineage that had been genetically isolated for the past 50,000 years, even though they were only a few days’ walk from another group of Neanderthals, the researchers found. He was also highly inbred, which is perhaps unsurprising given his group’s isolation. Thorin lived around 42,000 years ago, meaning he was one of the last Neanderthals. It makes you wonder how unconnected other Neanderthal groups were to each other, and how connected they were to humans.

Modern human and Neanderthals mated during a 7,000-year-long “pulse”

Finally, genetics can reveal when modern humans interacted with Neanderthals, at least somewhat. Two studies that used different genetic methods both found that starting around 49,000 years ago, modern humans and Neanderthals mated for a 7,000-year-long “pulse” lasting generations. It’s unclear why they started and why they stopped. And we’ll likely never know if this mingling was consensual or what Neanderthal-human relationships looked like. But at least we know this much: within a few thousands of years of their extinction, Neanderthals mixed with humans, leaving their genetic imprints on our genomes even to this day.