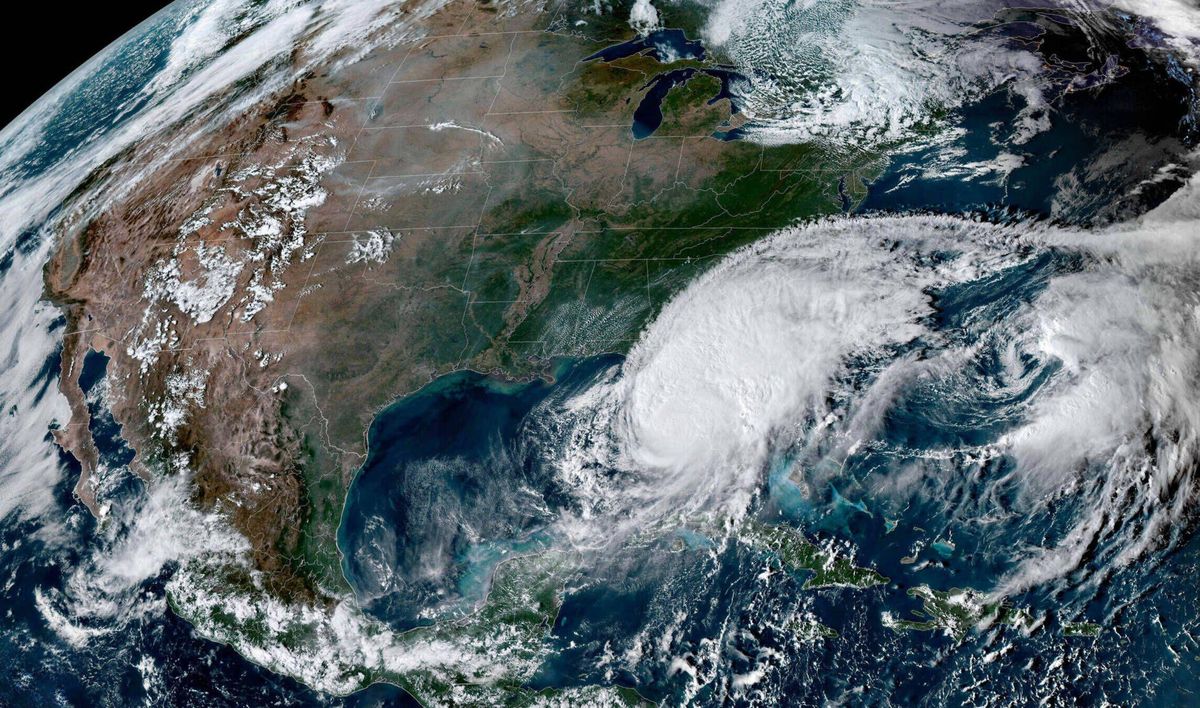

Hurricane Milton smashed into Florida’s west coast on Wednesday night (Oct. 9), spawning multiple tornadoes and 28-foot-high (8.5 meters) waves as it plowed a deadly path across the state.

Streets turned into rivers as the hurricane made landfall near Siesta Key in Sarasota County, according to the National Hurricane Center (NHC). It arrived as a Category 3 storm, bringing 120 mph (190 km/h) winds and storm surges of up to 13 feet (4 m), before weakening to a Category 1 as it crossed central Florida.

Milton, which battered Florida just a few weeks after Hurricane Helene, seemed to come out of nowhere, intensifying rapidly from a tropical depression to a Category 5 over the space of 2 days.

“Major storms developing sequentially isn’t all that unusual. What is almost unprecedented is two major hurricanes targeting the same state within two weeks,” Ryan Truchelut, chief meteorologist and co-founder of the weather-tracking website WeatherTiger, told Live Science. “This is the fastest turnaround time for two major hurricane landfalls in Florida history.”

In recent decades, enhanced satellite imagery and more detailed models have vastly improved how far out meteorologists can forecast devastating storms — buying precious time for evacuations. But climate change could make early warnings tougher as back-to-back, rapidly intensifying, storms become more common.

Related: How strong can hurricanes get?

Hurricanes are fueled by a thin layer of evaporating warm ocean water that rises to form storm clouds. The warmer the ocean is, the more energy the system gets, accelerating the formation process so that violent storms can rapidly take shape. This is why hurricane season occurs from June to November and why the most powerful storms in the Atlantic usually occur between August and September, when ocean temperatures peak.

Climate change has caused ocean temperatures to soar. Since March 2023, average sea surface temperatures around the world have hit record-shattering highs. This has made extremely active Atlantic hurricane seasons much more likely than they were in the 1980s.

These warming waters have also made rapidly intensifying storms like Milton more than twice as likely, according to a 2023 study.

Rapid intensification is when a storm’s sustained wind speeds increase by at least 35 mph (56 km/h) in a 24-hour period, according to the NHC.

“Hurricane Milton has obliterated that minimum, undergoing extreme, rapid intensification,” Brian Buma, a senior climate scientist at the nonprofit Environmental Defense Fund, told Live Science. “Its maximum sustained wind speed increased by 90 mph [145 km/h] in roughly 25 hours. Rapid intensification appears to [be] becoming more common across basins.”

The speed of Milton’s intensification means it is tied with hurricanes Wilma, in 2005, and Felix, in 2007, for the fastest time on record for an Atlantic storm reaching Category 5 intensity, said Philip Klotzbach, a research scientist in the department of atmospheric science at Colorado State University.

“Milton also intensified by 80 kt [90 mph] in 24 hours,” Klotzbach told Live Science. “That’s the most intensification for a Gulf of Mexico storm in a 24-hr period on record.”

The record-breaking rate of strenghtening means meteorologists and emergency planners have a smaller window to predict life-threatening storms and warn residents to evacuate.

The increased threat has led some scientists to suggest changing the Saffir-Simpson scale, which categorizes storms from one to five based upon their wind speeds, to include even more powerful Category 6 storms.

“Milton is the storm that we were envisioning in our paper,” Michael Wehner, a climate scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, told Live Science. “The most intense hurricanes are more intense in the past decade or so than in the rest of the historical record because of climate change. Changing the scale would raise awareness of that unfortunate reality.”

Wehner argued that the current scale “is inadequate to convey all of the danger of an impending storm.” Most of the threat from hurricanes does not come from winds, he said, but from water coming from storm surges and rainfall.

“The human tragedies of Helene and Milton are immense,” Wehner added. “Both of these storms would have been large and devastating without climate change. However, climate change has exacerbated this suffering.”