Earthquakes that jiggle Earth’s middle layer may be more widespread than scientists thought.

A new map of these mysterious deep earthquakes shows that they occur all around the world and that they may have a variety of causes. That’s interesting, said study senior author Simon Klemperer, a geophysicist at Stanford University, because mantle earthquakes were once thought to be impossible, or at least rare. These quakes originate below a border known as the Mohorovičić discontinuity, or “Moho” — the line between the brittle crust and the hotter, gooier mantle.

Most earthquakes start in the crust, which is like a layer of toasted sugar over the softer, more deformable cream filling that is the mantle. This brittle crust can’t deform, so it cracks under stress, causing the ground to shift and shake. For a long time, geoscientists thought this couldn’t happen in the mantle, which has a taffy-like texture and tends to ooze instead of snap. But over the years, seismologists studying earthquakes have turned up evidence of quakes with deep origin points more than 22 miles (35 kilometers) down, which would put them below the Moho.

But pinpointing these quakes is difficult, especially when they are not large. In general, these earthquakes are so deep that they can’t be felt at the surface, regardless of their size. The Moho’s depth also varies from place to place, so it’s possible that some very deep quakes are still in the crust.

Traditional methods of pinpointing mantle quakes required a specific understanding of how thick the crust might be in that particular location. But Klemperer and his co-author, Stanford doctoral student Shiqi Wang, developed a method that uses specific types of earthquake shear waves that tend to get trapped in either the crust or the mantle. The pattern of these waves in each individual earthquake can determine whether it’s likely to have started above or below the Moho.

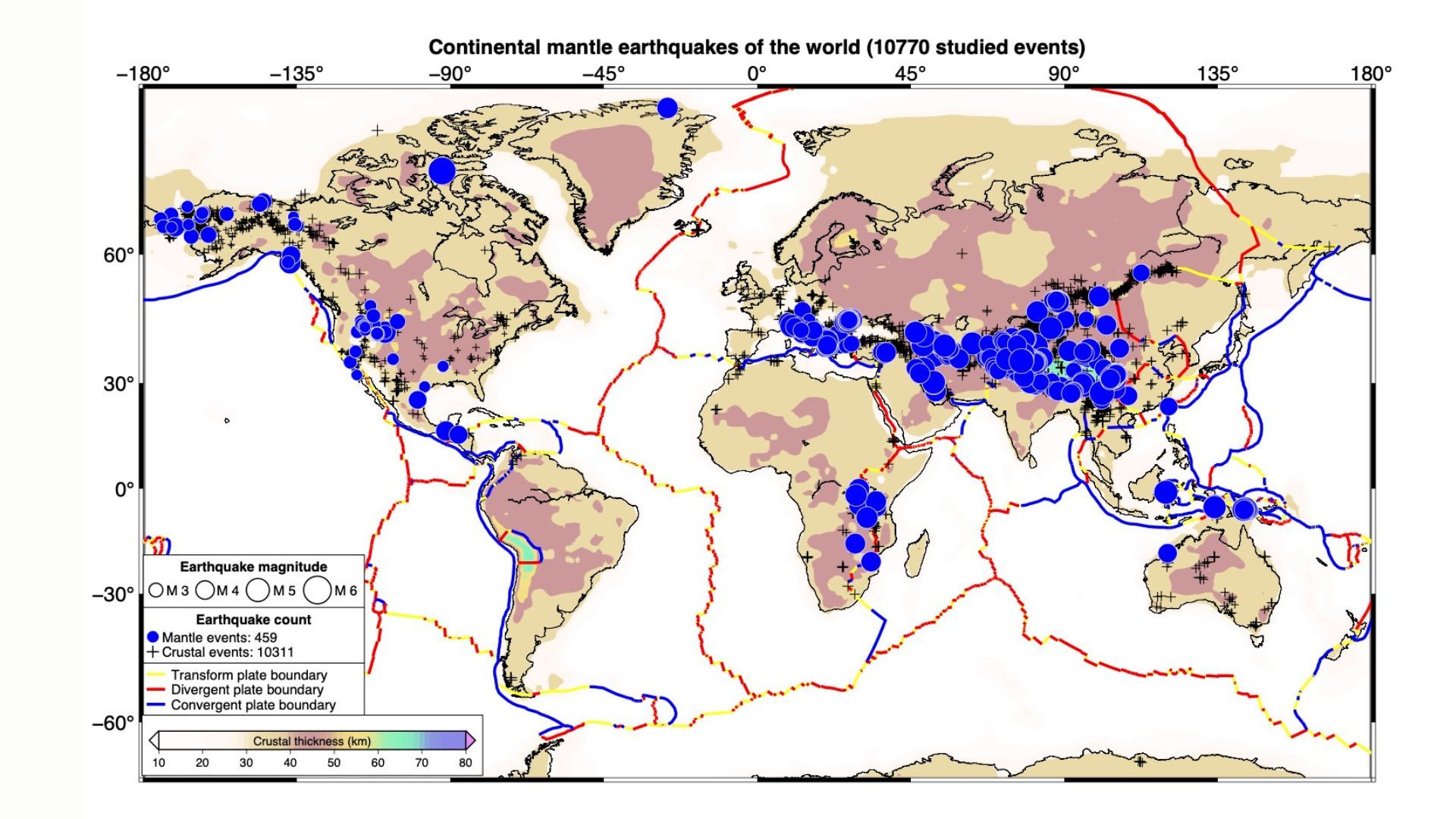

First, they tested the method in Tibet in 2021. Now, in a new paper published Feb. 5 in the journal Science, they have taken the research global. The researchers excluded subduction zones, which often have deep earthquakes because rocks from the crust get pushed into the mantle in these regions. Instead, the team focused on the more elusive phenomenon of mantle earthquakes under the continents.

They found mantle quakes all over the place. A dense band of them stretches from the Alps to the Himalayas, probably related to the mountain-building continental collisions in these regions. Another cluster occurs in East Africa, where the continental crust is rifting apart. There are also mantle earthquakes under the western United States and in Baffin Bay, Canada, the researchers found.

Some of the cluster locations were surprising. “There were some regions where nobody had found these before, like in the Bering Sea,” Vera Schulte-Pelkum, a geologist at the University of Colorado Boulder who was not involved in the study, told Live Science. “I’d love to get an interactive version of these and zoom around.”

The global overview should allow other scientists to do more specific studies on individual mantle quakes, Klemperer said, and perhaps better pinpoint their depths and the mechanisms driving the earthquakes.

“It’s tremendously exciting that we have this tool that can now be applied on a very routine basis,” he said.