A shock wave, far away in space, might be the telltale sign of the first confirmed “runaway” supermassive black hole, escaping its host galaxy at 2.2 million miles per hour (3.6 million km/h).

The potential confirmation by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), published on the preprint server Arxiv on Dec. 3, has not yet been peer-reviewed. But it has been submitted to Astrophysical Journal Letters and lead study author Pieter van Dokkum, a professor of astronomy and physics at Yale University, has published several peer-reviewed papers about candidate supermassive black holes in recent years.

Tracing a stream of stars

The candidate black hole was first spotted back in 2023 by van Dokkum’s team, who saw a faint line in an archival Hubble Space Telescope image. The sight was so strange that the team followed up with fresh observations from the Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

Observations back then showed that the black hole has a mass of 20 million suns, and that the strange line was a “wake” of young stars stretching 200,000 light-years across space — twice the diameter of the entire Milky Way. The Hubble image captures a moment in time when the universe was roughly half its current age of 13.8 billion years.

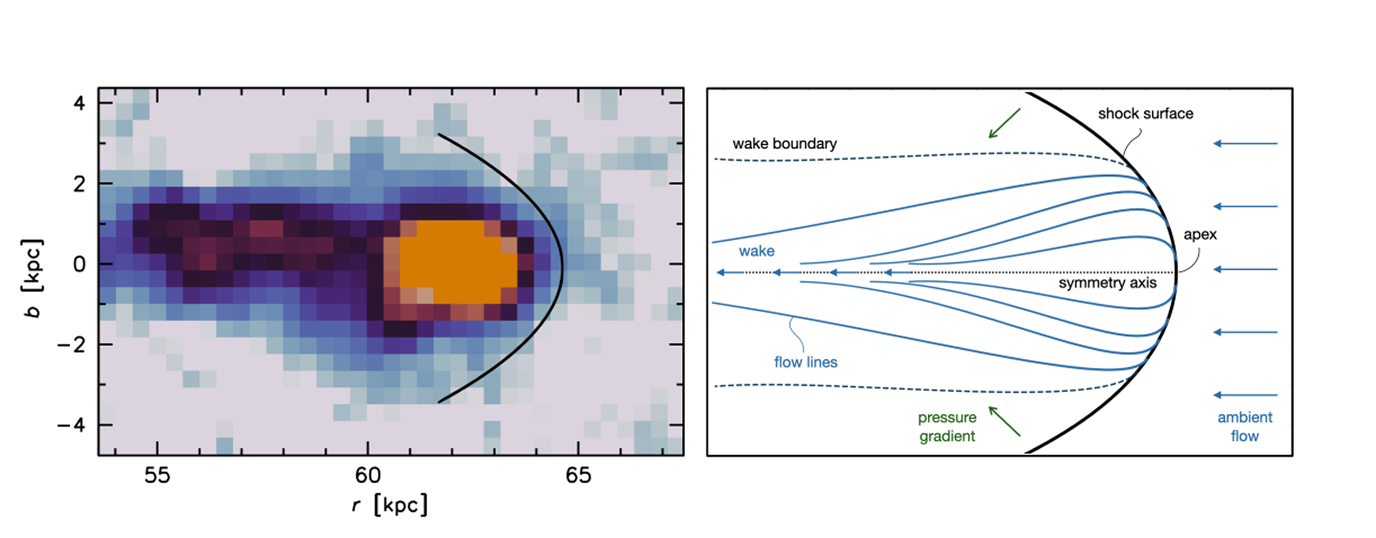

“We suspected that this strange object might be a runaway supermassive black hole, but we did not have ‘smoking gun’ proof,” van Dokkum said. So, for their new research, the team turned to JWST, a deep-space observatory that is unique in its “sensitivity and sharpness,” van Dokkum said, “to see the bow shock that is created by the speeding black hole.”

The resulting imagery astounded the team.

JWST’s mid-infrared instrument rendered the shockwave, or bow shock, at the leading edge of the candidate black hole’s escape with unprecedented clarity. “It’s a bit like the waves created by a ship,” van Dokkum said. “In this case, the ship is a black hole and very difficult to see, but we can see the ‘water’ — really, hydrogen and oxygen gas — that [the black hole] pushes out in front of it.”

Van Dokkum was astonished. “Everything about this object told us it was something really special, but seeing this clear signature in the data was incredibly satisfying,” he added.

Aside from JWST’s sheer resolution, van Dokkum said his study showed that the observations matched Hubble’s and Keck’s data in different wavelengths of light. The data “all provide different pieces of the puzzle,” he said, “and they fit together beautifully — exactly as predicted by theoretical models.”

A supermassive mystery

Studying runaway black holes, like this candidate one, shows scientists more about how galaxies and black holes evolved, van Dokkum said. Most large galaxies have supermassive black holes embedded in their center, including our own Milky Way. Whether they can escape their tight galactic bonds is a longstanding mystery.

The only way that a supermassive black hole could be ripped out of its galaxy, according to van Dokkum, is if at least two of these black holes got extraordinarily close to each other, with the intense gravitational interaction “kicking” one out of place.

The new research suggests the candidate runaway was produced after at least two, and potentially as many as three, black holes all interacted. With masses of at least 10 million suns each, van Dokkum said the violence of the encounter must have been “quite something.”

As for where to look next for a runaway supermassive black hole, the research paper notes “several promising candidates,” but the interpretation of these systems is difficult. One example is the ambiguous object known as the “Cosmic Owl,” which is roughly 11 billion light-years away from Earth.

The Cosmic Owl, according to the new paper, includes two galactic nuclei — each with an active supermassive black hole at the galaxy’s heart — and a third supermassive black hole that is, oddly, “embedded in a gas cloud” between the two galaxies.

How that third black hole arrived in a gas cloud is a matter of dispute. Some researchers say the black hole may be a runaway that escaped from one of the host galaxies, but JWST observations by van Dokkum’s group challenge that interpretation. Their observations suggest the out-of-place black hole “more likely … formed in-situ through a direct collapse” of gas, produced by shockwaves after the two galaxies nearly collided with one another.

Further study is needed on this, and other objects that may contain possible black hole runaways. Van Dokkum cited the current Euclid and forthcoming Nancy Grace Roman space telescopes as promising survey instruments, since these telescopes are designed to look at the whole sky, unlike JWST. “That will tell us how often this happens — something we’d dearly like to know.”