Jupiter’s ice-covered moon Europa appears to have life-friendly molecules on its surface.

Al Emran, a researcher with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, spotted ammonia on the surface of Europa while looking through old data from the Galileo mission, which studied Jupiter and its moons from 1995 to 2003.

It is the “first such detection at Europa” and therefore has important implications for the habitability of the icy moon, which is considered one of the most likely places in the solar system to host extraterrestrial life, according to the statement.

Alien ice moon

Ammonia is a nitrogen-bearing molecule and one of the ingredients of life as we know it, alongside carbon, hydrogen, oxygen and water. In the new paper, Emran said the finding was therefore of “astrobiological significance, given nitrogen’s essential role in the chemistry of life.”

Brandon Specktor

Europa is the fourth-largest of Jupiter’s 95 known moons, measuring about 90% the size of Earth’s moon. Studies of Jupiter’s magnetic field suggest that Europa contains a deep layer of electrically conductive fluid, which scientists suspect is most likely a vast, salty ocean trapped beneath the moon’s icy crust. This hidden ocean makes Europa a prime contender for extraterrestrial life in our solar system — though more up-close observations are needed to test this hypothesis.

The Galileo spacecraft worked in the Jupiter system between 1995 and 2003, before it ran low on fuel. Engineers deliberately steered the spacecraft into the giant planet to avoid any risk of contaminating Europa or other icy moons. Although the mission concluded operations more than 20 years ago, scientists sometimes find new insights in older datasets, either by using newer tools or knowledge, or by examining information that was not previously scrutinized.

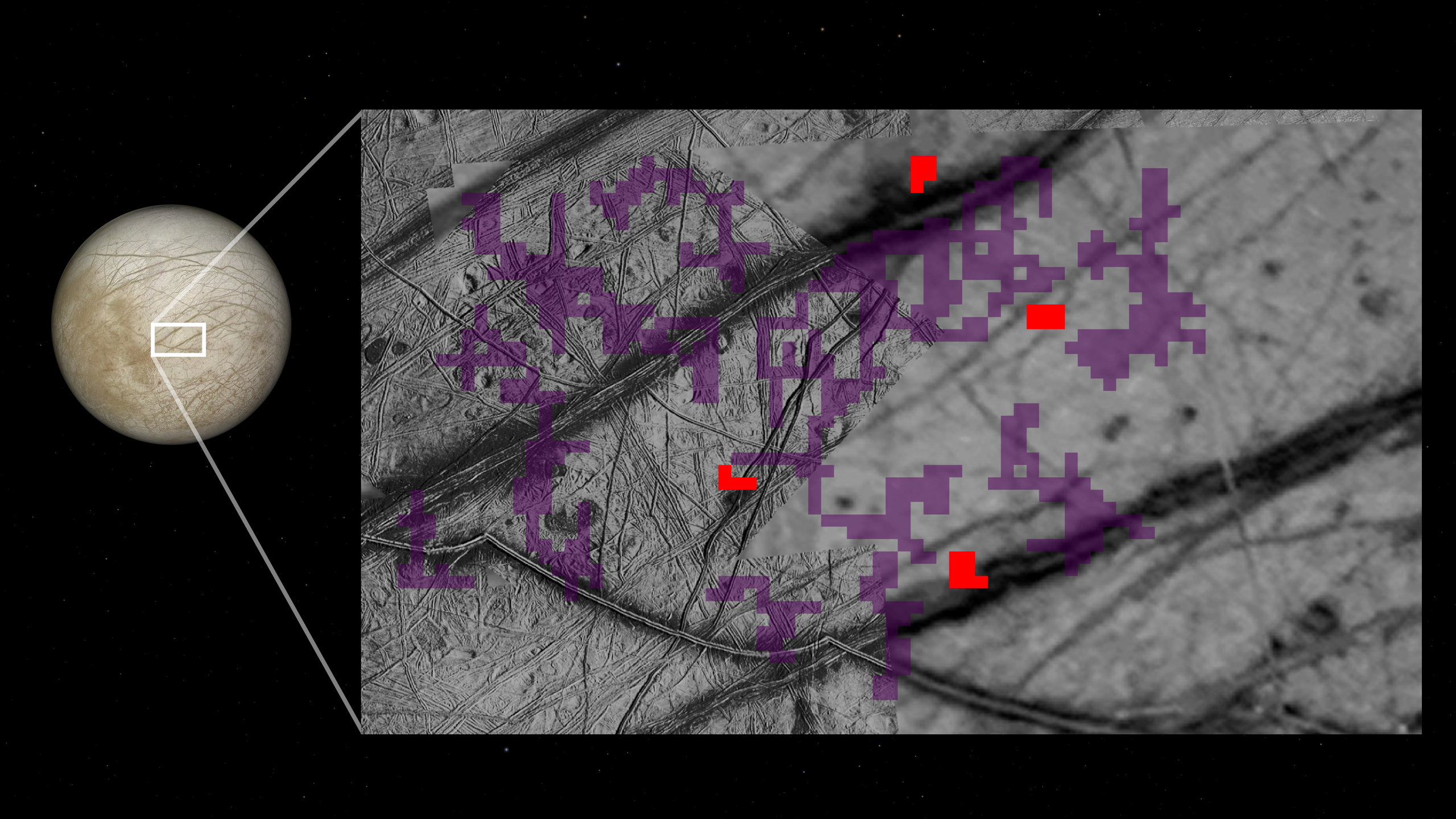

In the new research, NASA spotted traces of ammonia near fractures on the icy surface of Europa. It is believed that these fractures included liquid water with ammonia compounds; the ammonia lowers the freezing point of water, sort of like antifreeze, the agency said.

The ammonia may have come “from either the moon’s subsurface ocean, or its shallow subsurface,” NASA officials said in the statement. That’s because ammonia doesn’t last long in space because it gets broken down by ultraviolet light and cosmic radiation. Cryovolcanism, or icy volcanism, likely pushed the ammonia compounds to the surface, they explained.

A follow-up mission may reveal more insight: Europa Clipper, which launched in October 2024, is expected to arrive at the Jupiter system in April 2030. The mission will specifically look for chemical signs of habitability on the icy moon.