Roughly 4.5 million years ago, the sun passed remarkably close to two intensely bright stars whose radiation flooded nearby space — and the encounter left a ghostly scar that astronomers can still detect today, according to a new study.

The research team says the close pass helps to solve a decades-old mystery of why the space around our solar system is far more energized than models predict, including why it contains a surplus of ionized helium.

Today, the stars mark the front and rear legs of the constellation Canis Major (the Great Dog), more than 400 light-years from the solar system. But roughly 4.5 million years ago, when the stars brushed past the solar system, they were younger, hotter and brighter. Their passage also may have overlapped with the time when Lucy — a remarkably complete fossil of an early human ancestor discovered in Ethiopia in 1974 — walked the Earth.

“They weren’t headed straight toward us…but that’s close,” Shull told Live Science. “If Lucy and her friends had looked up and had noticed the stars, the two brightest stars in the sky would have been not Sirius, but Beta and Epsilon Canis Majoris.”

The findings were published Nov. 24 in The Astrophysical Journal.

A lingering mystery

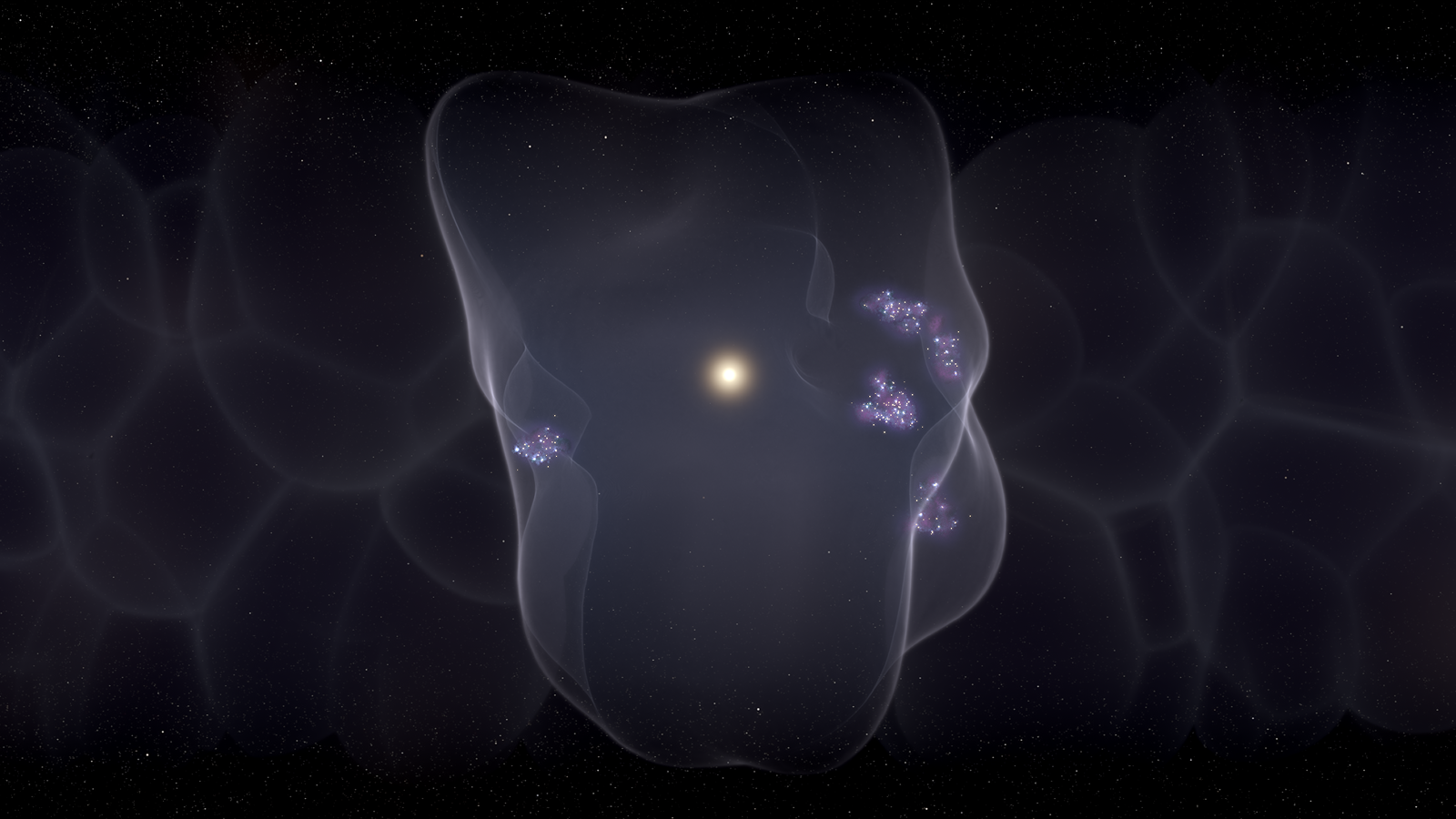

Today, the solar system drifts through a diffuse patchwork of more than a dozen nearby wisps of gas and dust called the local interstellar medium, made primarily of hydrogen and helium and extending roughly 30 light-years from the sun.

Astronomers think these clouds were sculpted over several million years by shock waves from exploding stars in the Scorpius-Ophiuchus region, a rich cluster of massive stars about 300 light-years from Earth, which compressed interstellar gas into the thin local clouds seen today.

Observations dating back to the 1990s, including from NASA’s now-retired Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer space telescope, revealed that this region is unusually ionized. Helium atoms, in particular, have been stripped of their electrons at nearly twice the rate expected relative to hydrogen.

That imbalance has puzzled astronomers, because helium requires more energetic radiation to ionize than hydrogen does. This makes its elevated ionization difficult to explain with the sun’s radiation alone, which does not extend that far beyond the solar system.

To investigate the mystery, Shull and his colleagues calculated the properties and ultraviolet output of Beta and Epsilon Canis Majoris, using measurements from the European Space Agency’s Hipparcos satellite, which mapped the positions of more than a million stars across a four-year mission that ended in 1993.

Knowing how far away the two stars are today — about 400 light-years — and how fast they are moving allowed the team to trace the stars’ paths backward through time to reconstruct their close pass by the solar system roughly 4.5 million years ago.

“It’s like a dance floor”

The team’s models show that the wispy local clouds would have been intensely ionized by the two stars’ radiation — at levels up to 100 times stronger than those seen today. Over time, the gas would have slowly returned to a more neutral state through a process called recombination, in which free electrons reattach to ions and become atoms.

“It’s like a dance floor,” Shull told Live Science. “You’ve got protons and electrons dancing around, and sometimes they’re dancing together and sometimes they’re popping apart.”

But that process takes time, and continued exposure to radiation from other sources continues to keep the gas partially ionized, Shull said. Astronomers had previously identified other sources of ionizing radiation, including three nearby white dwarf stars — G191-B2B, Feige 24 and HZ 43A — compact stellar remnants that are known to emit strong ultraviolet light. Researchers also pointed to the Local Bubble — a vast, supernova-blown region of hot gas that extends about 1,000 light-years around the solar system.

“More energetic photons preferentially ionized helium,” he said. “That’s the bottom line.”

The pieces come together

Although astronomers have had reliable stellar motion data for decades, Shull said the problem became solvable only recently. Advances in ultraviolet and X-ray observations made possible by suborbital rocket flights, along with improved models of stellar evolution and atmospheres — and the computing power needed to run them — finally allowed researchers to connect the dots.

“The problem was ripe in the sense that all the pieces of the puzzle of the mystery were starting to come together,” Shull said.

The findings also may have implications closer to home. The local clouds help shield the planet from high-energy particles that roam the galaxy and that scientists suspect could erode Earth’s ozone layer.

The sun, however, is not expected to remain inside these clouds indefinitely. As it drifts onward through the galaxy, researchers estimate it could exit the protective region in as few as 2,000 to a few tens of thousands of years. “Then, we’re going to be in for a big dose of radiation,” Shull said.

Looking ahead, Shull said that understanding how atoms in the wispy local clouds shifted between more charged and more neutral states as radiation waxed and waned while the two stars approached, passed by and moved away from our solar system remains part of a larger puzzle researchers are still assembling. “The problem isn’t completely solved,” Shull said, “but I think we have the right track.”