A striking “green comet” about the size of a small city is lighting up the night sky as it nears Earth next week. Experts predict the hefty iceball may soon be permanently ejected from the solar system, dooming it to drift through interstellar space — like the “alien” comet 3I/ATLAS.

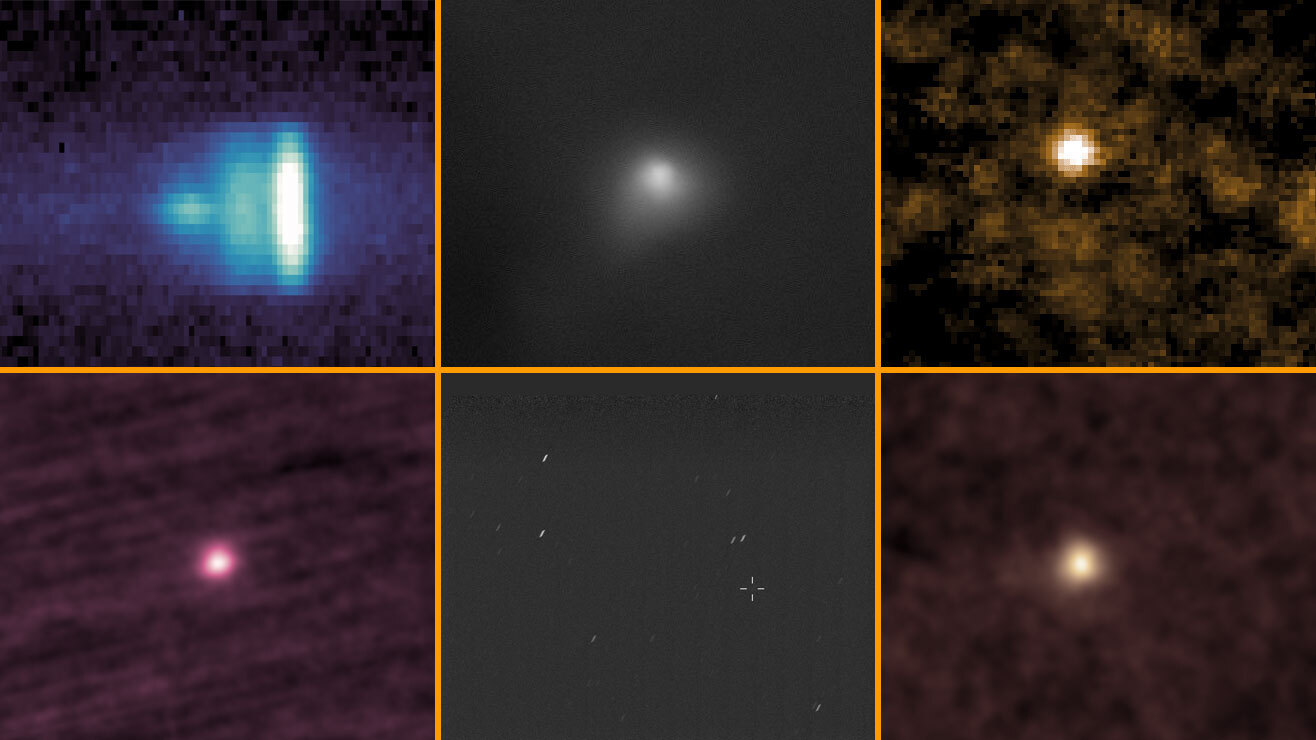

The new comet, dubbed C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś), was discovered in March 2024 by Polish astronomer Kacper Wierzchoś, who spotted the icy object sailing toward us with a 4.9-foot (1.5 meter) telescope at the Mount Lemmon Observatory in Arizona. The comet has since been observed by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), which detected large amounts of carbon dioxide in its coma — the cloud of gas and dust that surrounds the comet’s icy shell.

An initial analysis of JWST data suggested that Comet Wierzchoś’ nucleus has a diameter of around 8.5 miles (13.7 kilometers), which is roughly two-thirds the length of Manhattan and around four times the island’s width. However, a more recent study, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, hints that this may be an overestimate.

Comet Wierzchoś originates from the Oort cloud — the expansive reservoir of comets and other icy objects lurking near the outer edge of the solar system — and is hyperbolic, meaning that it has an open and flattened trajectory, and does not repeatedly orbit the sun. This is likely the first time it has ever ventured into the inner solar system, the researchers suspect.

Some researchers believe that it has been slowly falling toward the sun for between 1 million and 3 million years, although it is hard to tell for sure. But most experts agree that the gravitational kick from its current solar slingshot will fire it out of our cosmic neighborhood forever and into interstellar space, according to Spaceweather.com.

The eccentric iceball recently passed its closest point to our home star, known as perihelion, on Jan. 20, reaching a minimum distance of around 52 million miles (84 million km) from the solar surface, Live Science’s sister site Space.com previously reported.

It will soon make its closest approach to Earth, on Tuesday (Feb. 17), when it will be around 94 million miles (151 million km) from our planet — roughly the same distance away as the sun.

Going, going, gone

According to the researchers, it could take several decades or even centuries for Comet Wierzchoś to officially leave the solar system. But once it has, it will spend millions if not billions of years drifting through the Milky Way, sporadically passing through other alien star systems on its way.

This is exactly what happened to the interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, which made headlines last year as it shot through the inner solar system, having been kicked out by its home star likely long before the sun was born.

3I/ATLAS was first spotted in July and reached perihelion in late October, before swinging past Earth in mid-December. During this period, it displayed many unusual characteristics, which led some scientists to controversially propose that it may be an alien spacecraft — despite overwhelming evidence that it is a natural comet.

It is now on its way back out of the solar system and will likely pass through many other star systems, much like Comet Wierzchoś eventually will.

How to see C/2024 E1 (Wierzchoś)

Since Comet Wierzchoś passed perihelion, it has become significantly brighter and grown a long tail of gas and dust, allowing astrophotographers to snap spectacular shots of it speeding across the night sky. Austrian astrophotographer Gerald Rhemann captured one of the best photos of the iceball on Jan. 26 from a night sky reserve in Namibia (see above).

Many of these photos, including Rhemann’s, show the comet’s coma glowing green. This rare hue is likely tied to its high carbon content, as seen in previous comets, although the exact cause of its coloration has not been reported on by researchers.

The emerald iceball will not become bright enough to be visible to the naked eye. However, it can be easily spotted with a decent telescope or pair of stargazing binoculars.

From the Northern Hemisphere, it will remain observable over the next few weeks and can be best spotted above the southwestern horizon after sunset, as it passes through the constellation Sculptor, according to EarthSky.com. However, it will be easier to spot from the Southern Hemisphere.

For more information on exactly when and how to see the comet for yourself, you can visit TheSkyLive.com.

2026 is shaping up to be another bumper year for comet enthusiasts, following on from the excitement of 3I/ATLAS, as well as other comets like Lemmon and SWAN, last year.

In recent weeks, astronomers have spotted a new “sungrazer” comet, dubbed C/2026 A1 (MAPS), which could potentially become bright enough to be seen with the naked eye during the daytime in early April — if it survives its extremely close slingshot around the sun.

Another hefty iceball, dubbed C/2025 R3 (PanSTARRS), could also become visible without a telescope as it nears its closest points to both the sun and Earth in late April.

With the help of the newly operational Vera C. Rubin Observatory, some researchers are also hoping that we may soon find many more hidden objects — potentially including the solar system’s next interstellar visitor.