Scientists have analyzed the genome of a 14,400-year-old woolly rhino from a piece of its flesh found in the stomach of an ancient wolf pup. The results are giving experts insight into the woolly rhino’s extinction, which probably happened rapidly due to climate change.

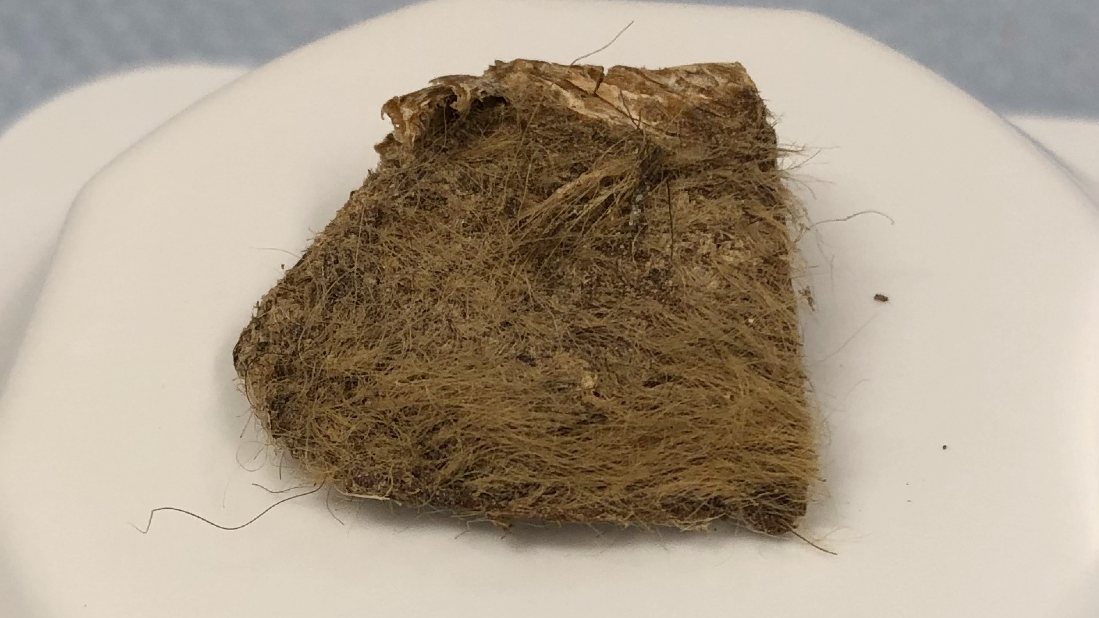

The woolly rhino (Coelodonta antiquitatis) tissue was found inside the mummified remains of a wolf pup, which was initially discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2011. A subsequent necropsy of the pup revealed its final meal: It dined on one of the last woolly rhinos on Earth. But now, scientists have worked out how to sequence the animal’s full genome from the undigested bits of rhino flesh.

“Sequencing the entire genome of an Ice Age animal found in the stomach of another animal has never been done before,” Camilo Chacón-Duque, a bioinformatician at Uppsala University in Sweden and co-author of the new study, said in a statement.

In the new research, published Wednesday (Jan. 14) in the journal Genome Biology and Evolution, researchers analyzed the woolly rhino muscle tissue and compared it with older examples to investigate the species’ population size and level of inbreeding just prior to its extinction. That chunk of meat has provided unprecedented information about the demise of the woolly rhino.

Many species that go extinct leave clues to their decline in their geographic range, their population size, and their genomes. As populations of an animal decrease, they can become concentrated in a particular area. For example, woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) persisted until about 4,000 years ago on a remote island in Siberia. But their small population contributed to inbreeding, and this lack of genetic diversity may have ultimately doomed the mammoth. (Although another study suggests that these island mammoths died in a random mystery event.)

The woolly rhino, however, was widespread across northern Eurasia until about 35,000 years ago. Its geographic range contracted over time, and the species became concentrated in northeastern Siberia, before going extinct around 14,000 years ago. The piece of woolly rhino tissue discovered in the wolf pup’s stomach was carbon-dated to 14,400 years ago, meaning the woolly rhino was likely one of the last of its kind.

Researchers generated the woolly rhino’s genome from the preserved muscle tissue and compared it with two older genomes dated to 18,000 and 49,000 years ago. They discovered that the three rhinos had similar levels of inbreeding and genetic diversity, suggesting that there was a relatively stable woolly rhino population in northern Siberia until at least 14,400 years ago, and that their extinction must have happened rapidly after that.

“Our results show that the woolly rhinos had a viable population for 15,000 years after the first humans arrived in northeastern Siberia, which suggests that climate warming, rather than human hunting, caused the extinction,” study co-author Love Dalén, an evolutionary genomics professor at the Centre for Palaeogenetics in Sweden, said in the statement. The results build on previous work by several of the same researchers.

Rapid changes in the world’s climate happened toward the end of the Pleistocene epoch (the last ice age), and many large mammals went extinct. The disappearance of the woolly rhino lines up with a period called the Bølling-Allerød interstadial, which involved an abrupt warming of the Northern Hemisphere’s climate from around 14,700 to 12,900 years ago. This dramatically warmer climate may have wiped out the favored foods of the cold-adapted, herbivorous woolly rhino and thus contributed to their swift decline.

While the new genome does not resolve all the mysteries surrounding the extinction of the woolly rhino, the researchers demonstrated that it is possible to recover the DNA of one animal from inside another one.

“It was really exciting, but also very challenging, to extract a complete genome from such an unusual sample,” study lead author Sólveig Guðjónsdóttir, a researcher at Stockholm University, said in the statement.

The researchers hope their achievement will pave the way for future DNA and genomic analysis of animal tissues from “unlikely sources.”