An experimental treatment uses specialized neurons derived from stem cells to “soak up” triggers of pain and inflammation in the arthritic knees of mice.

This lab-mouse experiment suggests the therapy could potentially help with chronic pain in people, caused by conditions like osteoarthritis, for example. The hope is that the “pain sponge” could enable patients to stop relying on opioid medications for pain relief, the researchers say.

“The possibility that the therapy could both relieve pain and slow cartilage degeneration is particularly compelling for osteoarthritis,” Chuan-Ju Liu, an orthopedics professor at Yale University who wasn’t involved in the study, told Live Science.

How the pain sponge works

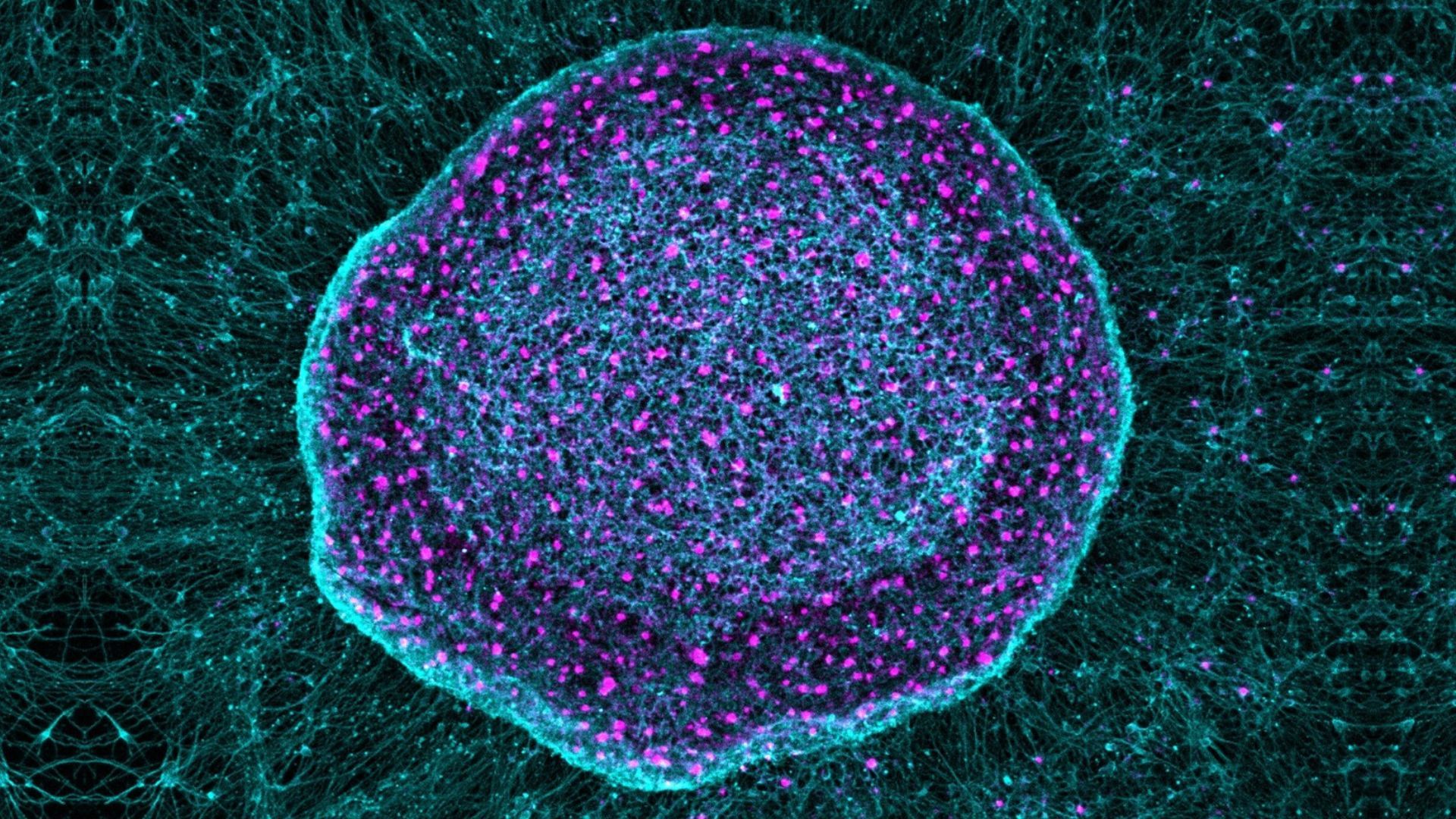

The therapy, known as SN101, uses human pluripotent stem cells (hPSC), which can differentiate into any type of cell in the body. In the study, led by Gabsang Lee, a neurology professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, researchers engineered the hPSC to differentiate into specialized sensory neurons.

These neurons effectively worked as a sponge for inflammatory pain signals. They sequestered the signals before they could be transmitted to the brain and cause pain.

Theoretically, the therapy could work for any kind of chronic pain, said Daniel Saragnese, co-founder of SereNeuro Therapeutics, the biotech company developing SN101. That said, the researchers have so far tested its effectiveness for only osteoarthritis, the most common form of arthritis.

The degenerative condition is characterized by inflammation and chronic pain that affects the joints, mainly the hips, knees, lower back and neck. It causes pain and stiffness, as well as inflammation driven by the breakdown of bone, cartilage and other tissues. There is no cure.

Currently, osteoarthritis symptoms are managed with lifestyle changes, including physical therapy, and various pain relievers, such as over-the-counter and topical painkillers, opioids, and steroid injections.

In the context of neurodegenerative diseases — such as multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease — scientists have been working on using hPSCs to replace or repair damaged neurons. With SN101, though, the researchers are taking an alternative approach. The new hPSC-derived neurons are injected at the site of inflammation and exist alongside other pain-sensing neurons, rather than replacing them.

The new neurons serve as biological decoys, binding nearby inflammatory factors before they can be picked up by the body’s original neurons.

Potential pros of SN101

Chronic pain, which is defined as pain that lasts three months or more, is often managed with opioid drugs that bind to receptors in the body to reduce the intensity of pain. However, opioids cause unwanted side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, and carry a risk of addiction.

Despite their downsides, it is estimated that about 9% of patients with knee osteoarthritis turn to opioids, which can lead to excessive, long-term use. As such, scientists are always on the lookout for safer and more efficient pain-management techniques.

By using biologically complex cells that naturally express multiple pain receptors, SN101 may more closely reflect the way pain and inflammation manifest in living tissues, Liu said. This could help snuff out pain at its source. Opioids, on the other hand, bind to receptors in the brain to temporarily block painful sensations, so they don’t get at the signals at the root of pain.

“However, this work remains at a preclinical stage,” Liu emphasized.

The research will need to pass significant milestones before human use, including formal toxicology studies, long-term safety assessments, and first-in-human clinical trials, he said. Nonetheless, he called the idea behind the therapy “innovative.”

The researchers pointed out several limitations in their recent study that would need investigation before SN101 could be deemed safe for humans. One is the treatment’s immunogenicity — that is, whether it triggers a harmful immune response in the body. Another limitation is that human and mouse knee joints are very different, so some results from the arthritic mouse study might not translate to people.

“Human joints are larger [than mouse joints], more mechanically complex, and subject to decades of cumulative stress,” Liu noted. Additionally, “pain processing and immune-neuronal interactions can differ substantially between mice and humans, which may affect both therapeutic efficacy and durability.”

Ectopic engraftment of nociceptive neurons derived from hPSCs for pain relief and joint homeostasis. Zhuolun Wang, Weixin Zhang, Ju Wang, Zhiping Wu, Xu Cao, Junmin Peng, Gabsang Lee, Xinzhong Dong. bioRxiv 2025.12.16.694733; doi: https://doi.org/10.64898/2025.12.16.694733