Predicting earthquakes before they happen is currently impossible, but scientists are edging closer and closer with new and innovative ways to monitor movements in Earth’s crust. In this excerpt from “When Worlds Quake: The Quest to Understand the Interior of Earth and Beyond” (Princeton University Press, 2026), author Hrvoje Tkalčić, the head of geophysics at the Australian National University, delves into the reasons why earthquake prediction is so tricky, looking at the “Parkfield Experiment,” where scientists waited nearly 20 years for an earthquake on the San Andreas Fault to strike.

An approximate answer to these comments could be given with the following targeted question: “We still can’t beat malignant diseases, but should we stop researching because of that?”

We are used to discussions about earthquake causes after every event, particularly in the places where the world’s earthquakes occur. There are discussions about their frequency, and quite often, there are those who claim they could recognize the coming earthquake in something else. Whether it’s a full moon, a planetary conjunction, too much rainfall, bone pain, overexploitation of the planet’s resources or greed, people tend to believe that earthquakes have simpler explanations than physical forces in the interior of the Earth and, of course, that they can be predicted.

Let’s travel to California in the 1970s and 80s, to a small, picturesque town of only 18 inhabitants — Parkfield — located between San Francisco and Los Angeles, near the central part of the San Andreas Fault. You’re probably wondering why. Well, this small town is known to the seismological world for its turbulent geological history. Namely, on average, significant earthquakes have occurred in Parkfield every 22 years since the middle of the 18th century.

But it was fascinating that the recorded seismograms for the earthquakes of 1922, 1934 and 1966 were almost identical, one wiggly seismogram line to the other. In addition, the 1934 and 1966 earthquakes had foreshocks — about 17 minutes before the main shock — whose seismograms also looked very similar.

You wonder how such a thing is even possible. Such similarity of seismograms is possible only if the same fault surface is always activated and recorded with the same instrument at sufficiently long waves. Of course, the shorter the waves, the greater the differences. In other words, you have a source — an earthquake and a receiver — a seismometer at fixed locations, and waves propagating between them through the same material. So, you have a perfect natural laboratory and an experiment set up in it. You just have to wait long enough.

Scientists, therefore, had good maps in hand to investigate the mechanisms of earthquakes that recur from time to time on an active, well-monitored fault. Since the mid-1980s, they have installed a whole arsenal of instruments near Parkfield and along the fault: powerful seismographs, then strainmeters, which measure rock deformation at a depth of 650 feet (~200 meters) along the fault, magnetometers for measuring the intensity of the magnetic field, creepmeters, which measure displacements on the surface along the fault, and other scientific “weaponry.” They forecasted with 90 to 95% confidence that the next earthquake there would occur between 1985 and 1993. Some of the key questions were:

1. How is stress distributed in space and time on the fault due to the action of tectonic forces before and after the earthquake?

2. Do earthquakes repeat at an average time interval, or is each earthquake unique, a story in itself?

3. How do the structure of faults and surrounding rocks affect the nucleation of smaller earthquakes and the possibility of larger ones and their distribution in time and space?

They wondered what the deformation we measure on the surface could tell us about the stress distribution on the fault, and they hoped for a positive result — confirmation of the predictions for earthquake occurrences between 1985 and 1993. They waited and waited. In those years, I worked once a week with colleagues at the U.S. Geological Survey California office in Menlo Park, in the northwestern part of Silicon Valley, where I was able to observe some scientists involved in the experiment.

Eventually, a magnitude 6.0 earthquake did happen in Parkfield, but not until 2004. We greeted the most watched and studied earthquake in human history with a huge question mark above our heads; it occurred 11 years after its forecasted time. Devastating. That’s why the “Parkfield Experiment” left a bitter taste of disappointment in the mouth. But, as they say, only those who dare to fail eventually succeed. Research continued.

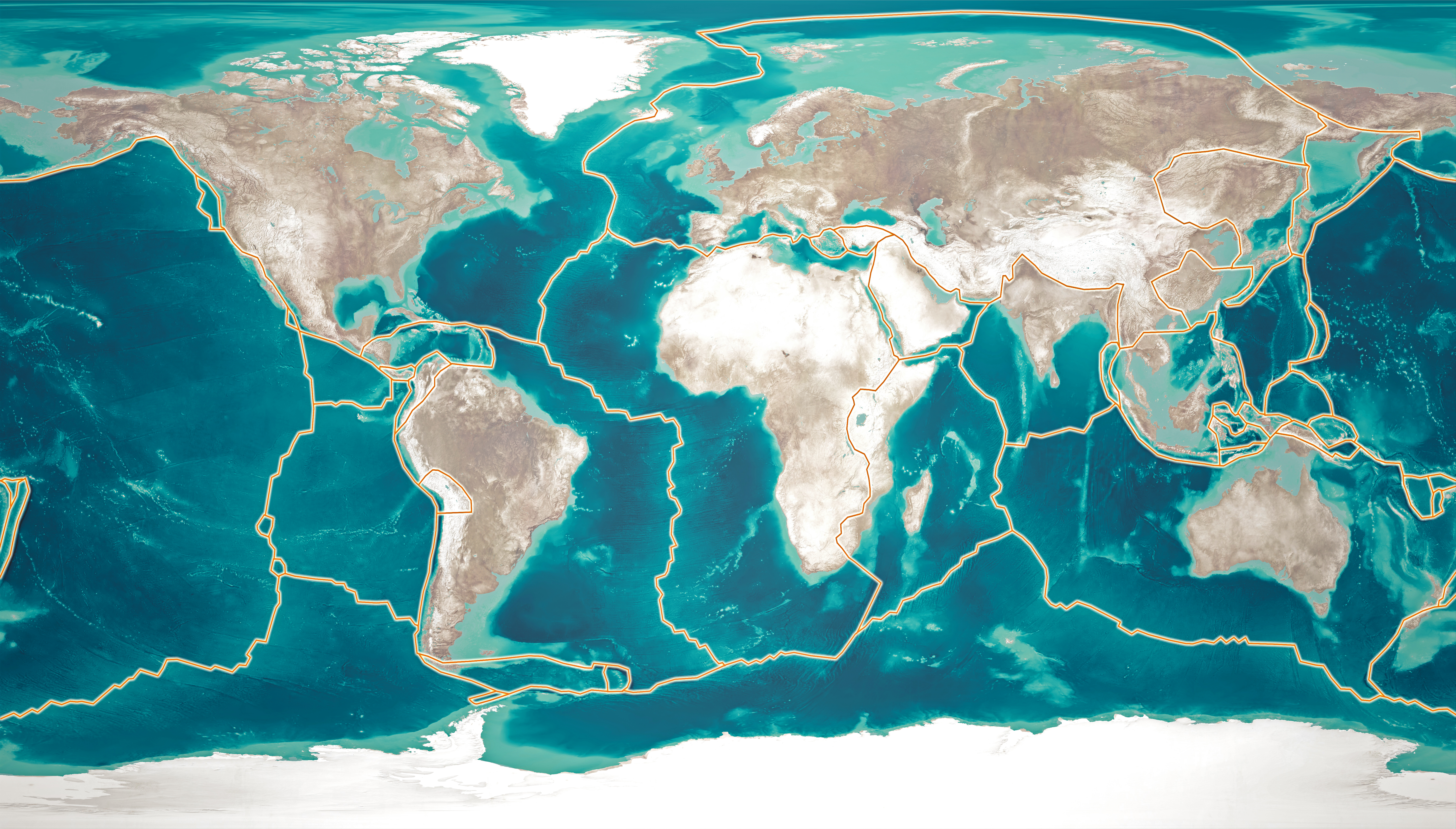

Why is earthquake prediction so tricky? Each fault is different — some of them we know about, but many we don’t — earthquake catalogs don’t go back far enough, and, after all, underground architecture is entirely invisible to us.

We do not know how deep the fault reaches, whether it is a flat or curved surface, whether its surface is smooth or rough, whether and where it touches other faults, the chemical composition of the rocks on one and the other side of the fault, or their physical properties, for example, strength and porosity. We do not know precisely how the deformation we observe on the surface of the Earth can be related to the deformation and stress in the depth of the fault. We also do not know many other factors. A forecast can be made, but by its very nature, it must be probabilistic and taken with a grain of salt. So, how do we proceed?

Not everything is so negative. The first good news is that seismic hazard maps exist in most countries. They are well made, but of course, they must be constantly updated. The other good news is that, based on fundamental knowledge of physics and the propagation of seismic waves through the interior and across the surface of the Earth, we can predict how the ground and some buildings will behave during an earthquake, and that is already a major benefit.

This is possible because of basic science and seismological research on the nature of the subsurface, in a similar way that radiologists can illuminate the inside of the human body. Ironically, earthquakes help us because they serve as a source of waves illuminating the Earth’s interior. It is possible to predict infrastructure behavior during earthquakes due to the development of engineering, construction, computer science and numerical methods. Either way, those hazard maps serve as input for engineers, builders and insurance companies.

In the end, the most positive thing is that modern studies involving laboratory models and artificial intelligence are being carried out across the world, aimed in the direction that one day we will be able to predict earthquakes. Certainly not without major investment in science and technology, which will need to continue to develop. This might even take us to the point where we will have to place thousands or millions of microsensors on every fault in the Earth’s interior and then monitor the strain in real time.

In a way, we will have a “crystal ball” — an insight into the dynamics and future behavior of faults. In fact, we are already doing it today, but we have only scratched the surface of the Earth with the help of satellites. InSAR, LIDAR and GPS are just some of the networks and methods that give us an insight into where the Earth’s crust is most stressed from surface deformations.

The stress or tension build-up mechanism on a fault is still under investigation. It is most likely that the hot rocks of the Earth’s continental crust beneath approximately 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) of depth are ductile, and this rock mass “flows” at a higher speed than on the surface, but without earthquakes, and the upper part of the crust therefore bends and the stress along the fault surface increases. However, how this stress is distributed in space is not yet known.

Furthermore, laboratory experiments at high pressures and temperatures give us insight into how hard rocks are and how strain and stress are related. The chemical and physical structure of the soil is examined by drilling around the fault. Old tree trunks are explored, and excavations are made to detect historical earthquakes on rock samples.

Investments are made in studying the deeper interior of the Earth and the mechanism of earthquakes using seismic waves and tomography methods. Investments are also made in mathematical geophysics, as well as in machine learning and improved techniques for processing enormous amounts of digital data. Investments are also made in alarm systems based on the detection of P waves. Even a few seconds of warning before the arrival of S waves can be crucial to saving people and infrastructure. Likewise, investments are being made in modern construction resistant to earthquakes.

But the conclusion is that, unless you want to move to stable parts of the continents, somewhere in Siberia, to the northernmost, permanently frozen parts of Canada, or the remote regions of the Australian Outback seldom struck by earthquakes, we need to learn to live with earthquakes.

Adapted from When Worlds Quake: The Quest to Understand the Interior of Earth and Beyond. Copyright © 2026 by Hrvoje Tkalčić. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.