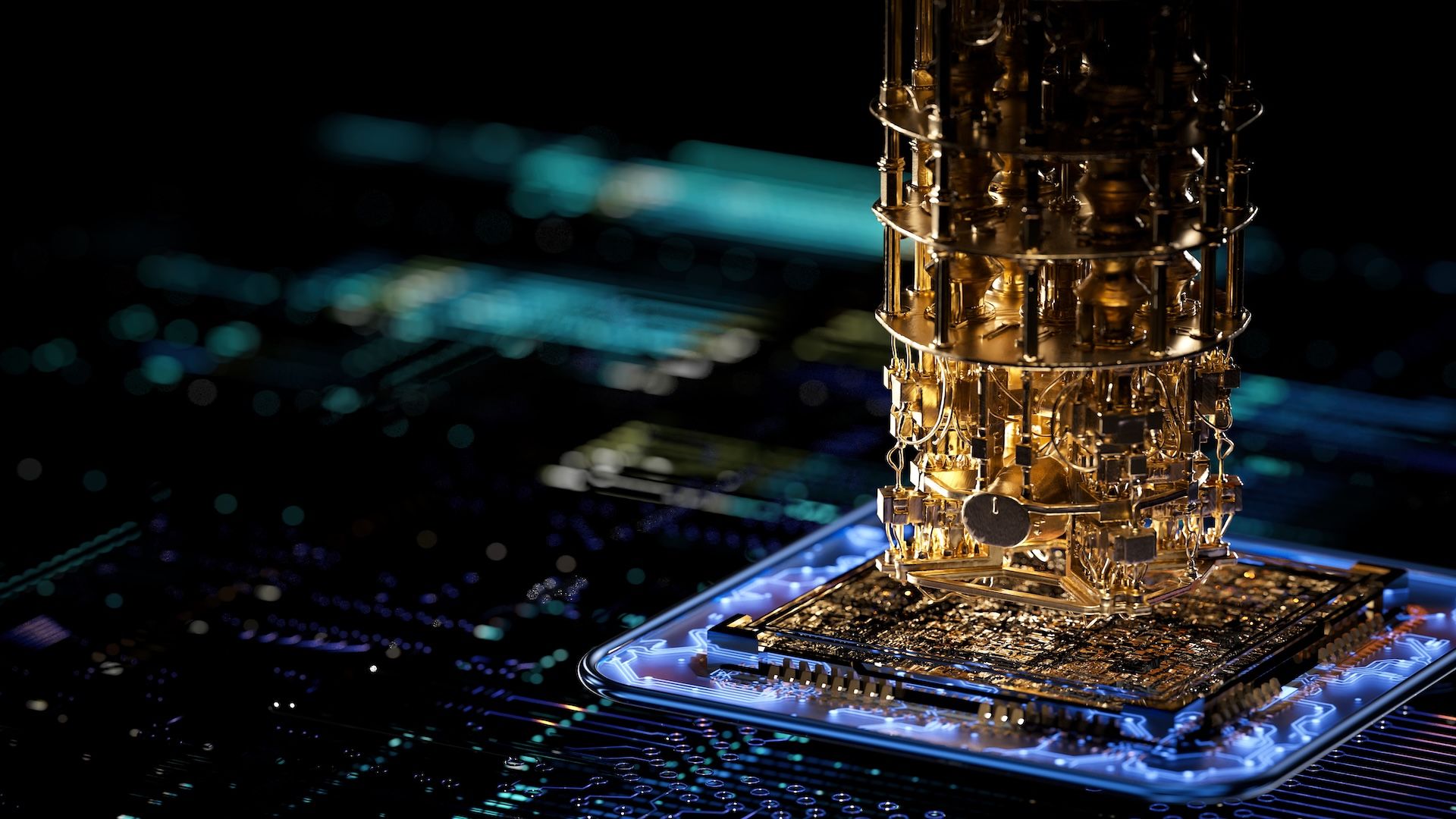

Scientists have developed a new fabrication method for creating superconducting quantum bits (qubits) that could remain coherent for three times longer than current state-of-the-art systems in labs — allowing them to conduct more powerful quantum computing operations.

The new technique, described in a study published Nov. 5 in the journal Nature, relies on the use of a rare earth element called tantalum. This belongs to the “transition metals” group of the periodic table and is “grown” on minerals such as tantalite and silicon by building up a metallic film atom-by-atom.

“The real challenge, the thing that stops us from having useful quantum computers today, is that you build a qubit and the information just doesn’t last very long,” said Andrew Houck, Princeton’s dean of engineering and co-principal investigator of the study, in the study. “This is the next big jump forward.”

Decoherence and imperfection

Coherence in quantum computing is a measure of how long a qubit can maintain its wave state. When qubits decohere, they lose information. This makes maintaining coherence one of the biggest challenges in quantum computing.

Scientists have spent some years trying to harness tantalum as a material to develop qubits. When a superconducting material such as tantalum is cooled to near absolute zero, circuits built within the material can operate with close to no resistance. This allows for faster quantum operations, but the speed and number of operations are fundamentally limited by how long qubits can maintain their information states.

An advantage of tantalum is that it’s easier to scrub free of contaminants that can lead to imperfections in the manufacturing process, where any irregularity can cause affected qubits to decohere faster. Tantalum’s inert resilience protects it from certain state changes related to corrosion and molecular displacement; it won’t even absorb acid when immersed. This makes it a perfect candidate for use as a superconducting material for quantum computing, the scientists said in the study.

But keeping the qubit material free from defects is only half the battle. The manufacture of a quantum processor requires both a base layer material and a substrate. In previous experiments, scientists achieved state-of-the-art quantum computing results using processors built with a tantalum base layer and a sapphire substrate. These experiments were successful, but coherence rates were still under one millisecond.

The Princeton team replaced the sapphire substrate used in those experiments with a high-resistivity silicon developed using proprietary techniques. According to the study, they achieved coherency rates as high as 1.68 milliseconds on systems as large as 48 qubits — marking an all-time best for superconducting qubits.

The new qubit design is similar to those used in superconducting quantum processors developed by leading companies such as Google and IBM. Houck even added that “swapping Princeton’s components into Google’s best quantum processor, called Willow, would enable it to work 1,000 times better.”

What this means for the quantum computing industry remains unclear. While the scientists have progressed the coherence rates of qubits significantly, challenges remain. Chief among them is the availability of tantalum. As of 2025, tantalum is considered a scarce metal with most mining taking place in Africa.

While the new qubits significantly increase coherence, they still need to be tested at larger sizes using wafer-scale chipsets before they can be integrated with today’s commercially deployed quantum computers.