Folk medicine practitioners in 16th-century Europe left ingredients and fingerprints smudged on their manuals while developing remedies for minor ailments. Now, researchers are studying the chemical traces Renaissance people left behind to understand how they experimented with novel cures.

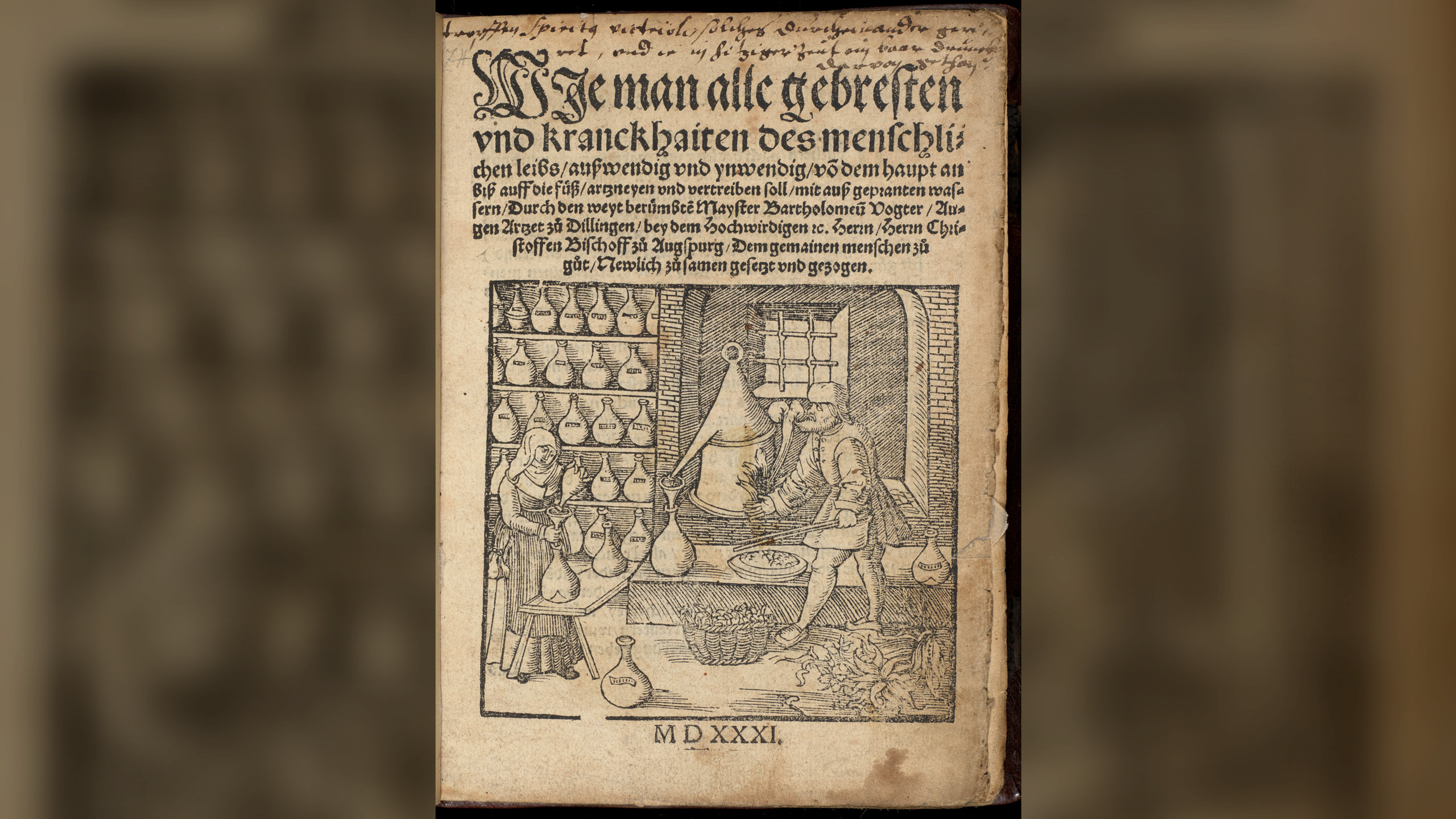

Two German medical manuals — “How to Cure and Expel All Afflictions and Illnesses of the Human Body” and “A Useful and Essential Little Book of Medicine for the Common Man” — were published in 1531 by eye doctor Bartholomäus Vogtherr. His systematically gathered recipe books for common ailments, like hair loss and bad breath, quickly became bestsellers in Renaissance domestic medicine.

In a study published Nov. 19 in the journal American Historical Review, researchers reported their success at using proteomics analysis to identify the materials that medical practitioners were using as they flipped through Vogtherr’s book centuries ago.

“People always leave molecular traces on the pages of books and other documents when they come into contact with paper,” study co-author Gleb Zilberstein, a biotechnology expert and inventor, told Live Science in an email. “These traces include components of sweat, sometimes saliva, metabolites, contaminants, and environmental components.” Proteins and peptides are part of this mixture and are “often invisible to the naked eye,” Zilberstein added.

To analyze the proteins and peptides (molecules made up of strings of amino acids), the researchers first used specially made plastic diskettes to capture the proteins from the paper. Then, they used mass spectrometry to detect individual amino-acid chains that could be identified as specific proteins.

In total, the researchers sequenced 111 proteins from the Vogtherr manual. Most of the proteins were from the practitioners themselves, the team wrote in the study, but several were associated with plants or animals that were featured in the curative recipes.

“Peptide traces of European beech, watercress, and rosemary were recovered next to recipes recommending the use of these plants to cure hair loss and to strengthen the growth of facial and head hair,” the researchers wrote, and “lipocalin recovered next to a recipe that recommends the everyday use of human feces to wash one’s bald head for overcoming hair loss points to reader-practitioners following such instructions.”

Other collagen peptides were harder to identify. One extracted protein could match either tortoise shell or lizards. While 16th-century medical literature mentions that turtle shells were reported to cure edema (fluid retention), pulverized lizard heads were used to prevent hair loss. But the protein was discovered on a page next to Vogtherr’s hair-growth recipes, suggesting that the user of the medical manual may have experimented with lizards as hair-care therapy.

Another surprising discovery was the recovery of collagen peptides that may match a hippopotamus next to recipes discussing ailments of the mouth and scalp. Hippos were a popular curiosity across early modern Europe, and their teeth were thought to cure baldness, severe dental problems and kidney stones. The traces of hippo proteins may suggest that Vogtherr’s readers struggled with tooth issues, the researchers wrote, as recipes to cure stinking breath, mouth ulcers and black teeth are dog-eared and annotated in the manual.

“Proteomics help contextualize both the symptoms that people possibly struggled with when turning to recipe knowledge for help and the bodily effects of recipe trials and treatments,” the researchers wrote.

The scientists hope their novel analysis of invisible proteins clinging to centuries-old books will contribute to a better understanding of early modern household science.

“In the future, we plan to expand this work and examine other historical books,” Zilberstein said, as well as “to identify individual readers based on their proteomic data.”