QUICK FACTS

Milestone: Discovery of radium and polonium

Date: Dec. 26, 1898

Where: Paris

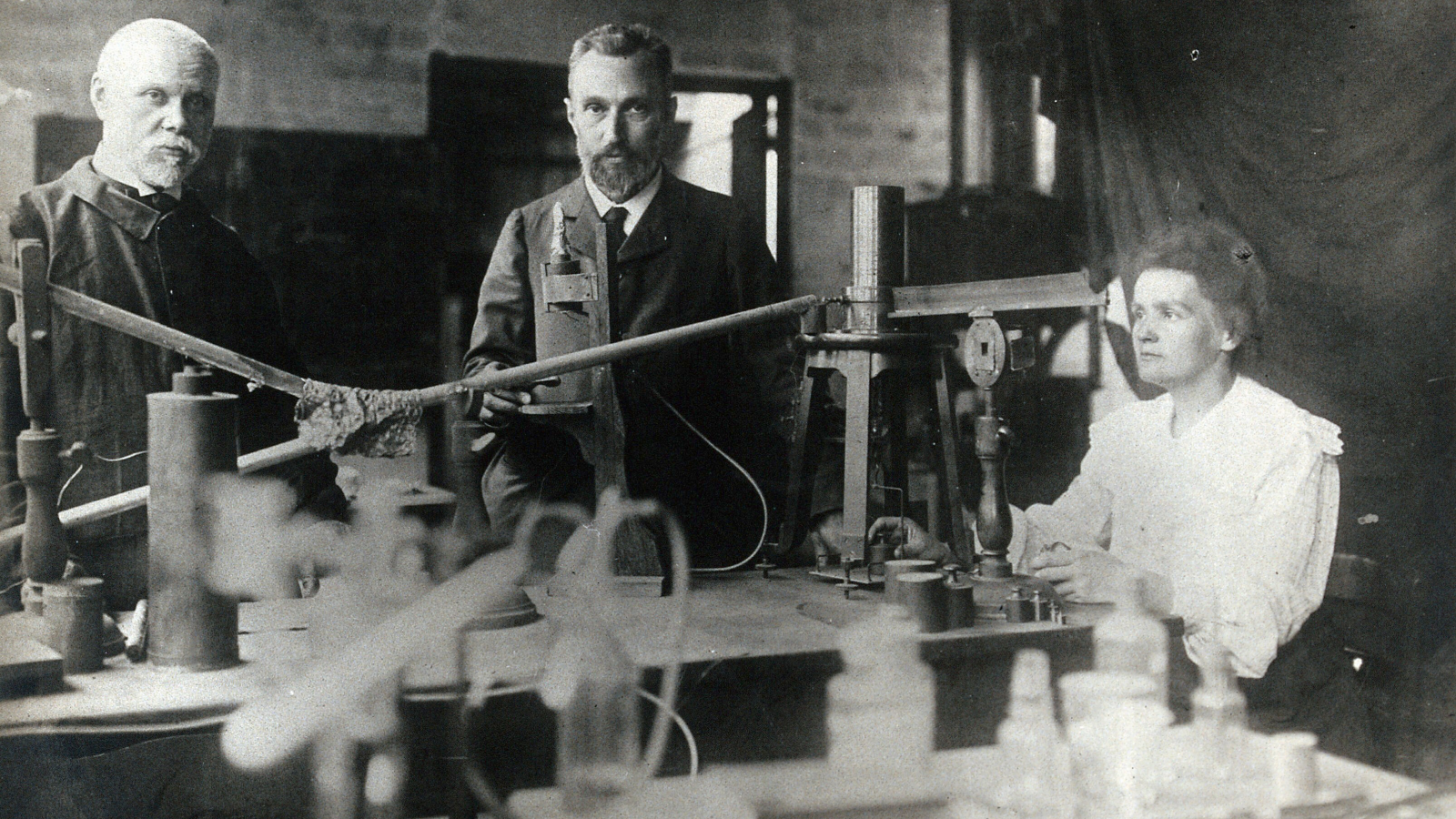

Who: Marie and Pierre Curie, Gustave Bémont

On this day, chemists discovered a substance 900 times more radioactive than uranium. Their research led to unprecedented medical breakthroughs and worldwide fame — but it would also kill one of them.

Marie Curie was a medical student at the Sorbonne, a university in Paris, when she decided to study the new field of radiation for her thesis. In 1895, Wilhelm Röntgen discovered powerful “Röntgen rays,” which would eventually be dubbed X-rays. The following year, Henri Becquerel accidentally discovered much weaker rays emitted by uranium salts would fog up photographic plates just like light rays did — even in the absence of light.

Curie realized that she wouldn’t have to read a long list of prior papers on the newfangled subject before diving into experimental work, according to the American Institute of Physics. Curie’s husband, Pierre, found her a workspace in a musty, crowded storeroom at his institution, the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry. He soon became so fascinated with her research that he abandoned his own to pursue hers.

Key to Marie Curie’s research was the piezoelectric quartz electrometer. The device, invented by her brother-in-law, Jacques Curie, measured the weak electrical currents produced by radioactivity.

“Instead of making these bodies act upon photographic plates, I preferred to determine the intensity of their radiation by measuring the conductivity of the air exposed to the action of the rays,” Curie wrote in a 1904 article for Century magazine.

The damp storeroom messed with her results, but she ultimately discovered that the intensity of this radiation depended on the concentration of uranium in the minerals she studied. She speculated that something intrinsic to the atomic structure of uranium must be at play.

Working with her husband Pierre and Gustave Bémont, the head of chemistry at the Higher School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry of the City of Paris, they began to study pitchblende, a black mineral rich in uranium often found in deposits alongside silver.

Curie noticed that it could be much more radioactive than uranium ore itself.

“How could an ore, containing many substances which I had proved inactive, be more active than the active substances of which it was formed? The answer came to me immediately: The ore must contain a substance more radioactive than uranium and thorium, and this substance must necessarily be a chemical element as yet unknown,” Marie Curie wrote in Century magazine in 1903.

Marie Curie deduced that whatever this mysterious substance was, it had to exist only in small quantities yet have a remarkable level of what she had dubbed “radio-activity.” The trio decided to try to separate pitchblende, which can be composed of up to 30 minerals, into its constituent parts to identify the radioactive substance. They used the light spectra of different substances to try to isolate and identify the ingredients.

In July, they pinpointed one mineral that was around 60 times more “radio-active” than uranium, which they named polonium. And on Dec. 21, they found another — called radium — that was an unprecedented 900 times more radioactive than uranium. They described both new substances during a talk at the French Academy of Sciences on Dec. 26.

The Curies would go on to isolate the radioactive elements over the next several years, while working in a poorly ventilated shed in the courtyard across from the original storeroom.

Their research on radiation earned the Curies and Becquerel the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1903. (Marie was originally going to be passed over, but she received the prize only after her husband, Pierre, insisted the committee credit her work.) Marie would earn another Nobel Prize in 1911, this time in chemistry, for her work on radium.

Pierre was killed by a horse-drawn carriage in 1906, but Marie would go on to advocate for the use of X-rays in medicine — including developing vehicles that could provide mobile X-rays for soldiers on the battlefield during World War I. She also noted that radium killed off diseased cells faster than healthy ones, a principle that would later inspire the development of radiotherapy for cancer treatment.

Radium caused frequent radiation sickness and burns in both Curies. Marie’s radiation exposure likely killed her; she died in 1934 at age 66 due to aplastic anemia, a type of leukemia that can be caused by radiation damage to bone marrow. The notebook she used to document her 1898 discovery is still radioactive and is stored in a lead box.