Harpoons crafted from the bones of humpback and southern right whales show Indigenous groups in what is now Brazil were hunting whales 5,000 years ago.

The discovery, which included 118 whale bones and crafted artifacts, reveal that prehistoric whaling was not confined to people in temperate and polar climates in the Northern Hemisphere, according to a study published Jan. 9 in the journal Nature Communications.

“Whaling has always been enigmatic,” because it’s difficult to distinguish bone tools made from actively hunted and stranded animals in the archaeological record, study co-author André Carlo Colonese, a research director at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, told Live Science.

So the new tools are significant because their discovery alongside multiple bone remains from members of the same species represents some of the oldest evidence of active whale hunting in the world, the authors wrote in the study.

Prehistoric whaling

For prehistoric people, whales provided huge feasts, oil for warmth, and bones for tools and cultural ornaments and accessories. Although coastal communities have opportunistically salvaged these resources from beached whales for at least 20,000 years, the evidence of active hunting is much younger. For example, people hunted large whales with deer bone harpoons 6,000 years ago in what is now South Korea, and harpoons from around 3,500 to 2,500 years ago have been uncovered in the Arctic and sub-Arctic.

Colonese and his team did not originally set out to investigate early whaling. Instead, they were trying to document the marine species that were used by Indigenous Sambaqui populations in southern Brazil. To do so, they analyzed the molecular signature of precolonial cetacean (whale, dolphin and porpoise) bones at the Joinville Sambaqui Archaeological Museum in Brazil. Of the 118 bone remains with an identifiable cetacean species, most were from southern right whales, but many bones were from humpback whales. Only 37 had been crafted into items such as pendants.

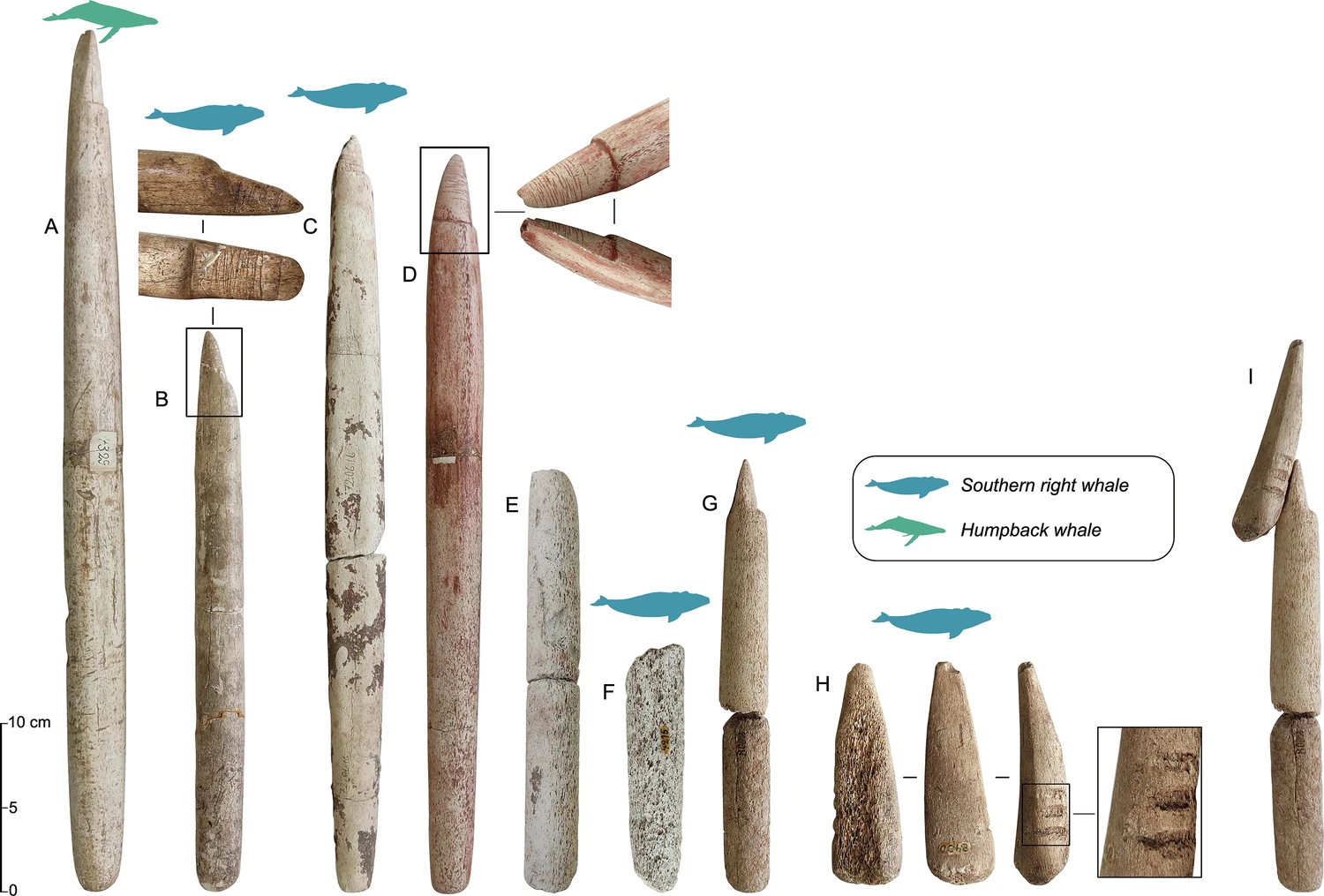

It was “completely random” that one of the museum’s curators brought out a box of what were believed to be sticks, Colonese said. But based on their design, such as hollow centers for a wooden shaft and carved tips, he immediately recognized them as harpoons. The team identified 15 harpoon elements, including heads and shaft components, made from either southern right whale or humpback whale rib bones.

The researchers took tiny samples from two harpoon foreshafts to determine their age, which revealed that the tools were between 4,710 and 4,970 years old. Colonese said he jumped for joy when he saw the results because these are some of the oldest harpoons found anywhere in the world — over 1,000 years older than the Arctic and sub-Arctic examples.

The discovery also showed that these Indigenous populations in Brazil were not simply gathering mollusks and catching fish. “The conventional idea was that the Sambaquis didn’t have the technology” for whaling, Colonese said. “This is telling us that they were actually hunting.”

“It’s a very spectacular, informative discovery,” Jean-Marc Pétillon, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse in France who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Although it’s not clear that these particular harpoons were used to hunt whales — as opposed to other marine animals, such as seals — this new evidence helps to contradict the assumption that whaling was practiced only in the Northern Hemisphere, according to Pétillon.

“Having these people living in southern Brazil in tropical conditions that also did whaling is also a way to change our perspective on these maritime exploitation systems,” he said.

McGrath, K., Montes, T.A.K.d.S., Fossile, T. et al. Molecular and zooarchaeological identification of 5000 year old whale-bone harpoons in coastal Brazil. Nat Commun 17, 48 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67530-w