Astronomers have gotten a rare glimpse at four baby planets as they’re growing up, and it reveals something surprising: These toddler worlds are getting lighter as they age.

The quadruplet worlds orbit in tightly packed paths around the star V1298 Tau, a young system that’s just 20 million years old (compared with our sun’s 4.5 billion years) located about 350 light-years from Earth. A new analysis, which drew on a decade of observations, shows that the planets are surprisingly lightweight, with low densities — so puffed up, in fact, that researchers likened them to Styrofoam.

Those older systems are often crowded with planets between the sizes of Earth and Neptune on tight, Mercury-like orbits. The origins of such worlds have remained one of astronomy’s enduring mysteries.

“What’s so exciting is that we’re seeing a preview of what will become a very normal planetary system,” study lead author John Livingston, an assistant professor at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, said in a statement. “We’ve never had such a clear picture of them in their formative years.”

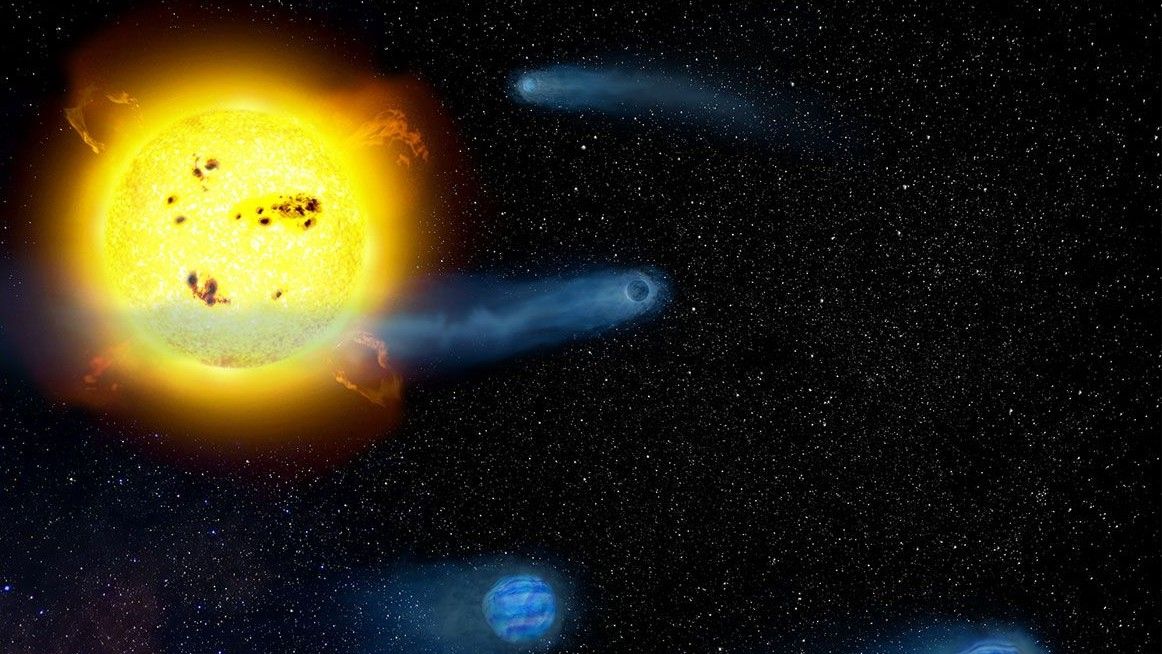

Over time, the bloated worlds around V1298 Tau are expected to shrink as they shed their thick atmospheres, eventually becoming super-Earths and sub-Neptunes — planetary types that are absent from our own solar system but ubiquitous throughout the galaxy.

By capturing the planets at such a pivotal stage of development, the study, published Jan. 7 in the journal Nature, enables astronomers to trace the chaotic processes that sculpt planetary systems over billions of years.

‘I couldn’t believe it!’

The four planets orbiting V1298 Tau were first identified in 2019 in data from NASA’s Kepler space telescope. One is roughly Jupiter-size, while the other three fall between the sizes of Neptune and Saturn.

What immediately set the system apart was its crowded layout of multiple oversized planets packed into relatively tight orbits — a configuration known in only one other system, Kepler-51, among more than 500 known multi-planet systems.

While the planets’ existence was clear, their fundamental properties remained elusive. To pin them down, Livingston and his team embarked on a nearly decade-long observation campaign using half a dozen telescopes in space and on the ground. They tracked the planets as they passed in front of their star — events known as transits, which cause tiny dips in starlight that reveal a planet’s size and orbital period.

Crucially, small variations in the timing of the transits, caused by the planets tugging gravitationally on one another, enabled the team to measure their masses. The technique is especially powerful because it is largely immune to interference from stellar flares common around young stars, the study noted.

But the method only works if astronomers know each planet’s orbital period precisely — and for the outermost planet, V1298 Tau e, that information was missing. Only two of its transits had ever been observed, separated by 6.5 years across observations from Kepler and NASA’s exoplanet-hunting Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) telescope, leaving astronomers unsure how many transits had gone unseen in between, according to the study.

A stroke of good luck came when the ground-based Las Cumbres Observatory network — which operates telescopes in the United States, Chile and South Africa — spotted a third transit, enabling the researchers to finally lock down the planet’s orbit and model the system’s full gravitational choreography.

“I couldn’t believe it!” study co-author Erik Petigura, an assistant professor of astronomy and astrophysics at UCLA, said in the statement. “The timing was so uncertain that I thought we would have to try half a dozen times at least. It was like getting a hole-in-one in golf.”

The results showed that despite being five to 10 times Earth’s radius, the planets have masses only five to 15 times greater than Earth’s, making them among the least dense planets ever discovered, Livingston said.

“By weighing these planets for the first time, we have provided the first observational proof,” study co-author Trevor David, an astrophysicist formerly at the Flatiron Institute in New York, who led the system’s discovery in 2019, said in the statement. “They are indeed exceptionally ‘puffy,’ which gives us a crucial, long-awaited benchmark for theories of planet evolution.”

The team then simulated the planets’ evolution and found that they have already lost much of their original atmospheres and cooled faster than predicted by standard models.

“But they’re still evolving,” study co-author James Owen, an associate professor of astrophysics at Imperial College London, said in the statement. The planets are expected to continue shedding gas and contracting into super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, he said.

“Over the next few billion years, they will continue to lose their atmosphere and shrink significantly, transforming into the compact systems of super-Earths and sub-Neptunes we see throughout the galaxy,” Owen added.