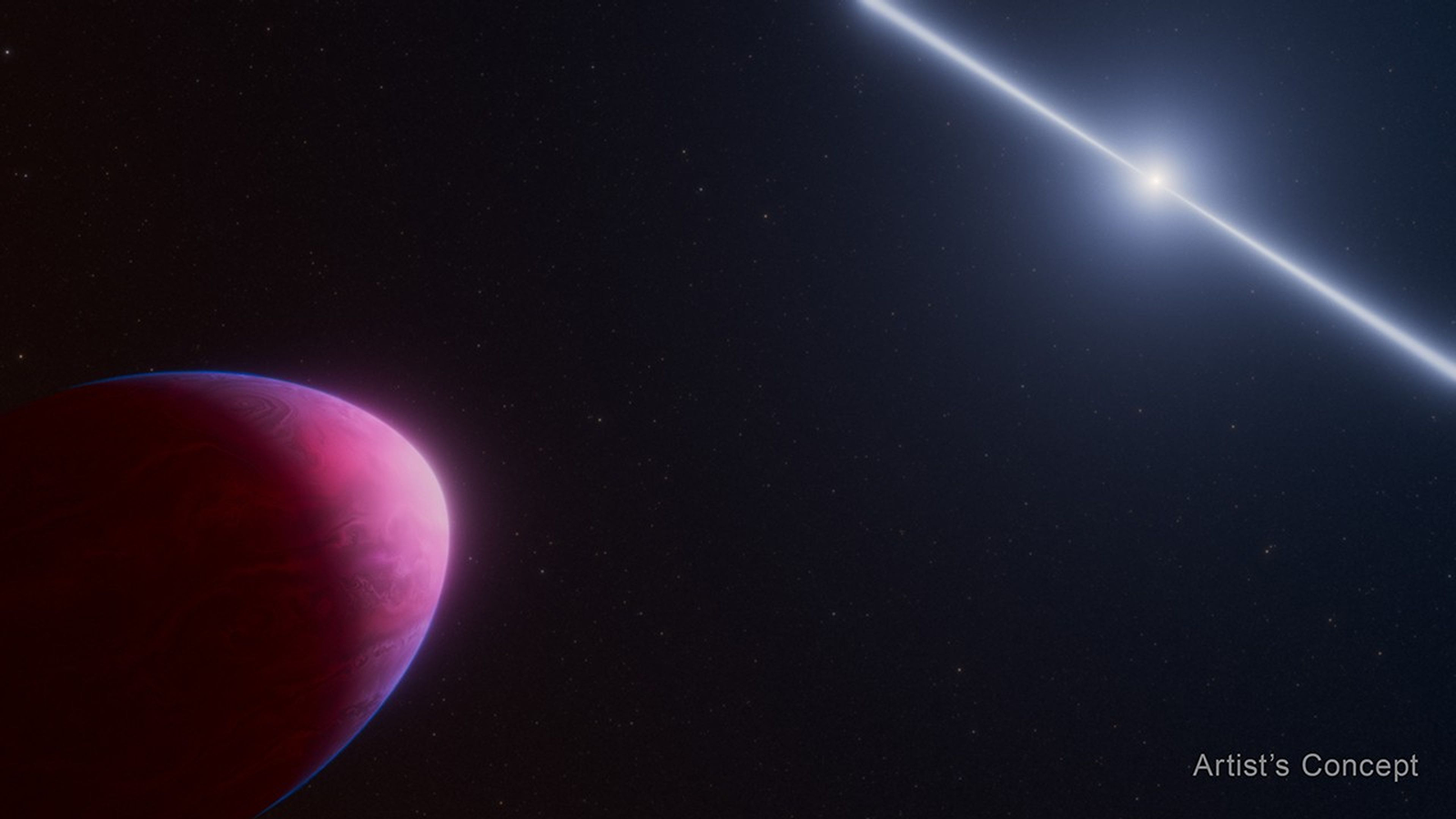

A distant exoplanet appears to sport a sooty atmosphere that is confusing the scientists who recently spotted it.

The Jupiter-size world, detected by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), doesn’t have the familiar helium-hydrogen combination we are used to in atmospheres from our solar system, nor other common molecules, like water, methane or carbon dioxide.

“This was an absolute surprise,” study co-author Peter Gao, a staff scientist at the Carnegie Earth and Planets Laboratory, said in a statement. “I remember after we got the data down, our collective reaction was, ‘What the heck is this?’ It’s extremely different from what we expected.”

Neutron sun

Researchers probed the bizarre environment of the planet, known as PSR J2322-2650b, in a paper published Tuesday (Dec. 16) in The Astrophysical Journal Letters. Although the planet was detected by a radio telescope survey in 2017, it took the sharper vision of JWST (which launched in 2021) to examine PSR J2322-2650b’s environment from 750 light-years away.

PSR J2322-2650b orbits a pulsar. Pulsars are fast-spinning neutron stars — the ultradense cores of stars that have exploded as supernovas — that emit radiation in brief, regular pulses that are visible only when their lighthouse-like beams of electromagnetic radiation aim squarely at Earth. (That’s bizarre on its own, as no other pulsar is known to have a gas-giant planet, and few pulsars have planets at all, the science team stated.)

The infrared instruments on JWST can’t actually see this particular pulsar because it is sending out high-energy gamma-rays. However, JWST’s “blindness” to the pulsar is actually a boon to scientists because they can easily probe the companion planet, PSR J2322-2650b, to see what the planet’s environment is like.

“This system is unique because we are able to view the planet illuminated by its host star, but not see the host star at all,” co-author Maya Beleznay, a doctoral candidate in physics at Stanford University, said in the statement. “We can study this system in more detail than normal exoplanets.”

Formation mystery

PSR J2322-2650b’s origin story is an enigma. It is only a million miles (1.6 million kilometers) from its star — nearly 100 times closer than Earth is to the sun. That’s even stranger when you consider that the gas giant planets of our solar system are much farther out — Jupiter is 484 million miles (778 million km) from the sun, for example.

The planet whips around its star in only 7.8 hours, and it’s shaped like a lemon because the gravitational forces of the pulsar are pulling extremely strongly on the planet. At first glance, it appears PSR J2322-2650b could have a similar formation scenario as “black widow” systems, where a sunlike star is next to a small pulsar.

In black-widow systems, the pulsar “consumes” or erodes the nearby star, much like the myth of the black widow spider’s feasting behavior after which the phenomena is named. That happens because the star is so close to the pulsar that its material falls onto the pulsar. The extra stellar material causes the pulsar to gradually spin faster and to generate a strong “wind” of radiation that erodes the nearby star.

But lead author Michael Zhang, a postdoctoral fellow in exoplanet atmospheres at the University of Chicago, said this pathway made it difficult to understand how PSR J2322-2650b came to be. In fact, the planet’s formation appears to be unexplainable at this point.

“Did this thing form like a normal planet? No, because the composition is entirely different,” Zhang said in the statement. “It’s very hard to imagine how you get this extremely carbon-enriched composition. It seems to rule out every known formation mechanism.”

Diamonds in the air

Scientists still can’t explain how the soot or diamonds are present in the exoplanet’s atmosphere. Usually, molecular carbon doesn’t appear in planets that are very close to their stars, due to the extreme heat.

One possibility for what happened comes from study co-author Roger Romani, a professor of physics at Stanford University and the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology. After the planet cooled down from its formation, he suggested, carbon and oxygen in its interior crystallized.

But even that doesn’t account for all of the odd properties. “Pure carbon crystals float to the top and get mixed into the helium … but then something has to happen to keep the oxygen and nitrogen away,” Romani explained in the same statement. “And that’s where the mystery [comes] in.”

Scientists hope to continue studying PSR J2322-2650b. “It’s nice to not know everything,” Romani said. “I’m looking forward to learning more about the weirdness of this atmosphere. It’s great to have a puzzle to go after.”