Scientists have reconstructed the head of an ancient human relative from 1.5 million year-old fossilized bones and teeth. But the face staring back is complicating scientists’ understanding of early human evolution and dispersal, according to a new study.

The rebuilt fossil skull, called DAN5, shares traits with Homo erectus, the first early human relatives to have modern body proportions and to disperse from Africa. But the skull also has some features associated with the earlier species Homo habilis. The findings suggest a complex evolutionary path from early human ancestors to H. erectus, researchers reported Dec. 16 in the journal Nature Communications.

“We already knew that the DAN5 fossil had a small brain, but this new reconstruction shows that the face is also more primitive than classic African Homo erectus of the same antiquity,” study co-author Karen Baab, a paleontologist at Midwestern University in Arizona, said in a statement. This could mean that the population from the Gona region might have “retained the anatomy of the population that originally migrated out of Africa approximately 300,000 years earlier,” she said.

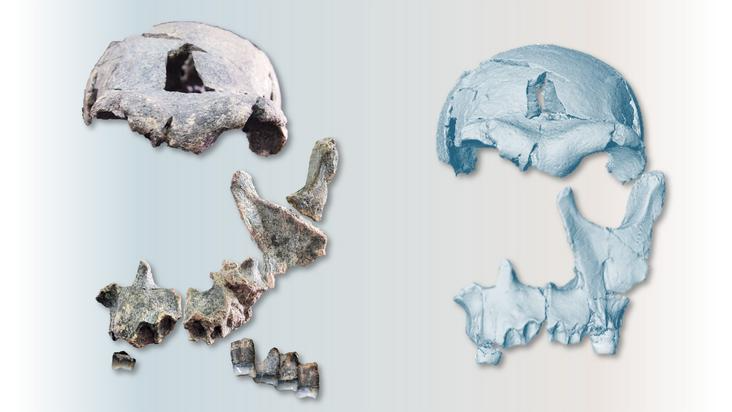

To reconstruct DAN5’s face, the researchers used micro-computerized tomographic (CT) scans of 10 fossils — five fragments of facial bones and five teeth — to build a 3D model. The process was like “a very complicated 3D puzzle, and one where you do not know the exact outcome in advance,” Baab said. “Fortunately, we do know how faces fit together in general, so we were not starting from scratch.”

The shape of DAN5’s braincase was similar to that of H. erectus. But some of the facial features such as large molars and a flat and narrow nose were more similar to features in the older human ancestor H. habilis.

A similar mix of old and new traits was previously observed in 1.8 million-year-old H. erectus fossils from Dmanisi in the Republic of Georgia, which led some scientists to believe that the species evolved in Eurasia from an earlier Homo population. Older H. erectus fossils dating back 1.8 million years have also been found in Africa. But DAN5 is the first African fossil to have the same mixture of attributes as the Dmanisi hominins, which could support the hypothesis that H. erectus evolved primarily in Africa like other hominins before it. Further complicating the picture, though, is the fact that the DAN5 fossils are younger than those from Dmanisi, suggesting the mixture of old and new traits persisted in Africa for at least 300,000 years.

In future work, the team plans to compare the DAN5 fossils to 1 million-year-old human fossils from Europe, including some that have been identified as H. erectus and as Homo antecessor — a later human relative that lived 1.2 million to 0.8 million years ago — to better understand variability in face shape in the early Homo genus. The team also plans to investigate whether DAN5 might be a product of interbreeding between multiple Homo species.

“We’re going to need several more fossils dated between one to two million years ago to sort this out,” study co-author Michael Rogers, an anthropologist at Southern Connecticut State University, said in the statement.