By breaking up clusters of cancer cells, an old heart drug called digoxin may help stop tumors from spreading to other organs, a small trial shows.

The research is in its early days, though, so it will be some time before we know whether it’s useful for treating cancers, including breast cancer, scientists say.

Breast cancer is among the leading causes of cancer deaths in U.S. women, largely due to its ability to spread, or metastasize, from the breast to other parts of the body. These migrating cancer cells can invade vital organs, like the brain or lungs, making treatment more challenging. Standard cancer treatments focus on killing tumor cells but aren’t specifically designed to stop metastasis.

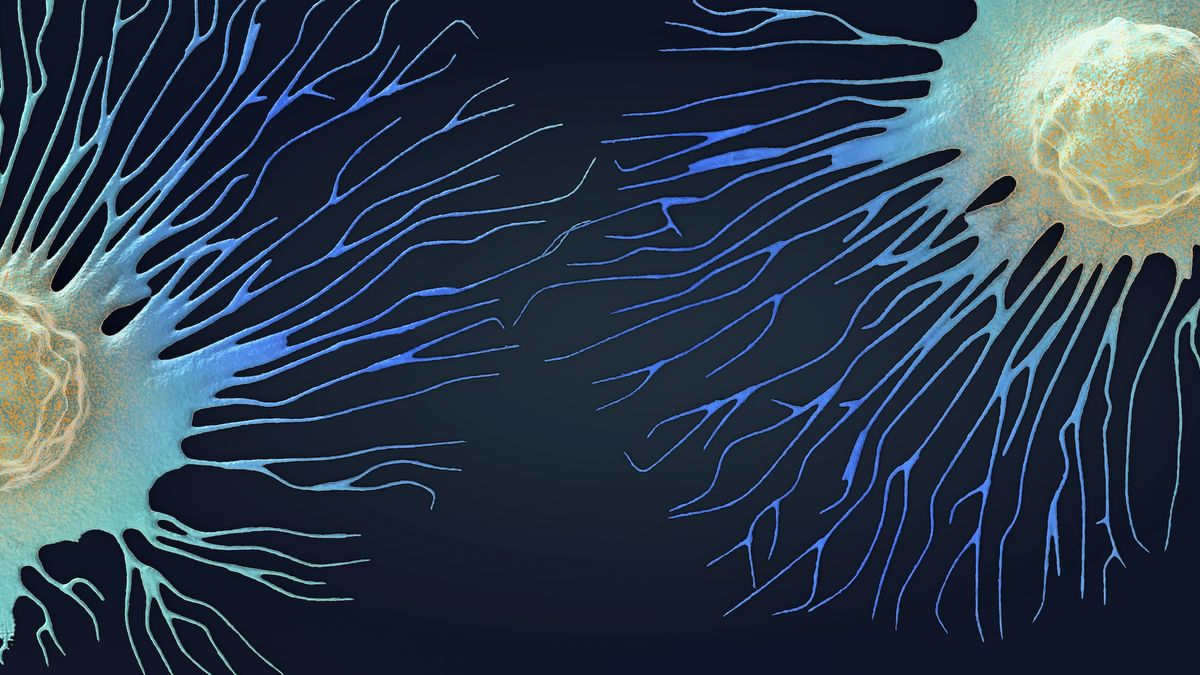

Circulating tumor cells — the cancer cells that break away from tumors and enter the bloodstream — play a key role in metastasis. These cells are more likely to form new tumors in other parts of the body when they cluster together, as opposed to when they travel alone.

Related: ‘I’ve never seen anything like this’: Scientists hijack cancer genes to turn tumors against themselves

Recent research in Switzerland identified existing drugs that could help break up these clusters. Experiments in mice showed that the drugs reduced the spread of breast cancer, suggesting a potential new approach to limiting metastasis. These drugs — known as Na+/K+ ATPase inhibitors — include digoxin and work by altering the flow of charged particles in and out of cells.

Building on their previous research, the scientists have now conducted a clinical trial to test whether digoxin could shrink clusters of circulating tumor cells in women with metastatic breast cancer. Based on their early results, published Jan. 24 in the journal Nature Medicine, the researchers think digoxin could someday complement other treatments aimed at fighting primary tumors, meaning cancers that have not yet spread.

First human study of digoxin in cancer

Digoxin is an old medication that was first derived from the foxglove plant (Digitalis lanata) in 1930. It’s used to treat heart failure and atrial fibrillation and works by blocking structures in heart cells called sodium-potassium pumps, which keep the levels of sodium and potassium inside cells in check. Blocking the pumps with digoxin leads to stronger contractions and a slower heart rate.

Now, scientists think this effect of digoxin could be leveraged for cancer treatment.

By inhibiting the sodium-potassium pumps in tumor cells, digoxin causes the cells to absorb more calcium. Previous research has shown that elevated calcium in cells can disrupt the formation of tight junctions and desmosomes — structures that help cells stick together. So digoxin likely weakens these connections between cancer cells that are clustering and causes them to break apart.

The team observed these effects in mice. To see whether digoxin could also disrupt tumor-cell clusters in human patients, they recruited nine women with metastatic breast cancer. The participants each had at least one circulating tumor cell cluster at the time they were screened.

During the study, the women took digoxin every day for seven days. To track the circulating tumor cells, the researchers collected blood samples from the participants before treatment, two hours after their first doses, and then again three and seven days into the study.

The size of the participants’ cancer-cell clusters shrank by an average of 2.2 cells per cluster after treatment, the researchers found. The average cluster contained four cells before treatment. No serious treatment side effects were reported.

Questions to answer

Although promising, the trial results have some limitations.

The shrinkage of tumor-cell clusters was statistically significant, but overall, the drug’s effect was quite small, Dr. Daniel Smit and Dr. Klaus Pantel, of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf in Germany, wrote in a commentary about the new study.

In theory, having fewer circulating clusters might reduce the chance of the cancer spreading even further, they said. But it likely would not stop existing secondary tumors from growing, they added. In other words, the drug would likely be useful only at a certain stage of cancer progression.

Smit and Pantel also pointed out that digoxin did not prevent circulating tumor cells from clustering with healthy blood cells — a process that also drives cancer spread. Furthermore, based on clinical studies by other groups, they argue that, while breaking up clusters may slow metastasis, tumor cells that are migrating on their own are also tied to negative effects.

Smit and Pantel also noted that patients with metastatic breast cancer have a range of clinical outcomes. “Therefore, an observation based on nine people with cancer is hypothesis-generating rather than fully conclusive,” they wrote.

Nonetheless, the trial hints that digoxin and similar drugs could have a place in cancer care. Now, the researchers plan to create new molecules based on digoxin that could more effectively break up circulating clusters. They are also conducting experiments to see whether digoxin could be applied to other types of cancer.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.