Scientists have finally solved the mystery of how the fossilized feathers of a 30,000-year-old vulture were preserved with such unprecedented levels of detail.

The griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus), which was initially uncovered in the Colli Albani volcanic complex southeast of Rome, Italy, in 1889, was found in incredibly good condition — it even had traces of its delicate wing feathers and eyelids.

Since the discovery, researchers have puzzled over how exactly the bird was so well-preserved. Now, in a new study published Tuesday (March 18) in the journal Geology, researchers suggest this rare preservation of such intricate details may be due to tiny silicon-rich crystals called zeolites that formed as the bird’s remains were buried in ash from an erupting volcano.

This would mark the first time that fossilized soft tissues, like feathers, have ever been found preserved in volcanic ash, the scientists said.

“Fossil feathers are usually preserved in ancient mudrocks laid down in lakes or lagoons. The fossil vulture is preserved in ash deposits, which is extremely unusual,” study lead author Valentina Rossi, a paleobiologist at University College Cork in Ireland, said in a statement.

“When analysing the fossil vulture plumage, we found ourselves in uncharted territory. These feathers are nothing like what we usually see in other fossils,” she added.

Rare preservation

This fossil was first found in the foothills of Italy’s Mount Tuscolo in 1889 by a local landowner. Paleontologists at the time noted the rare preservation of feathers in volcanic rock. However, over the years, much of the fossil was lost, with only the feathers of one wing and the bird’s head and neck remaining. In recent years, scientists have reanalyzed the fossil, revealing the intricate details of the vulture’s eyelids and skin.

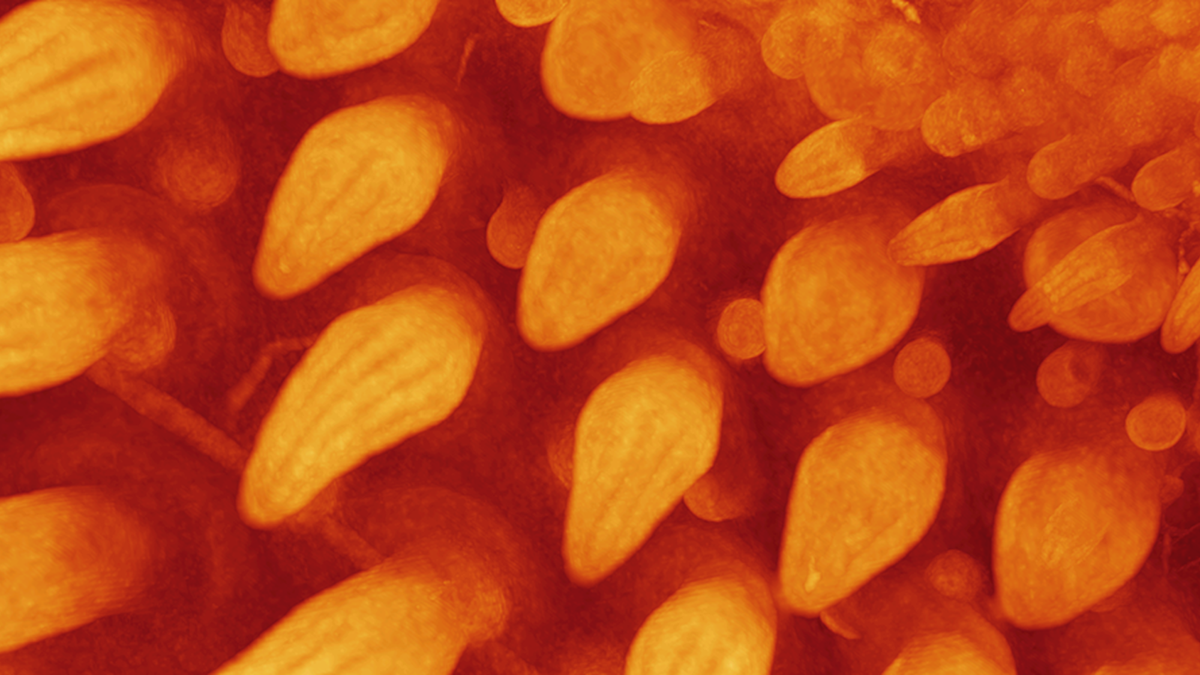

In the new study, the researchers used electron microscopes and chemical tests to study the fossilized feathers, which revealed that the fossils were preserved in three dimensions. This is very unusual for feathers, which usually only leave two-dimensional fossilized carbon imprints in rocks. Three-dimensional feathers have only ever previously been found in amber.

The researchers could see details of the feathers’ structures as small as one micron (0.001 millimeters), and discovered that the feather fossils were made of zeolite, a mineral that is often associated with volcanic environments.

“Zeolites are minerals rich in silicon and aluminium and are common in volcanic and hydrothermal geological settings,” Rossi said. “Zeolites can form as primary minerals (with pretty crystals) or can form secondarily, during the natural alteration of volcanic glass and ash.”

This discovery is the first time that feathers have been found preserved in such a way, and with such high levels of detail. Additionally, no other fossils have ever been discovered preserved in zeolite.

The fact that these feathers were preserved in zeolite indicates that the ancient vulture was likely buried in a huge cloud of volcanic ash, which was much cooler than the pyroclastic flows that scorched Pompeii during the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

“The fine preservation of the feather structures indicates that the vulture carcass was entombed in a low temperature pyroclastic deposit,” Rossi said.

This ash likely crystallized into zeolite after reacting with water over the course of a few days, with tiny crystals of the mineral gradually replacing every cell and detail of the bird’s remains.

“Volcanic deposits are associated with hot, fast-moving pyroclastic currents that will destroy soft tissues,” study co-author Dawid Iurino, an associate professor in vertebrate paleontology at the University of Milan, said in the statement. “However, these geological settings are complex and can include low temperature deposits that can preserve soft tissues at the cellular level.”

The researchers hope that this unique discovery could pave the way to finding other fossils hidden in volcanic rocks.

“The fossil record is continually surprising us, be it new fossil species, strange new body shapes, or in this case, new styles of fossil preservation. We never expected to find delicate tissues such as feathers preserved in a volcanic rock,” study co-author Maria McNamara, a professor of paleontology at University College Cork said in the statement.

“Discoveries such as these broaden the range of potential rock types where we can find fossils, even those preserving fragile soft tissues.”