On Tuesday (March 18) NASA astronauts Sunita Williams and Butch Wilmore are expected to splash harmlessly into Earth’s oceans inside a SpaceX crew capsule, ending a more than nine-month stay in space that was originally slated to last just a few weeks. When their capsule is finally opened, the astronauts will likely be carried out and loaded onto stretchers.

The reason for this has nothing to do with Williams and Wilmore’s specific mission aboard the International Space Station (ISS), but is simply a matter of protocol that all astronauts must follow, experts told Live Science.

When astronauts return to Earth from space, they can’t immediately walk upon landing. This is due to temporary changes to the body that occur in space — a fact that NASA addresses with strict safety procedures.

“A lot of them don’t want to be brought out on a stretcher, but they’re told they have to be,” John DeWitt, director of applied sports science at Rice University in Texas and a former senior scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center, where he developed methods to improve astronaut health during spaceflight, told Live Science.

“Space motion sickness”

Just like someone might experience motion sickness on a roller coaster or while riding in a boat on choppy waters, astronauts can experience dizziness and nausea when they return to Earth. Primarily for this reason, astronauts are typically rolled out on a stretcher after their landing as a precautionary measure, DeWitt said.

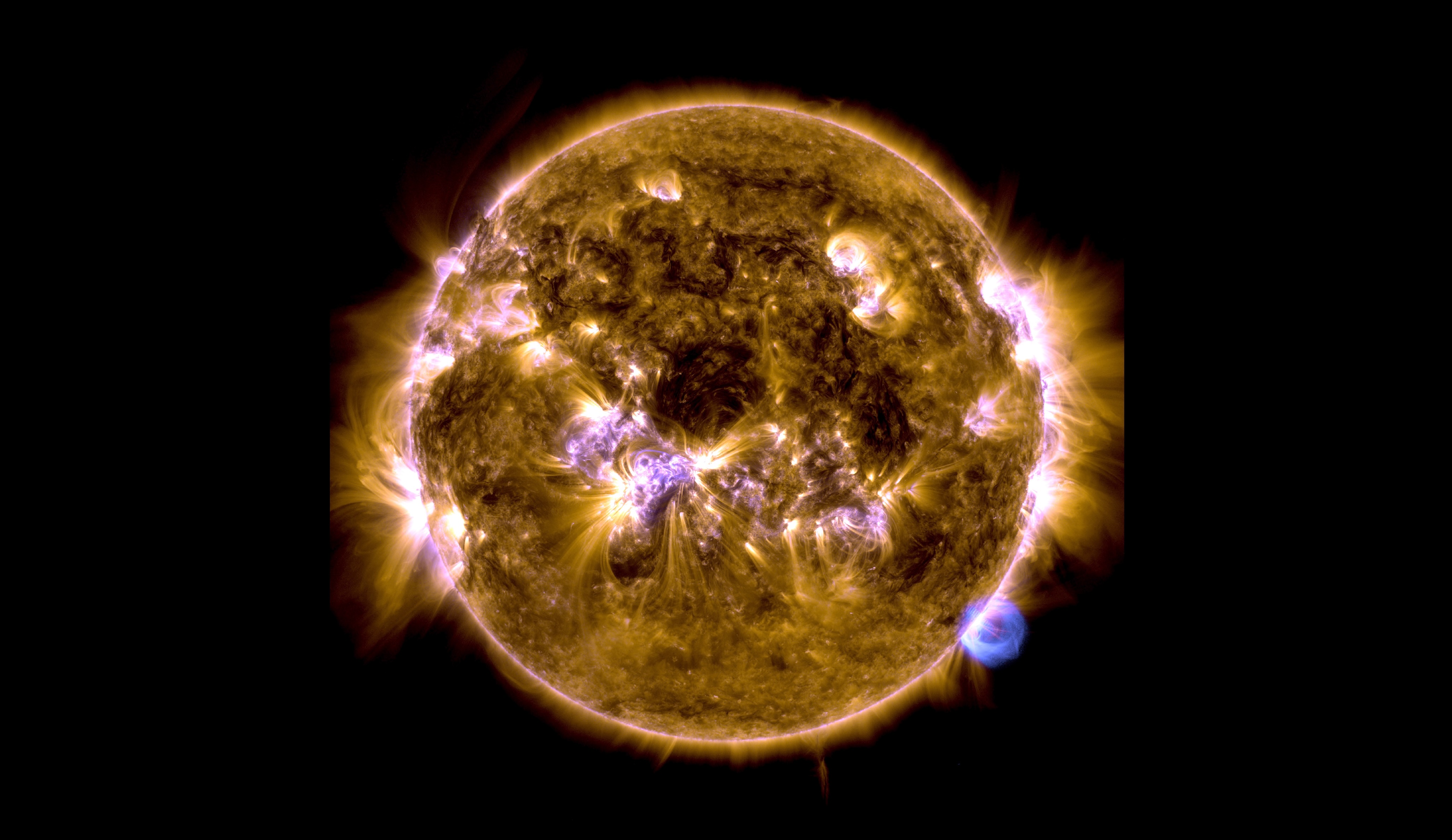

The temporary sensation occurs because our bodies are designed to take advantage of the constant force pulling us down here on Earth — gravity. However, orbital space habitats such as the ISS are in perpetual freefall toward our planet, which creates a feeling of weightlessness for the astronauts inside and prompts their bodies to adapt to the altered environment.

Related: Boeing Starliner astronauts spent nearly 300 days stuck in space — is that a new record?

One significant change occurs in the sensory vestibular system within the inner ear that’s crucial for maintaining balance, DeWitt said. In space, this system becomes accustomed to ignoring certain sensory inputs as the brain adjusts to weightlessness. So when astronauts return to Earth and gravity is reintroduced, they begin readjusting once again, which can temporarily cause “space motion sickness,” DeWitt said.

Another change astronauts experience, especially those who spend long durations in space, is gradual muscle and bone loss. While walking here on Earth is usually sufficient to keep our muscles strong due to gravity, astronauts in space don’t need to use their muscles as much. This lack of activity causes the muscles to weaken and shrink over time, leading to a condition known as muscle atrophy.

“We feel strong and ready”

To counteract these and other spaceflight-related effects, astronauts who spend extended periods in space — including Williams Wilmore — follow a thorough daily exercise regimen using a suite of equipment on board the station.

“Been working out for the past nine months,” Williams told Live Science via an email to DeWitt. “We feel strong and ready to tackle Earth’s gravity.”

Williams and Wilmore are part of the Crew-9 mission alongside NASA astronaut Nick Hague and Roscosmos cosmonaut Aleksandr Gorbunov, who are all slated to return to Earth aboard a SpaceX Dragon spacecraft on March 18. Their return will mark the end of an unexpected nine-month stay for Williams and Wilmore, after the Boeing Starliner capsule they launched on encountered several issues during its journey to the ISS, including thruster malfunctions and leaking propulsion, which led NASA to bring the spacecraft back to Earth empty.

Despite the setbacks, “They’re in good spirits and feel very confident that there’s not going to be any major issues because of being on the space station so long from a physiological perspective,” DeWitt said. “They’re getting exactly what they would have gotten had their trip been planned to be nine months.”

The effects of long-term spaceflight on the human body are an active area of research. Currently, Russian Cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov holds the record for the longest consecutive time in space having spent 437 days — just over 14 months — aboard the now-defunct Mir space station in 1994 and 1995.