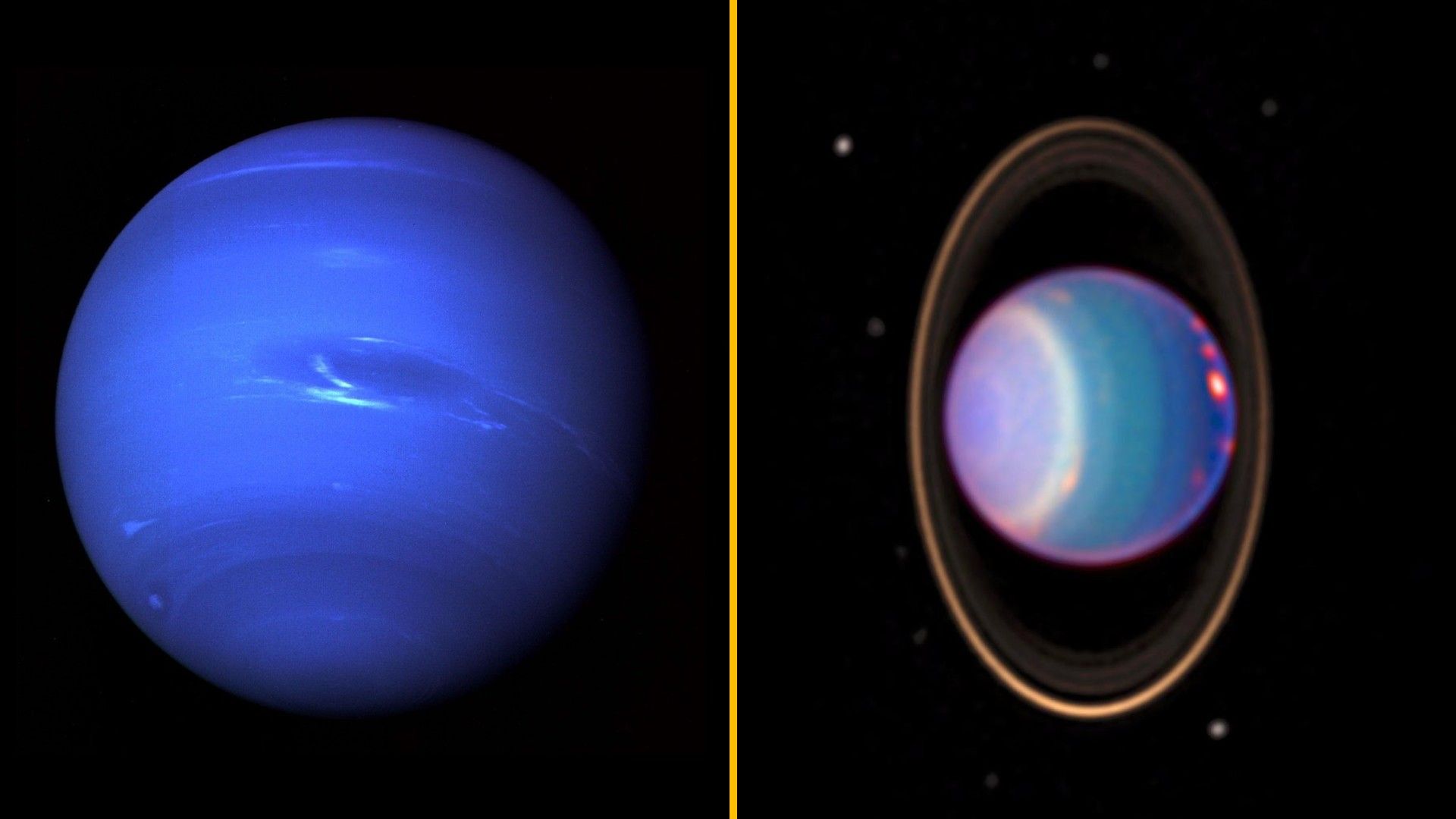

The interiors of Uranus and Neptune may be rockier than scientists previously thought, a new computational model suggests — challenging the idea that the planets should be called “ice giants.”

The new study, published Dec. 10 in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics, may also help to explain the planets’ puzzling magnetic fields.

Far out planets

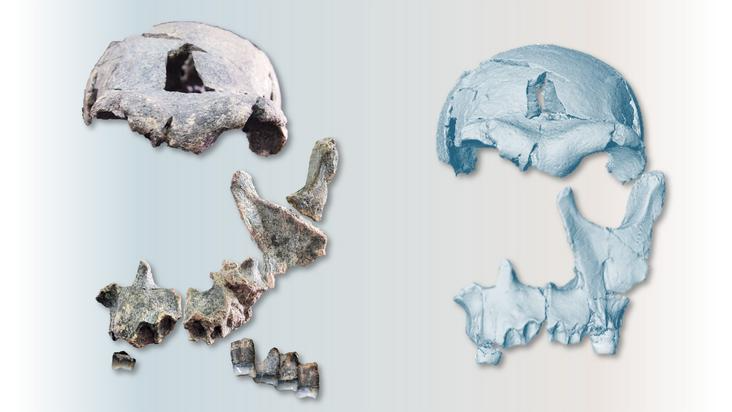

Morf and his supervisor, Ravit Helled, developed a new hybrid model in an attempt to better understand the interior of these cold planets. Models based on physics alone rely heavily on assumptions made by the modeler, while observational models can be too simplistic, Morf explained. “We combined both approaches to get interior models that are both unbiased and physically consistent,” he said.

The pair started by considering how the density of each planet’s core could vary with distance from the center of the planets and then adjusted the model to account for the planets’ gravities. From this, they inferred the temperature and composition of the core and generated a new density profile. The team inputted the new density parameters back into the model and iterated this process until the model core fully matched current observational data.

This method generated eight total possible cores for both Uranus and Neptune, three of which had high rock-to-water ratios. This shows that the interiors of Uranus and Neptune are not limited to ice, as previously thought, the researchers said.

All of the modeled cores had convective regions where pure water exists in its ionic phase. This is where extreme temperatures and pressures cause water molecules to break apart into charged protons (H+) and hydroxide ions (OH–). The team thinks such layers may be the source of the planets’ multiple magnetic fields, which cause Uranus and Neptune to have more than two poles. The model also suggests that Uranus’ magnetic field is generated closer to its center than Neptune’s is.

“One of the main issues is that physicists still barely understand how materials behave under the exotic conditions of [high] pressure and temperature found at the heart of a planet [and] this could impact our results,” Morf said. The team aims to improve their model by including other molecules, like methane and ammonia, which also may be found in the cores.

“Both Uranus and Neptune could be rock giants or ice giants depending on the model assumptions,” Helled said. She noted that much of our understanding of these planets may be incomplete, as it’s based largely on data collected by the Voyager 2 space probe in the 1980s.

“Current data is insufficient to distinguish the two, and we therefore need dedicated missions to Uranus and Neptune that can reveal their true nature,” Helled added

The team hopes the model may act as an unbiased tool for any new data from future space missions to these planets.