Scientists have created a new tool to watch plants breathe in real time. The new tech could help identify the genetic traits that make crops more resilient to global climate change, the researchers say.

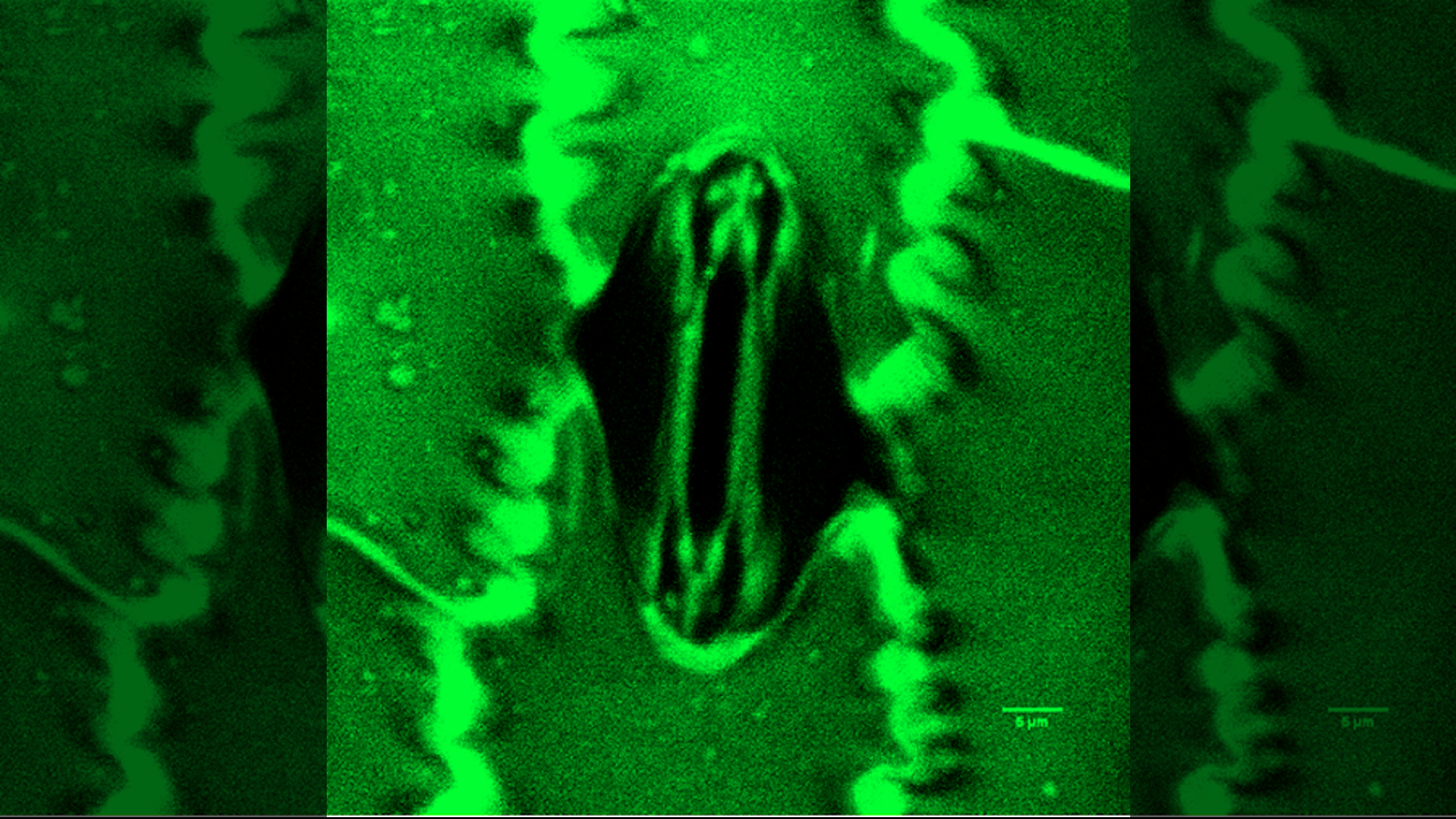

Humanity’s food system depends on tiny pores on plants’ leaves. These microscopic pores, called stomata (from the Greek word for mouth) regulate how much carbon dioxide a plant consumes and how much oxygen and water vapor it breathes out.

Specialized cells surround the pore openings, and they expand and contract to open and close the stomata. But scientists still don’t know exactly how individual stomata regulate what the plant moves in and out.

“Despite the fact that we have studied stomata for a very, very long time, and we do know a great deal about them, we really struggle to connect understanding the amount of these oxygen, water and carbon going in and out of the stomata with how many stomata there are, how big they are, and how they open,” Leakey said.

To understand this process better, researchers developed the Stomata In-Sight tool, which they described in a study published Nov. 17, 2025 in the journal Plant Physiology. The Stomata In-Sight instrument combines a microscope, a system to measure the stomatal gas flux, and machine-learning image analysis. “It measures the collective activity of thousands upon thousands of stomata in terms of these carbon dioxide and water fluxes,” Leakey said.

To use Stomata In-Sight, small pieces of leaf are placed in a climate-controlled chamber about the size of a human palm, which is connected to a gas exchange system, Leakey explained. Researchers can change the conditions inside the chamber to see how the stomata respond to variations in temperature, water availability and other parameters. The microscope sits outside the chamber, looking in, while the machine-learning analysis identifies stomata from the microscope’s images, speeding up analysis.

It has taken the team several years to develop the new tool. A major issue was that tiny vibrations — such as the fan in a gas-exchange system — can lead to blurry images. “This actually took us about five years, and we had probably three prototypes that failed when we got to the final solution,” Leakey said.

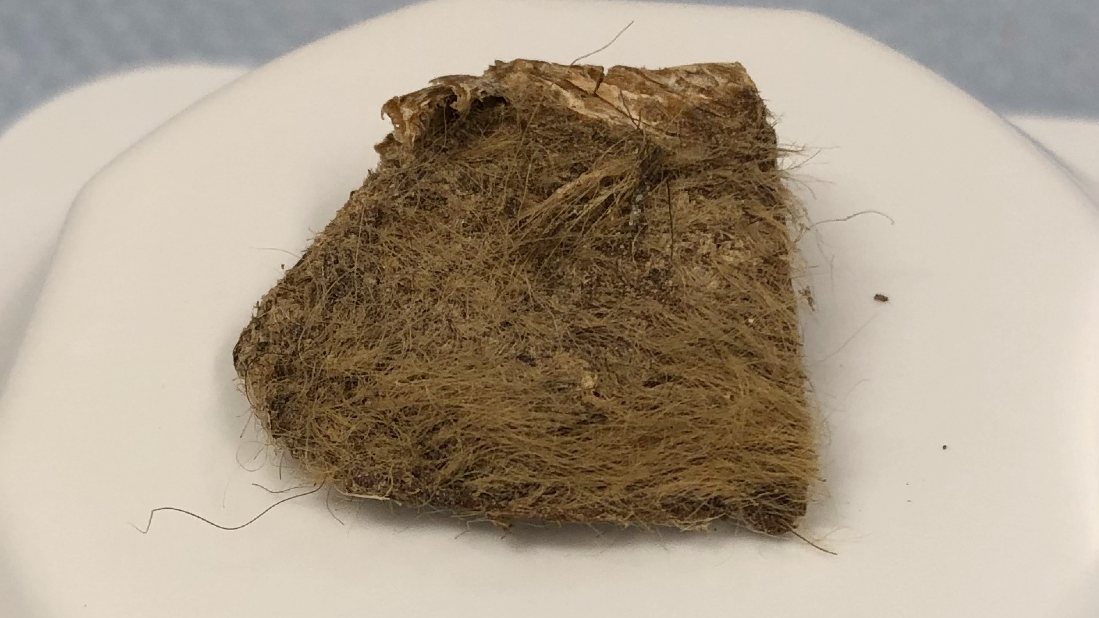

The team has already used the system to look at the stomata of maize (Zea mays) and other crops. It also used the insights about stomata to engineer sorghum (Sorghum bicolor, a type of plant cultivated for grain) to use less water. They identified the genes responsible for the density of stomata on sorghum leaves and engineered plants with more spread-out stomata.

The University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign has patented the technology, and while it is not commercially available, Leakey hopes that there may be companies interested in producing the instrument for other research groups.

Not all scientists are convinced, however. Alistair Hetherington, an emeritus professor of botany at the University of Bristol in the U.K., doubts that the new tool will revolutionize the study of stomata.

“We have been able to use conventional microscopy to measure changes in stomatal aperture for well over hundred years, confocal microscopy for probably 25 years, and the so-called gas exchange techniques for 50 years,” he told Live Science. The new study puts the techniques together, but researchers are likely to stick to “tried and tested existing techniques that deliver,” Hetherington added.

Nevertheless, Leakey is looking at improving the tool to broaden its usefulness. The main challenge at the moment is that watching the stomata “breathe” is very time consuming. “When you’re looking through the microscope, you see on average two to three stomata in the little piece of leaf you’re looking at,” he explained. “But you actually need to measure 40 or 50 stomata in order to account for the variation.” This has to be done manually.

Also, it can take a few minutes for stomata to respond to changing conditions. This means that scientists have to wait for the stomata to finish opening or closing before they take another image.

“It’s quite labour intensive, but it’s possible we could use robotics and artificial intelligence to turn it into a production-line process,” he said. “There’s a lot of excitement in the scientific community about how we can accelerate biological research using those sorts of tools.”