The online admonition to “touch grass” to soothe your emotional state may be backed by science — at least in lab mice.

A recent study finds that mice that live outside are less anxious than those that spend their days in safe, shoebox-sized cages. And that may highlight a fundamental flaw in laboratory research, including that used to test the safety and effectiveness of drugs eventually intended for people.

“Why is there that huge gap in results between the animal models in the labs and the real-life experiences when we test [many] drugs in humans?” said first study author Matthew Zipple, a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University “We think much of this effect may be explained by this really artificial, standardized environment in which lab animals are kept.”

The findings were published in December in the journal Current Biology.

Less anxious in the outdoors

Both wild mice and humans have rich social environments, and wild mice are constantly on the go, foraging, burrowing and facing risks, including the many predators that like to snack on them.

In comparison, lab mice sit in small cages with two or three same-sex siblings. There, food and water are delivered on a regular schedule. Studying medications in those mice may be akin to limiting research to prisoners in solitary confinement, Zipple told Live Science.

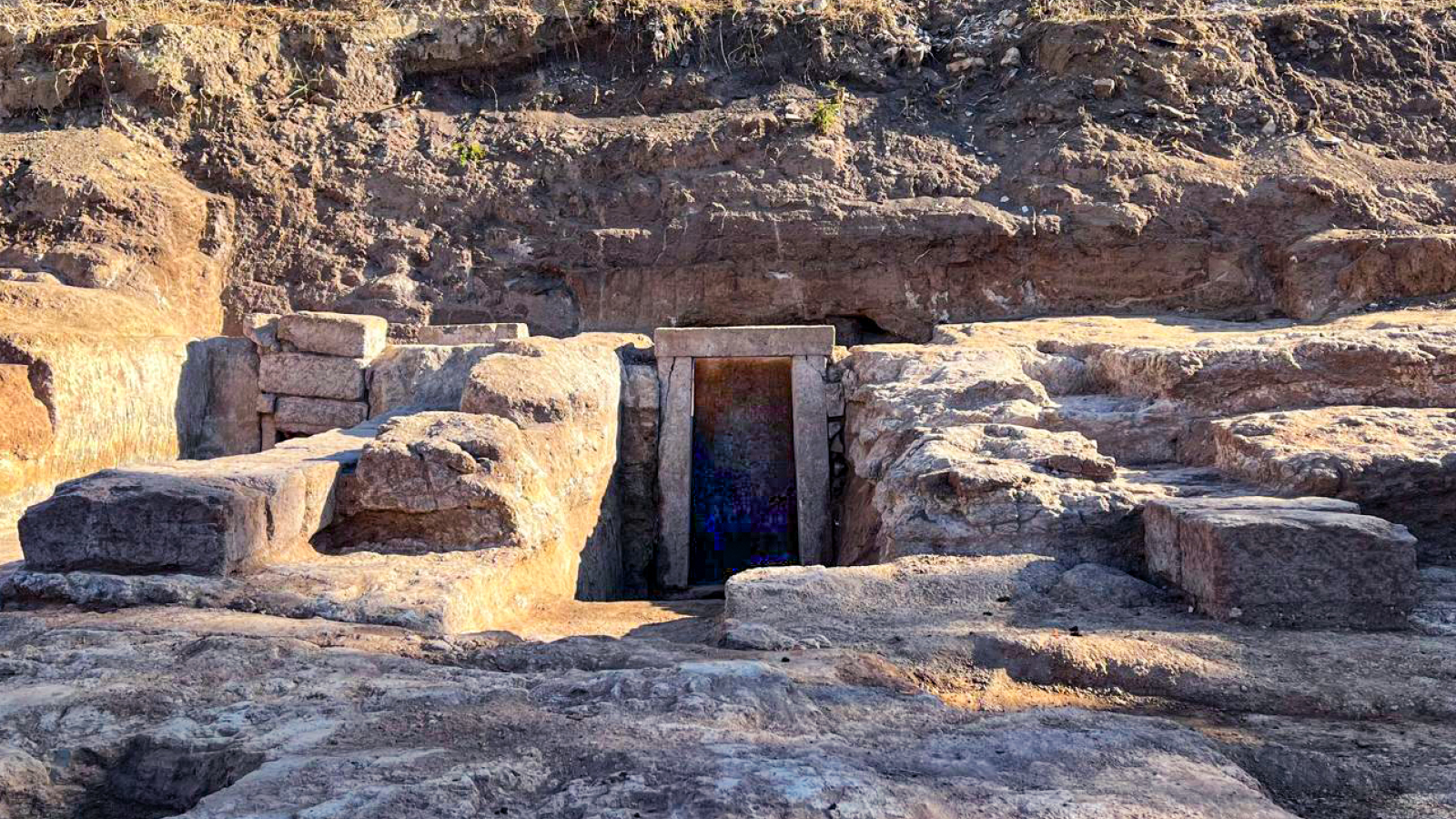

Zipple and his colleagues set out to compare the psychology of two groups of lab mice: a group that remained in a laboratory and a group that lived with other mice in an outdoor enclosure, complete with grass, dirt and exposure to the sky. They did so using a standard maze, called the “elevated plus maze,” which has two enclosed arms and two open, catwalk-style arms.

On their first exposure to this maze under bright lab lights, lab mice typically explore the open arms, find them terrifying, and basically never venture out on them again. Instead, they remain in the comparatively safe, enclosed portion of the maze. This reaction is so consistent that researchers use the open arms to induce and measure anxiety in lab mice.

But mice living in a wild-type environment weren’t freaked out by the open arms at all, Zipple and his team found. They spent just as much time exploring these areas on subsequent visits to the maze as they had the first time, all while under bright light.

Meanwhile, cage-dwelling mice that were sent to live outside also saw their maze anxiety evaporate; animals that already had demonstrated an apparent fear of the open arms and then spent a week outside subsequently spent twice as much time exploring the open arms compared with animals that kept living in cages.

The use of the standardized maze was a “very powerful way to show the limits of business as usual,” said Andrea Graham, an evolutionary ecologist at Princeton University who was not involved in the research.

Caged mice have other key differences

Graham’s lab has shown that mice that live in lab cages are also immunologically different from mice who live outside and encounter dirt, plants and large numbers of other mice. That matters, she said.

In one famous 2006 case, a medication called TGN1412 seemed to boost the immune system against leukemia in lab mice but caused a near-fatal immune reaction in the first six healthy human volunteers exposed to the drug. Subsequent research revealed that, in the lab mice, the medication activated immune cells that regulate and calm the immune response. However, in mice living in wild-type enclosures, the medication instead activated cells that ramp up the immune response to the point that the body attacked itself.

“If we restrict ourselves to only studying a couple of different genotypes [genetic profiles] of lab mouse in the same immunologically boring, psychologically boring environments, we’re not going to really be able to study the full spectrum of human immune or nervous system response to the environment,” Graham told Live Science.

Using wild-style enclosures requires some upfront cost and effort, and it also reduces the rigid control that’s placed on study animals in order to limit confounding variables in experiments. As such, they pull biomedical scientists out of their comfort zone, Zipple said.

But adding in tests of these less-confined mice could save a lot of effort and money on the human trials side by pinpointing the medications that are most likely to translate from the lab to the clinic, the study authors argue. Zipple and his colleagues are now looking at ways that caged and wild-living mice age differently.

“The broader goal is to make a list of biomedically relevant behaviors, phenotypes [observable traits] and psychological traits that look the same in the lab and the field,” he said, to help with the issue of translating results to humans. They also want to compile a “list of traits that look quite different,” he said.