Astronomers have solved the mystery of how some stars stay youthfully bright and blue, despite being almost as old as the universe itself: They cannibalize their stellar siblings.

Known as blue straggler stars, these age-defying celestial objects have mystified astronomers for more than 70 years. “Blue stragglers are anomalously massive core hydrogen-burning stars that, according to the theory of single star evolution, should not exist,” researchers wrote in a paper published Jan. 3 in the journal Nature Communications.

Searching for age-defying stars

Scientists previously posited that blue stragglers can form in two ways: through violent collisions between two stars, or through more subtle interactions in binary systems as pairs of stars orbit each other and trade gas.

The team found that the latter scenario is more likely.

Galactic globular clusters provide the perfect place to study stellar interactions between gas-siphoning binary systems. These spherical clusters contain thousands or millions of stars, held together by their collective gravity. With so many stars inhabiting a region only tens or hundreds of light-years across, clusters are among the most dense stellar environments in the cosmos. Therefore, they host many stellar collisions and plenty of binary systems.

Clusters are also incredibly ancient. “Their age is of the order of 12 [billion years], hence comparable to the age of the Universe,” which is 13.8 billion years old, Francesco Ferraro, lead author of the study and an astronomy professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, told Live Science via email. “In fact they are the oldest population in our Galaxy.” This means the single stars in each cluster hosting the blue stragglers formed at the epoch of galaxy formation.

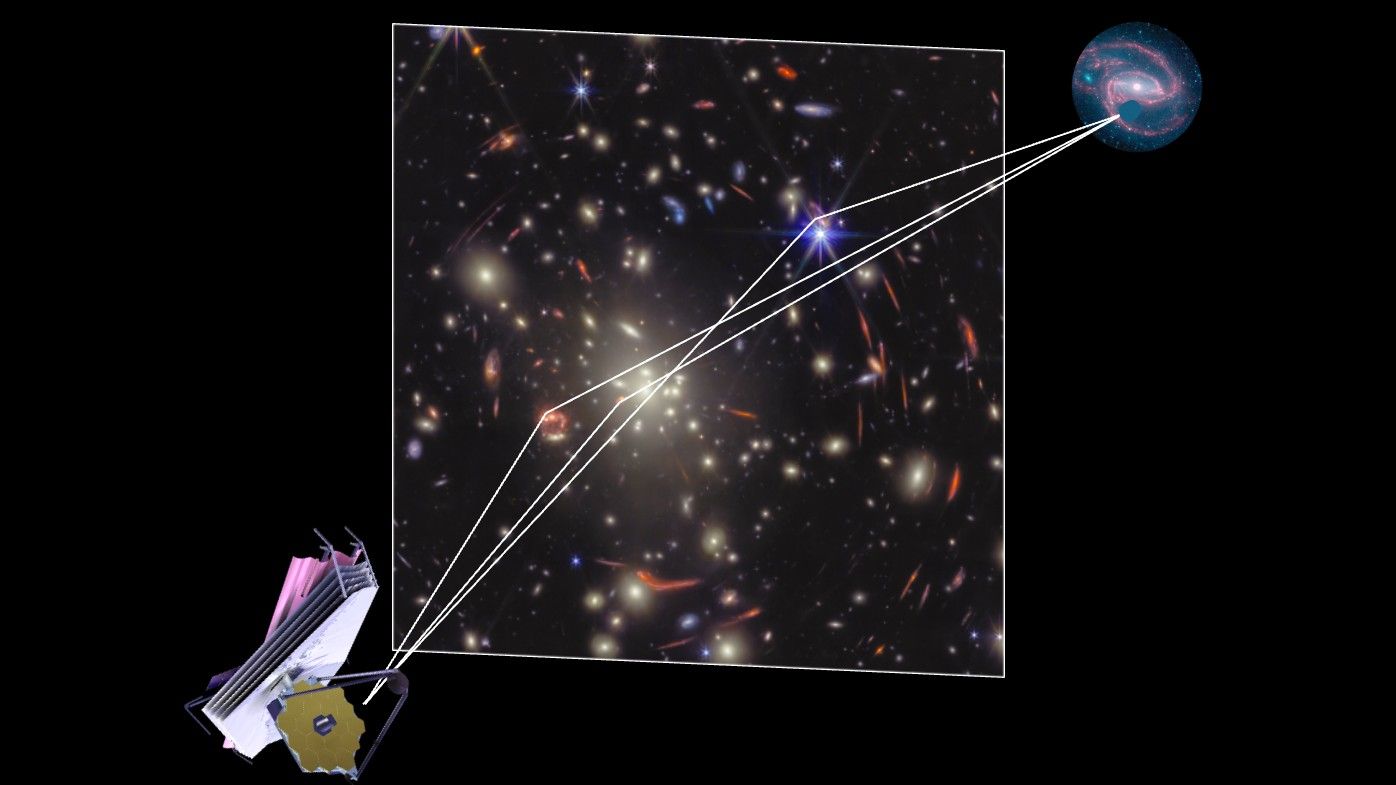

Older stars also emit different wavelengths of radiation. So the researchers utilized JWST’s ultraviolet filters to distinguish blue stragglers from their elderly cluster-mates — because hotter — younger stars emit more radiation at shorter wavelengths than older, redder populations that emit poorly in this part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

A surprising stellar scenario

Perhaps counterintuitively, the researchers found that blue stragglers are rarer in dense stellar environments, even though these regions are more likely to facilitate interactions between stars. Instead, stragglers are significantly more common in calm, low-density regions where stars are spaced farther apart and “fragile binary systems are more likely to survive.”

The researchers used an established, quantitative measure that relates the number of blue stragglers to the host cluster’s characteristics, like luminosity. This measure revealed that blue straggler populations vary greatly, from three to 58 blue stragglers per unit of luminosity — equivalent to the brightness of 10,000 suns. Accordingly, luminosity is related to a cluster’s overall mass and, therefore, its density.

Using that same measure, the researchers calculated that the number of regular stars in a cluster remains relatively constant. This suggests that stragglers and binary systems are especially sensitive to the density of their environments.

“Crowded star clusters are not a friendly place for stellar partnerships,” study co-author Enrico Vesperini, an astronomer at Indiana University, said in a statement. “Where space is tight, binaries can be more easily destroyed, and the stars lose their chance to stay young.”

Therefore, dense environments, such as those nearer the centers of clusters, may not be the stellar speed-dating venues they were assumed to be. The gravitational influences from large stellar populations create a cosmic-bumper-car-like effect that disrupts binary systems early in their evolution, before they can turn into blue straggler stars. As a result, the formation and survival efficiency of stragglers is 20 times higher in calmer, low-density environments, the researchers found.

A new way to understand stellar evolution

In addition to solving an astronomical mystery, this study offers a “new way to understand how stars evolve over billions of years,” study co-author Barbara Lanzoni, an astronomer at the University of Bologna, said in the statement.

But after billions of years, blue stragglers may not get to live out their quiet lives in peace. Because they are significantly more massive than their sibling stars, they are more likely to sink to the core of their clusters through a process called dynamical friction. Although this is unfortunate for these calm-loving stars, astronomers can then use them as a “dynamical clock” to extrapolate a cluster’s age based on the distribution of its blue stragglers.

Finally, these sprightly, fresh-faced stars highlight a dynamic stellar balance. Had they been born more massive, they would have died long ago as supernovas or white dwarfs. Their modest size, below 0.8 solar masses, have allowed them to survive long enough to renew their lifespans — at the cost of consuming their siblings.