Like a ship sailing through changing weather at sea, our solar system‘s journey around the center of the Milky Way takes it through varying galactic environments — and one of them may have had a lasting impact on Earth’s climate, a new study suggests.

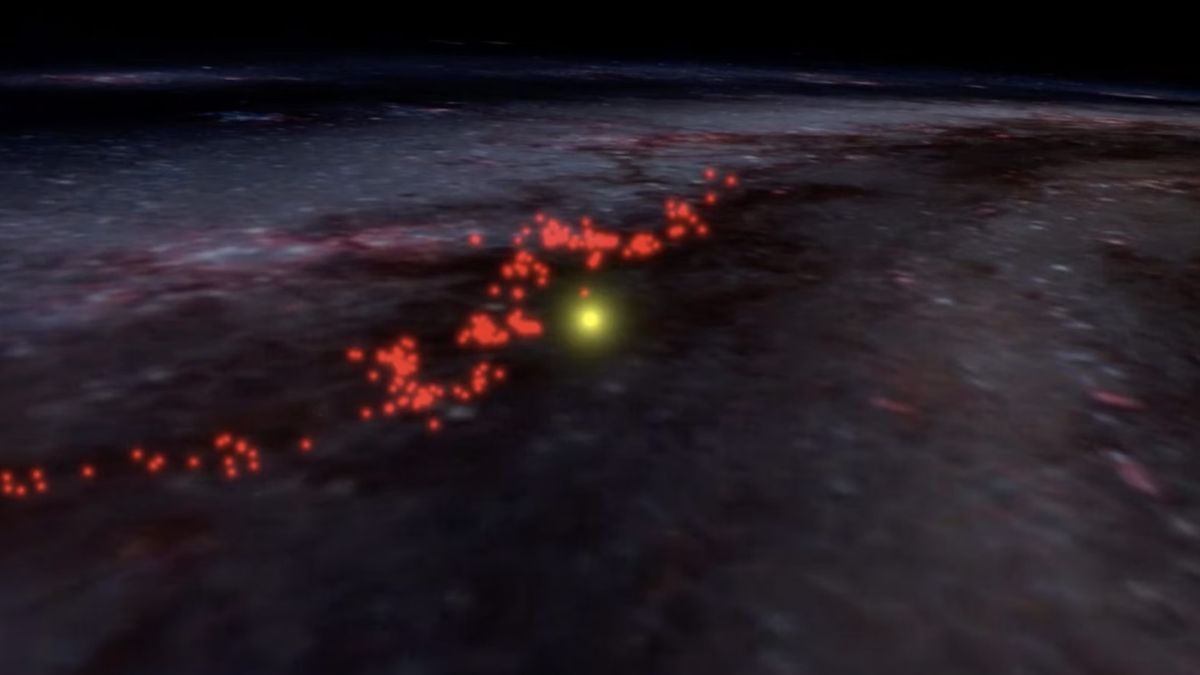

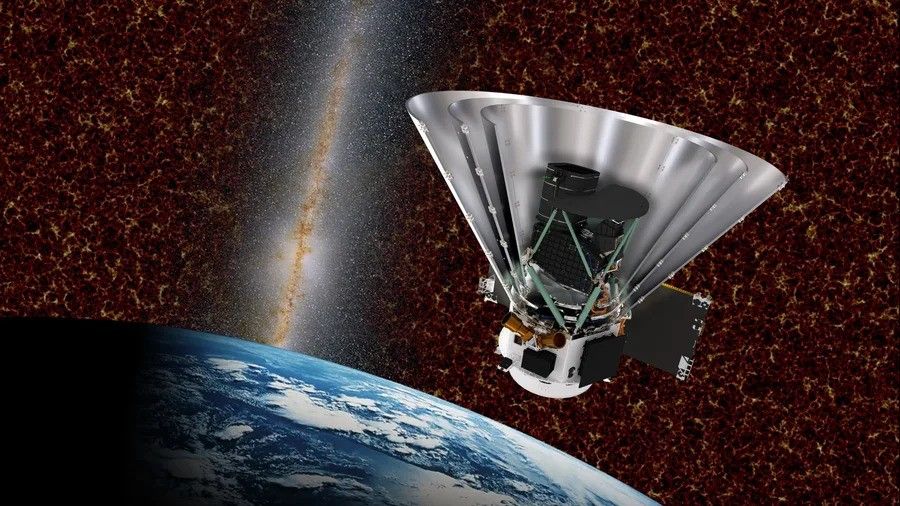

Observations from the European Space Agency‘s recently retired Gaia mission indicate that around 14 million years ago, our solar system passed through a dense, star-forming region in the direction of the constellation Orion. This region is part of a vast network of star clusters that spans nearly 9,000 light-years and is sculpted into a structure that astronomers have dubbed the Radcliffe Wave in honor of the Harvard Radcliffe Institute in Massachusetts, where the wave’s existence was confirmed.

When our solar system swirled through this structure millions of years ago, it may have received an increased flow of interstellar dust. The timing of this event aligns with Earth’s transition from a warmer to a cooler climate, as reflected in the expansion of the Antarctic Ice Sheet. This raises the possibility that the encounter could have contributed to that climatic shift in concert with several other factors and ongoing processes, the new study posits.

Further research may be able to test this theory. If unusually high abundances of radioactive elements — which are expected from such substantial dust influx — are indeed ever spotted in our planet’s geological record, it would strengthen the study’s hypothesis, “because you would have a geological signature and an astronomical perspective that can explain it,” study lead author Efrem Maconi, a doctoral student in astrophysics at the University of Vienna, told Live Science.

He and his colleagues described the findings in a paper published last month in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. However, spotting the crucial evidence in our planet’s geological record — a 14-million-year-old spike in the abundance of a rare iron isotope called iron-60, which is commonly released by supernovas but extremely rare on Earth — will not be easy.

“Looking back in time is hard — no matter if you’re doing it in space or Antarctica,” Teddy Kareta, an astronomer at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona who was not involved with the new research, told Live Science. “This is a really exciting scenario they’ve hypothesized, but finding concrete evidence for it mattering for the Earth’s climate, or even assessing the increase in dust flux that the solar system experienced, might take quite a bit of time and quite a bit of work from across the sciences.”

“We are really talking about yesterday”

Even though the Radcliffe Wave resides in our galactic backyard, at just 400 light-years away, astronomers just noticed it in 2020 thanks to the Gaia telescope’s ability to pinpoint the distances and velocities of known star-forming gas clouds, which allowed astronomers to create a 3D map of the solar neighborhood.

Related: 32 alien planets that really exist

Using Gaia’s most recent data, Maconi and his colleagues simulated the journey of 56 young star clusters associated with the Radcliffe Wave, tracing both their current orbits in the Milky Way and their pre-birth trajectories, which were inferred from their natal molecular clouds. This allowed the researchers to essentially “go back in time and see where they were in the past in relation to the solar system,” Maconi said.

The researchers found that our solar system was at its closest point to the Orion region around 14 million years ago, approaching within 65 light-years of at least two local, dust-heavy star clusters: NGC 1980 and NGC 1981. At the time, our solar system was largely as it is today; Earth and the other planets had been formed for more than 4 billion years. Yet, in cosmic terms, “we are really talking about yesterday,” Maconi said.

The simulations suggest that our solar system spent roughly 1 million years within this dense region, coinciding with our planet’s “Middle Miocene” transition from a warmer to a cooler climate. That points to the possibility that substantial interstellar dust could have blocked some of the sun’s radiation, thereby accelerating the planet-wide cooling, the new study posits.

“It’s a big claim to suggest galactic influences on the climate of the Earth,” Kareta said. But “the agreement in timing between both events should certainly motivate astronomers and geologists alike to try to assess the likelihood of this scenario in more depth.”

There is “reasonable evidence to believe that Earth’s voyage around the Milky Way influenced its geology,” Chris Kirkland, a geologist at Curtin University in Australia who was not involved with the new study, told Live Science.

For instance, previous research led by Kirkland suggested frequent, high-energy impacts from meteorites during Earth’s youth contributed to the production of continental crust on Earth. Kirkland declined to comment on the idea that extraterrestrial dust — as opposed to impacts — may have influenced Earth’s climate, however.

In the new study, Maconi and his team noted that the extraterrestrial dust reaching Earth would need to spike by at least six orders of magnitude higher than present-day levels to fully account for planet-scale climate effects. More subtle, indirect influences were more likely at play, and these effects would have unfolded over hundreds of thousands of years, setting them apart from current, human-driven climate change, Maconi said.

Even these differences are difficult to decipher, however, primarily because the geological record for the telltale iron-60 isotope stops at around 10 million years ago. Moreover, iron-60 is unstable, with a half-life of about 2.6 million years, making it especially challenging to detect a signal from an event that occurred 14 million years ago.

“The challenges in peering far back into the history of the Earth’s climate clearly limit our ability to assess the likelihood that the Radcliffe Wave had climatological effects at present,” Kareta said, “but advances in instrumentation and analysis techniques will likely facilitate us doing better in the future.”

There may be other places in our solar system that, unlike Earth’s landscape-recycling geological processes, might preserve either the dust itself or the telltale spike of extraterrestrial radioactive elements, Kareta added. These could include deep craters on the moon, specifically near its poles, which receive no sunlight throughout the year and should, in principle, stay cold and stable over long timescales, he said.

“Solar-system-wide processes ought to have left solar-system-wide evidence,” Kareta said.