This article is being co-published with The Lever, an investigative newsroom. Click here to get The Lever’s free newsletter.

One recurring theme in political satire is the fear that humans gravitate to oversimplified explanations for complex problems — a supposed curse of dumbing down that leads us to erect idiocracies led by the world’s Donald Trumps. But there’s an equally strong argument that this grand unifying theory is exactly wrong. Lately it seems we’re gaslit by overly complex explanations that end up obscuring simple realities.

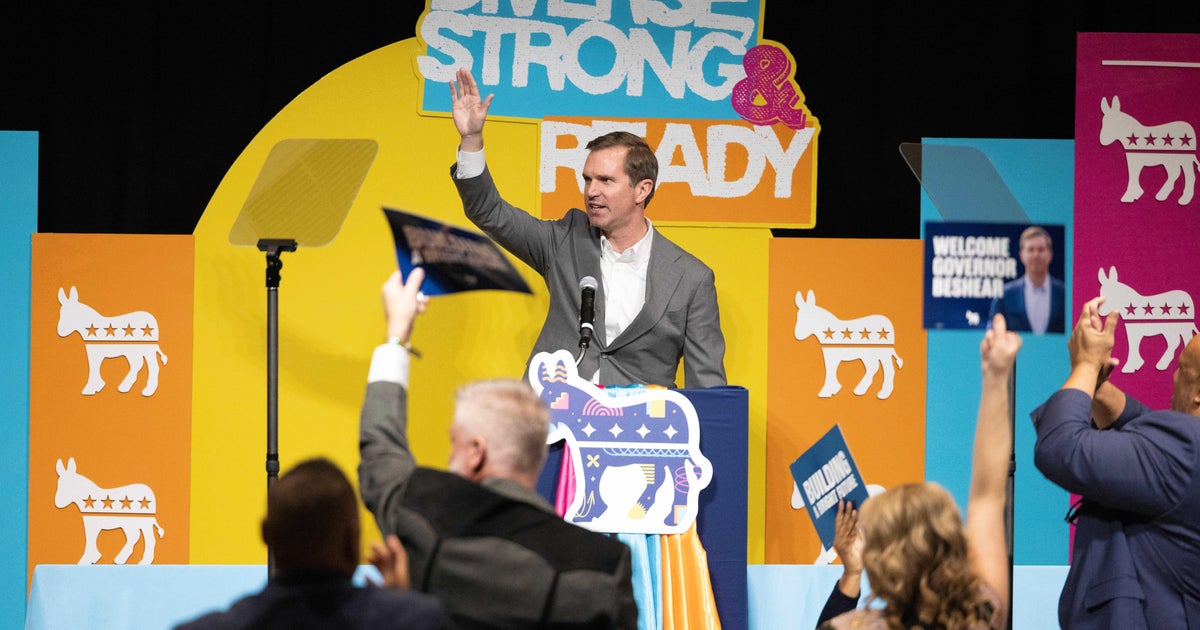

Take the 2024 presidential campaign. After the election, the internet teemed with Rube-Goldberg-machine theories about why the results were what they were. Democrats moved too far left! It was the culture war! It was a refusal to go populist!

The latter two were certainly salient — but rarely was the focus on the most decisive factor: the candidates themselves.

Indeed, lost in much of the prognostication was an indisputable fact: A political party cannot make a compelling sales pitch when its chief salespeople are a sundowning octogenarian and a deer-in-the-headlights successor.

We didn’t hear much about that because there’s a bias against straightforward explanations in the information economy. Shapers of the discourse — journalists, pundits, politicians, social media influencers — have built businesses and brands convincing us to forget Occam’s razor and embrace ever more elaborate explanations that only their self-purported genius can supposedly provide. They are Charlie Day at the bulletin board selling audiences the sensation of smartness and superiority, and then prompt more of the real objective: not revelation, but monetizable engagement.

Simple answers do the opposite. They are intuitive and therefore can’t be mined for clicks and likes. They elicit eyeroll emojis and “Captain Obvious” jokes. “Democrats lost because they nominated zombies” is the kind of truth that ends rather than prompts engagement. Simple now means “simpleton,” and the exegesis for everything is “it’s complicated,” even if it isn’t.

This Complexity Bias isn’t just annoying. It’s destructive. In our politics, it has become a form of misinformation, focusing our attention on noisy content rather than on simple explanations — and solutions.

The Kids Are Not Alright

Consider the recent viral panic about the decline of “conscientiousness,” “agreeableness,” and “extroversion” among young people — a trending narrative fueled by a Financial Times story that declared “smartphones and streaming services seem likely culprits.” That provocative conclusion — giving readers that “a-ha!” sense of revelation — was constructed to generate maximum engagement. On that score, mission accomplished.

There is no doubt screen ubiquity and social media addiction are exacerbating mental health crises. We’re inside a grand experiment subjecting millions of brains to a toxic brew of FOMO living-my-best-life content and go-fuck-yourself feedback. That is terrible for kids — and limiting their phone use is a great idea.

But are phones really the primary driver of these anti-social trends? It’s a fairly complicated hypothesis theorizing that screens expose young people to more upsetting news and negative commentary than they’ve been exposed to in the past, which then makes them sad, which then makes them less conscientious, agreeable, and outspoken.

That’s a helluva lot of bank shots. Could there be a simpler hypothesis for the decline in positive attitudes and prosocial behavior among this cohort?

What about the fact that younger Americans have been living through a shitshow in the offline world, now culminating in a cost-of-living crisis? What about the likelihood that in the post-Citizens United era, many of them have concluded that democracy is already dead, that they have little agency, and that civic participation and extroversion are pointless?

What about those Occam’s razor explanations?

Think about it: A 27-year old American man lived through a stolen presidential election, 9/11, the Iraq War, a financial crisis, mass foreclosures, an opioid epidemic, the explosion of economic inequality, the rise of Trump, a pandemic, the doubling of college costs, the tripling of health care costs, and now the return of Trump, a brutal job market, an affordability crisis, and skyrocketing death rates among his contemporaries.

This dude has been loaded up with debt, priced out of housing, and left scrounging for a bullshit job that will barely pay him enough to survive and yet locks him into indentured servitude for fear of losing his meager subsistence benefits (if he’s lucky enough to even have them).

And when he’s tried to engage in elections or the democratic discourse to demand political change, he’s been slandered as a freak, a charlatan, or a “Bernie Bro” as every election of his lifetime has been purchased by the oligarchs endlessly kicking him and his generation in the face.

So ask yourself again: Is the decline of conscientiousness, agreeableness, and extroversion the counterintuitive consequence of screens and streaming services altering neural pathways in complicated ways? That theory makes for spicy tweets, Instagram reels, blog posts, talk radio segments, and podcast discursions — but is it really the central explanation?

Or do those trends actually reflect something simple and boring: Namely, that for young people, reality bites way more than it ever has? And if that is what’s going on, then shouldn’t the frame be broader than smartphones and streaming? Shouldn’t the discourse be homing in on demanding the necessary financial resources to make things a little bit easier for younger generations?

But that’s the rub. “Necessary financial resources” is a euphemism for everything from student debt relief to universal health care to cheaper housing to every other investment that would improve young people’s lives. These are all things the world’s richest country can easily afford, but our society’s owners do not want to pony up for.

And so those owners’ media and algorithms cast simple solutions requiring oligarch sacrifice as the domain of the stupid. We’re given shiny-but-narrow self-help theories (limit screen time!) and bank-shot remedies (more mental health counseling!) but almost nothing that addresses the most obvious problem of all: a whole generation being denied resources and political power.

An Abundance Of Complexity

By now, whole media empires have been built to wonk-splain that everything is complex and not what it seems. From the Freakonomics brand to the Substack colossus to the “explainer” journalism oeuvre, it’s an entire “well, actually” economy, minting hot-take millionaires shrouding ideology in the veneer of empiricism.

“(It is) a certain style of politics that has dominated the Democratic Party and its ancillary media for fifteen years,” writes UC Berkeley historian Trevor Jackson. “It is an urban, affluent, and educated political outlook, one that is conflict averse, self-consciously ‘smart,’ and enthused about ‘complexity,’ but with specific meanings for both of those words — where smart conveys a certainty of opinion and the speed of its expression, and complexity means a grasp of the arcane self-referential rules and vocabulary of policy and economics.”

Once you understand the scope of this Complexity Bias — and how it is leveraged against plutocrat-hostile policies — it becomes difficult not to see it everywhere.

Look at health care. More and more Americans cannot afford medical care as our life expectancies decline. This is happening to us in a world where other industrialized countries long ago built straightforward universal health care systems that have fostered longer life spans. And yet thanks to America’s corporate-controlled discourse and its complexity bias, we remain trapped in interminable political conflict and commentary insisting that subsidies, tax credits, market reforms, and paperwork regimes are the solution — rather than just expanding existing public health care systems.

Today, something as straightforward as lowering the Medicare age is eyerolled by pundits droning on about Affordable Care Act marketplace tweaks — all to the applause of liberal news consumers, whose cherished media outlets have taught them that complexity rather than simplicity is the hallmark of intellect.

It’s the same Complexity Bias for Big Tech’s product du jour: artificial intelligence. The systems are indeed complicated — so complicated that their engineers all but admit they’re not sure they can control them. But Silicon Valley evangelists cite that complexity to claim that lawmakers cannot possibly come up with simple, workable regulations to prevent AI from medically bankrupting us, pricing us out of housing, denying us basic services, depleting natural resources, and killing the entire human species. (And any lawmakers who aims to regulate AI will soon be spent into the ground by the tech industry’s newest Super PAC).

The Complexity Bias also obscures our thinking about the economy as a whole.

We’re living in a new Gilded Age of crushing inequality blaring at us via social media’s wealth porn. It is an era of real estate moguls price-gouging renters and monopolies using market power to jack up prices and inflate profits. It is an epoch when oligarchs exploit workers and use their winnings to build gigayachts that The New Yorker identifies as “the most expensive objects that our species has ever figured out how to own.”

The obvious and simple-to-understand problem is oligarchy and concentrated corporate power. And yet we’re now drowning in “abundance” agitprop insisting it’s more complex than that. After $79 trillion was stolen from the bottom 90 percent of households, newfangled neoliberals are telling us that the problem is government, rather than their paymasters hoarding all the wealth. They tell us the fixes cannot be simple stuff like rent control, public housing investment, antitrust enforcement, higher taxes on the wealthy, anti-price-gouging initiatives, or making sure the indigent at least have a little bit of cash to survive.

We’re subjected to media misinformation omitting the most simple explanation — corporate profiteering — from inflation coverage.

We’re treated to screeds attacking unions, which have proven to be the most straightforward tool to combat inequality.

We’re given Substack “arguments” insinuating that simply giving poor people money doesn’t help them very much (of course it does).

We’re hit with a whole astroturfing campaign telling us that complex deregulation schemes are not corrupt plots to further enrich a handful of tycoons, but are instead three-dimensional chess moves that will unleash bighearted oligarch-altruists to eventually share their wealth… at some undefined point in the distant future.

Even the pithiest of abundance’s deregulatory initiatives are predicated on wildly complex —and wholly theoretical — chain reactions of events before anyone other than oligarchs would see real material benefit.

Take zoning reform. Abundists prophesize that getting rid of restrictive building rules would encourage more home construction, which would theoretically increase home supply, which would then theoretically reduce housing prices, which would then theoretically alleviate housing costs for some working-class buyers who will theoretically be able to outbid voracious institutional investors because… reasons. That’s lot of theoreticals and magical thinking.

Abundists nonetheless suggest this intricate game of real estate Plinko — which will quickly enrich wealthy developers — is somehow better than simply repealing an old Republican law preventing governments from just building tons of new housing right now.

We’re asked to accept these claims because they are wrapped in the veneer of media credentials and fancy Washington conferences bankrolled by far-right donors. And we’re told to pay no attention to the data showing zoning reforms — while laudable on their individual merits — have already spectacularly failed to transform housing markets where they’ve happened.

Complex Theories About Trump’s Simple Ascent

This pernicious Complexity Bias is now making the jump out of the policy realm and into our understanding of politics — and in particular, Trump.

The last decade has produced terabytes of speculation, commentary, and prognostication offering evermore convoluted theories about race, gender, and culture — all purporting to explain how a reality-TV huckster won the world’s most powerful office.

The simplest explanation of Trump’s rise still has little purchase, even as it is the most self-evident: Wall Street and its owned politicians created a financial crisis that destroyed millions of families, the incumbent party turned its populist promises of hope and change into more of the same corporate fealty that caused the emergency, and Americans (including in Barack Obama-supporting counties) then voted for a human bomb to blow up the system (and they later voted for him again when they perceived the Democratic president to be a Walking Dead extra).

This simple analysis can’t be discussed in polite company because the solution — resurrecting a Democratic Party that actually helps the working class — is too boring for cable TV news roundtables, too mundane for online virality, and too obvious to generate smug feelings of superior intelligence among news consumers. Most importantly, it’s also too offensive to the moguls who own the party, the media, and the algorithms.

Even the ascendant “democracy crisis” discourse is a victim of this Complexity Bias. The internet is producing metric tons of commentary, TikTok rants, and Pod Save America episodes telling us the solution to this moment’s authoritarianism and corruption is some convoluted agglomeration of lawfare, consultant-enriching election “infrastructure,” celebrified grassroots fundraising, and dark-money-financed media.

Just wrap this convoluted blueprint around the rotting husk of the Democratic Party, and somehow — magically! — democracy will gasp back to life… right?

Left out of the conversation are more simple, straightforward initiatives to alter the system. For example, using Democrats’ existing power in states and cities to create public campaign financing systems so that every election does not continue to be sold off to the highest bidder.

But that kind of solution is apparently too simple, too soporific — and too disempowering of the donor class — to center in the discourse, even as it recently transformed the politics of America’s largest city almost overnight.

The Simple Answer Is Usually The Correct One

Of course, opportunists do weaponize facile explanations to trick us — and some problems are exacerbated by genuinely complex, difficult-to-detect factors operating in the shadows.

Recall that during the financial crisis, conservative opportunists pretended the simple repeal of antidiscrimination laws would have protected us (that’s wrong), while few noticed that Biden’s byzantine bankruptcy legislation was quietly fueling the foreclosure crisis.

Fifteen years later, politicians and pundits alleged that the simple laws of supply and demand proved that pandemic aid was the primary driver of inflation (it wasn’t), all while corporate profiteering and the breakdown of the world’s complex supply chains were the underlying problems.

But in general, Occam’s razor usually applies — more often than not, actions and consequences are less complicated and more intuitive than we’re led to believe. Typically, the cause-and-effect of policy tracks what happened during the pandemic: When the government gave the working class money, more people were able to survive, and when those resources were cut off, disaster ensued.

Politicians and media worked around the clock to pretend it couldn’t possibly be that simple — after all, they had social media explainers to post and snarky “greedflation” screeds to pump out. Their Complexity Bias won the day, convincing lawmakers to terminate the aid for good, throwing millions of families back into poverty.

I wish there were a singular cure for this endless gaslighting, some corrective that could root the Complexity Bias out of the political conversation. But there isn’t.

The only solution is becoming aware that you are immersed in the Complexity Bias all the time — and realizing that overly convoluted explanations and prescriptions aren’t a sign of political superintelligence. They are often a signal of deception or ignorance.

“Simple can be harder than complex,” Apple cofounder Steve Jobs once said. “You have to work hard to get your thinking clean to make it simple.”

So the next time you see politicians or influencers peddling some complex theory about what seems like a straightforward problem, pause and remember that the simplest explanation is often the right one.

And keep in mind: Just because you’re paranoid about being manipulated doesn’t mean they aren’t trying to manipulate you.

More from Rolling Stone

Best of Rolling Stone

Sign up for RollingStone’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.