By disrupting a key gene, scientists made chicken feathers more dinosaur-like — but the results didn’t last.

In a new study, researchers inhibited a gene during embryonic development to make chicken feathers more primitive, like the kind of simple tube-shaped proto-feathers that likely first emerged in the ancestors of dinosaurs in the Early Triassic 250 million years ago.

They succeeded — but only temporarily. The chickens showed delayed feather development and naked spots at hatching, but within a few weeks, their plumage looked like any other fowl’s.

The study is part of a broader effort to learn how and why feathers first evolved. Researchers had previously altered the same gene to turn scaly chicken feet feathery, but turning back the clock on feather evolution proved harder.

“Our experiments show that while a transient disturbance in the development of foot scales can permanently turn them into feathers, it is much harder to permanently disrupt feather development itself,” study senior author Michel Milinkovitch, a professor of genetics and evolution at the University of Geneva, said in a statement. “Clearly, over the course of evolution, the network of interacting genes has become extremely robust, ensuring the proper development of feathers even under substantial genetic or environmental perturbations.”

Related: Dark regions of the genome may drive the evolution of new species

Just because the researchers didn’t make permanently dino-feathered chickens, it doesn’t mean the study was a failure. Milinkovitch and his co-author Rory Cooper, now a research fellow at the University of Sheffield in the U.K., showed how a particular gene, the whimsically named “Sonic Hedgehog” gene, is important in feather evolution. By disturbing this gene, the researchers were able to temporarily disrupt feather formation.

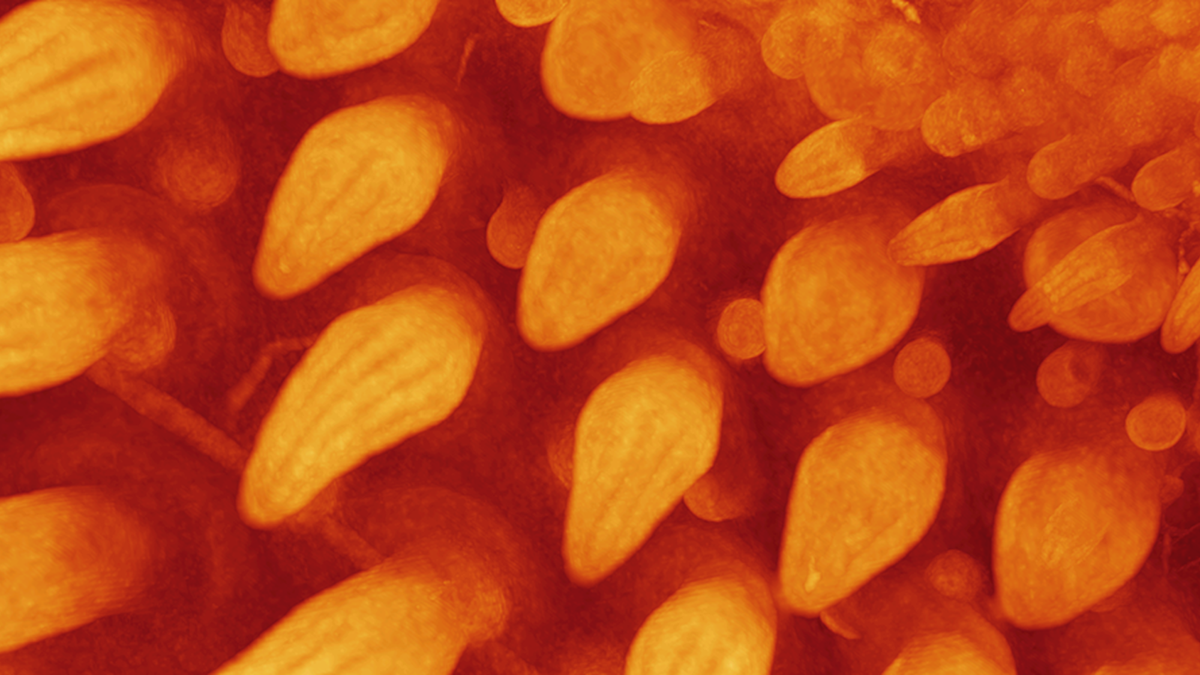

The first feathers were not the complicated, branching features seen on birds today. They were single tubules, shaped like tiny drinking straws. To find out how evolution built everything from soft down to gaudy peacock feathers from these simple tubes, Milinkovitch and Cooper first used a technique called light sheet fluorescence microscopy to examine chicken feather development in the egg. This method uses lasers to image thin slices of a sample.

Feathers start to develop in embryonic chickens nine days after the egg is laid. First, thick spots called placodes pop up all over the developing chicken, the researchers observed. Next, these placodes grow feather buds, which gradually develop into the familiar branching feather form with the help of keratin, the same protein found in human hair and fingernails. The Sonic Hedgehog gene, which is well known to guide embryonic development in animal species, plays a role in all of these steps.

Next, the researchers injected an inhibitor of the Sonic Hedgehog gene into eggs on the ninth day of development to see what would happen. Within days, feather bud growth was stunted. The inhibitor also reduced the complex branching pattern that develops as feathers mature on the embryo.

By day 17 of development, however, the feather growth had partially recovered as the inhibition of the Sonic Hedgehog gene wore off. Chickens that were allowed to hatch had patchy feathers, with some naked spots and other places where soft, down-like feathers had formed, but they did not have outer feathers with a central “rachis,” the distinctive quill structure in feathers. By the 49th day of life, however, these chickens molted, and the new feathers that came in developed normally.

The studies show that the Sonic Hedgehog gene has been involved both in the evolution of proto-feathers into today’s feathers, as well as in the diversification of feathers into different shapes and sizes across species, the researchers reported March 19 in the journal PLOS Biology.

“The big challenge now,” Milinkovitch said, “is to understand how these genetic interactions have changed to allow for the emergence of protofeathers early in the evolution of dinosaurs.”