Scientists have taken an important step toward understanding why human eggs grow more prone to chromosomal errors as they age and whether that decline could be circumvented someday.

The research, published in November in the journal Nature Aging, introduces a new tool that enables scientists to replicate changes seen in eggs during the aging process. The technique, which uses mouse egg cells, doesn’t require researchers to wait for the mice to age or to collect aged human eggs for study, and it enables them to zero in on different forces that might contribute to an egg’s decline.

This research is in its early days, but eventually, the study authors hope it could help extend the reproductive windows of women who plan to have children later in life.

“Female reproductive aging is a major source of inequity,” said senior study author Binyam Mogessie, an assistant professor at the Yale University School of Medicine. “Women have to make choices men don’t have to make” when it comes to weighing when to start a family. Notably, the rate of under-30 births is now trending down as over-30 births trend up in the U.S. In short, more women are having babies at older ages, when the rate of chromosomal abnormalities begins to rise.

“Even if we can extend this reproductive window by three years, it would be so consequential to the lives of so many people,” Mogessie told Live Science.

A model of aging eggs

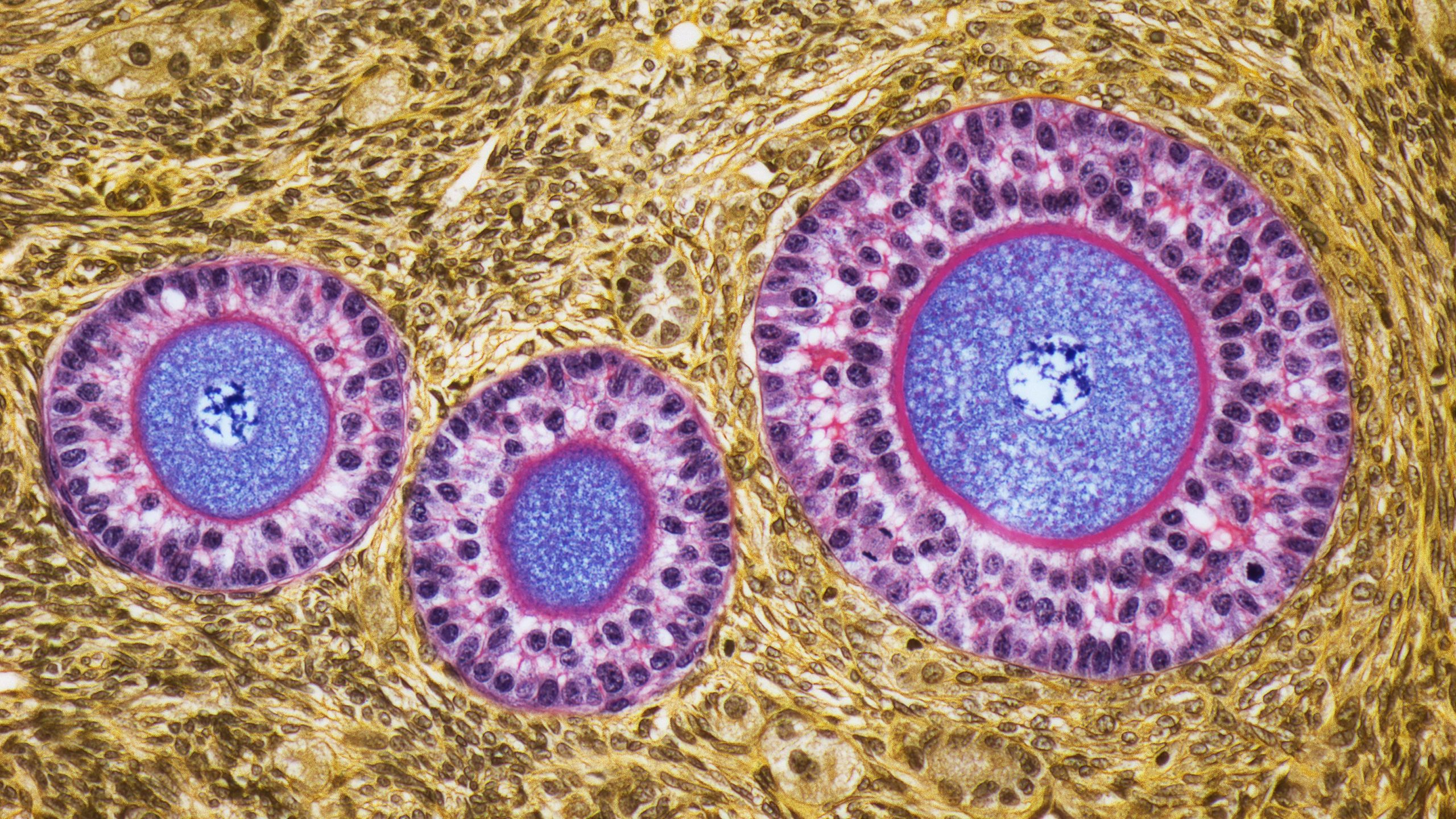

Women are born with all the egg cells they’ll ever carry, and over time, those eggs are released via the menstrual cycle. Eggs that have yet to be released hang out in the ovaries, where many will stay for decades.

Around age 30, this waiting egg supply shows a sharp uptick in aneuploidy risk, meaning the eggs are more likely to carry an abnormal number of chromosomes — either more or less than 46. Studies show that the risk of egg aneuploidy grows almost exponentially after age 35, and then jumps again at 40 and at 45. These chromosomal abnormalities can contribute to infertility and pregnancy loss in women, as well as genetic disorders in children, some of which can cause severe disability or death.

Scientists are still unsure why aneuploidy risk goes up so much with age. “The leading theory is that the forces that hold these chromosomes together, before they are separated at fertilization, those forces are failing progressively with age,” Mogessie said.

At various points in an egg’s cell cycle, each of its chromosomes contains two “sister chromatids” held together by molecular glue, and those sisters later get pulled apart. That glue is known to weaken with age and thus lead to chromatid separation issues that contribute to aneuploidy. But that doesn’t tell the whole story; it doesn’t explain why we see a sharp rise in chromosomal errors starting around age 30, Mogessie said.

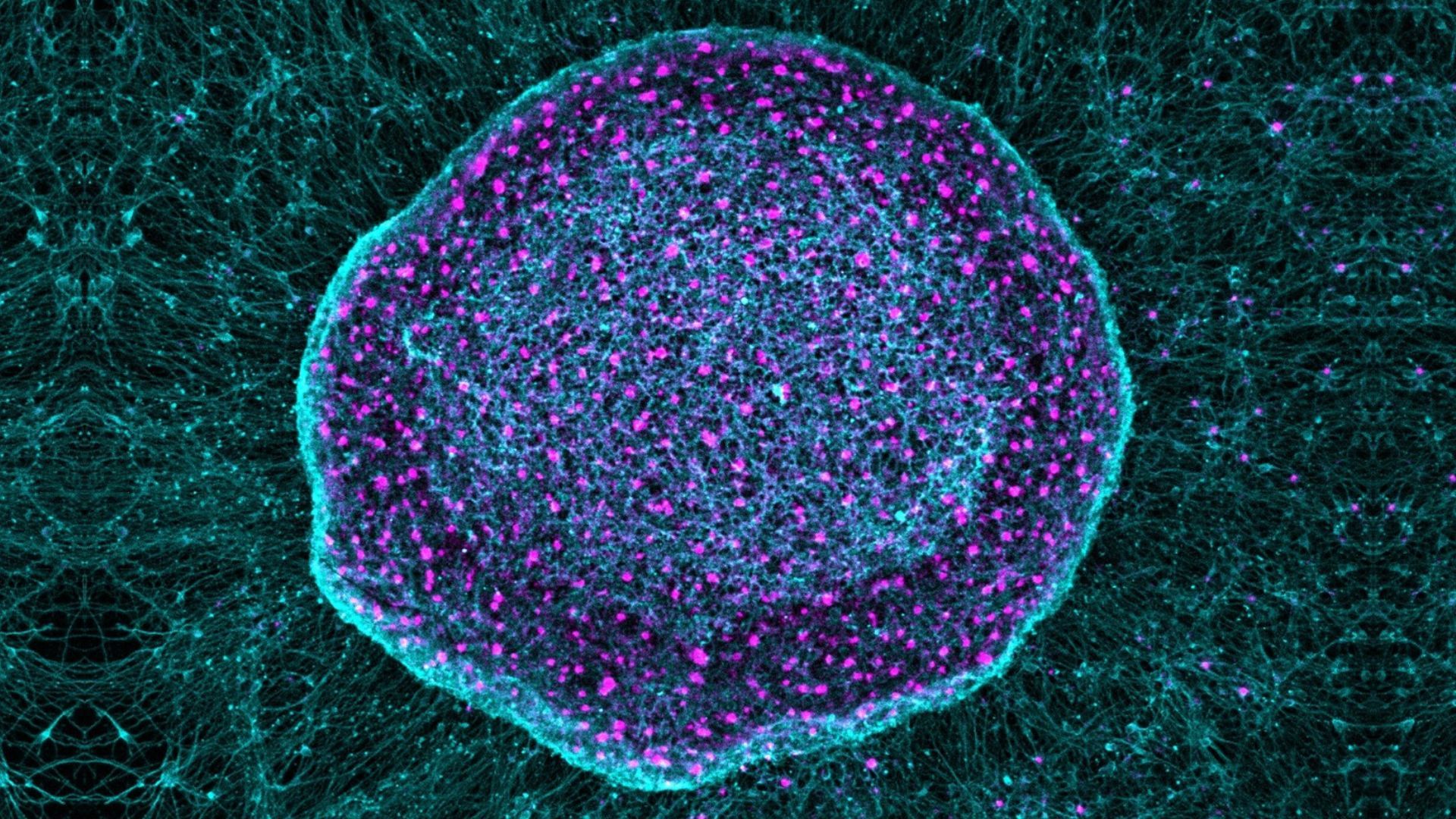

To investigate this mystery, the researchers developed an experimental setup to trigger “aging-like” changes in eggs and watch how the eggs changed afterward, using high-resolution time-lapse microscopy. A key part of the model was the use of the gene-editing system CRISPR to tweak a critical component of the molecular glue that holds chromosomes together: a protein called REC8.

This tweak added a switch to REC8, and once that switch was toggled “on,” the protein would degrade. Using this system, the scientists could tightly control the degree of REC8 breakdown in an egg, simulating what would happen naturally during aging.

“In animals, it can take years; in humans, it can take decades for these processes to arise,” Mogessie said. But the new technique “allows us to do this within 60 to 90 minutes.”

Previously, Mogessie and collaborators had used antibodies to mess with REC8 in a similar way, but this involved injecting the antibodies into delicate egg cells — a finicky and labor-intensive process — and the degree of degradation was difficult to control, Mihalas noted. Some benefits of the new system are that you avoid injecting the eggs and can tune REC8 levels much more precisely. “It is quite elegant,” she said.

Paving the way to future treatments

The team demonstrated that degrading REC8 to varying degrees led to errors in chromosome splitting and to aneuploidy, as you’d expect to see in naturally aged eggs. This also enabled them to pinpoint a specific threshold of REC8 loss at which the rate of errors suddenly spiked.

While the loss of REC8 could trigger these issues, scientists know that eggs decline in additional ways with age. To model this, the team messed with other proteins involved in holding chromosomes together, as well as with filaments that pull them apart when the time is right. These perturbations boosted the rate of chromosomal errors beyond what was seen with REC8 loss alone.

Taken together, these results suggest that the breakdown of chromosomes’ molecular glue likely sets the stage for aneuploidy. But the sudden spike seen in people in their 30s and 40s likely stems from the “synergistic failure” of multiple parts of this chromosome-separating machinery, the team said.

More research is needed to fully understand the impact of aging on eggs, but the new model should enable such work to be done. “The mouse model provides consistency,” Mihalas noted. Given the ethical challenges and limitations of working with human eggs, “it’s the best model we have,” Mihalas added.

In the long run, the model could be used to screen for and test the effects of potential treatments. There may be a way to turn back the clock and help eggs to reliably divide with fewer chromosomal errors, as they would have at younger ages.

“It really does set the scene for preventive measures aimed at improving the quality of eggs, at least in an IVF [in vitro fertilization] clinic setting,” Mogessie said. “I think that would have a huge impact.”

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.