Fossil collectors have discovered a prehistoric graveyard buried in Florida’s Steinhatchee River.

The site has yielded a remarkable collection of more than 500 fossils dating back roughly half a million years. It was full of exceptionally well-preserved bones from ancient mammals, including horses, giant armadillos, sloths and possibly a new species of tapir.

Around 500,000 years ago, before the river flowed over the site, a sinkhole opened up in Florida’s Big Bend region and became a death trap for hundreds of animals. Sediment filled the sinkhole over time, entombing their remains in near-pristine condition.

These fossils remained hidden until 2022, when fossil collectors Robert Sinibaldi and Joseph Branin stumbled upon them during a routine diving expedition in the river’s murky waters. After Branin spotted horse teeth sticking out of the sediment, the pair uncovered a hoof core and a tapir skull, signaling a potential major discovery.

“It wasn’t just quantity, it was quality,” Sinibaldi said in a statement released on Feb. 12 by the Florida Museum of Natural History. “We knew we had an important site, but we didn’t know how important.”

The Florida Museum recognized the significance of the find and dated it to the middle of the Irvingtonian North American Land Mammal Age (1.6 million–250,000 years ago)—an evolutionary transition period with a sparse fossil record.

“The fossil record everywhere, not just in Florida, is lacking the interval that the site is from,” Rachel Narducci, vertebrate paleontology collections manager at the Florida Museum and coauthor of a study of the site published Nov. 15 in the journal Fossil Studies, said in the statement.

Snapshots of evolutionary transitions

One of the key discoveries are fossils from an extinct giant armadillo-like creature called Holmesina. Within this genus, scientists knew that there was a transition from a species that lived two million years ago, the 150-pound H floridanus, to H. septentrionalis, which reached a whopping 475 pounds — but there was little evidence of how the change in size occurred.

“It’s essentially the same animal, but through time it got so much bigger and the bones changed enough that researchers published it as a different species,” Narducci said.

The fossils from the Steinhatchee River offer a snapshot of this evolutionary change, as the study revealed ankle and foot bones that match the size of the later, larger Holmesina species while retaining features of their smaller ancestors.

“This gave us more clues into the fact that the anatomy kind of trailed behind the size increase,” Narducci said. “So they got bigger before the shape of their bones changed.”

A glimpse at a new species?

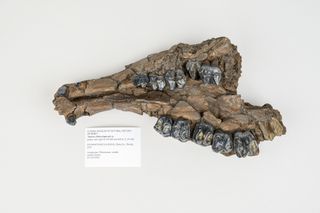

One intriguing specimen found at the site was the skull of an ancient tapir — a pig-shaped mammal with a short elephant-like trunk. Puzzlingly, the skull had lots of features not seen in the fossil record before, leading the researchers to consider whether the specimen might belong to a previously unknown species.

However, Richard Hulbert, lead author of the study, cautioned against making that leap just yet. “We need more of the skeleton to firmly figure out what’s going on with this tapir,” he said in the statement. “It might be a new species. Or it always could just be that you picked up the oddball individual of the population.”

Views of an ancient landscape

Among the 552 fossils recovered, about 75 percent belong to an early species of caballine horses — the subgroup that includes modern domestic horses.

Horses tend to dwell on large expanses of grassland rather than dense forests such as those that occupy the Big Bend region today. Since horses make up such a large chunk of the fossils discovered at Steinhatchee River, the researchers concluded that the site area may have once been more open and grassy.

Horse teeth were some of the best preserved fossils in the sinkhole. “For the first time, we had individuals that were complete enough to show us upper teeth, lower teeth and the front incisors of the same individual,” Richard Hulbert, lead author of the paper, said in the statement. With wear and tear still visible on the teeth, researchers may be able to study the horses’ diet in unprecedented detail.