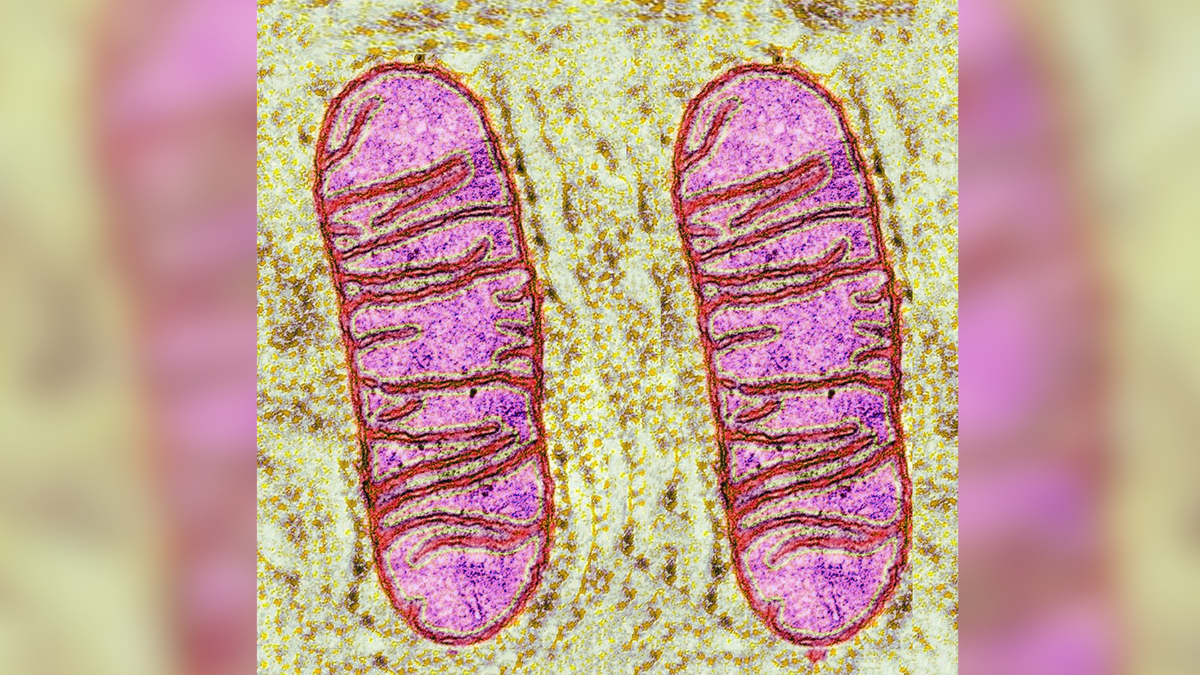

There are markers that sit on top of DNA and change over the course of one’s lifetime, and they can even be passed down to future generations. These “epigenetic” markers alter how genes are expressed — without changing their codes — and they can change based on a person’s experiences and environment.

Research suggests that stressful events can tweak a person’s epigenetics — but what happens on a larger scale? How do people’s epigenetics change, for example, in a population exposed to upheaval or violence multiple times over generations?

A new study, published Feb. 27 in the journal Scientific Reports, sought to answer that question.

An international collaboration of researchers convened by Rana Dajani, a molecular biologist at Hashemite University in Jordan, published first-of-their-kind results: they found that epigenetic signatures of trauma can be passed down through generations of people. The study was conducted with three generations of Syrian families that experienced the Hama massacre in 1982 and the Syrian uprising that began in 2011.

Related: Sperm cells carry traces of childhood stress, epigenetic study finds

“This is an interesting and fascinating study that emphasizes the importance of considering how traumatic experience can have an impact across multiple generations,” Michael Pluess, a developmental psychology researcher at the University of Surrey in the U.K. who was not involved in the work, told Live Science in an email.

A multinational and multigenerational collaboration

Dajani mainly studies the genetics of ethnic populations in Jordan but always had an interest in stress and epigenetic inheritance. There were several studies in lab animals that suggested epigenetic changes can pass from one generation to the next.

However, the question of whether epigenetic signatures of trauma and displacement can pass between generations of people had yet to be answered.

As a daughter of a Syrian refugee, Dajani realized she was in a unique position to probe the question.

“It clicked in my mind, ‘Wait a minute; we can actually answer this question because of the unique characteristics and the unique history that the Syrian community has gone through,'” Dajani told Live Science.

Dajani brought the idea to Catherine Panter-Brick, an anthropologist at Yale University with expertise on stress biomarkers and global health, and Connie Mulligan, an epigeneticist at the University of Florida who focuses on childhood adversity. The three scientists spent the next decade partnering on the study.

Dajani and Dima Hamadmad, a co-author of the study and a daughter of Syrian refugees, contacted families all over the world mainly through word of mouth. The researchers sat down with the families and listened to their stories; they also explained the science of epigenetics, what they could expect from the study’s results, and how these results could bring awareness to their stories.

“They [the families] felt gratified because, first, they understood the science, and second, they felt agency — that they were doing something in response to what happened to them,” Dajani said.

“This could have only happened because … I’m a scientist and I’m Syrian. So it’s somebody from the community center.”

The Hama massacre was an assault by the government on the west-central city of Hama, during which an estimated 10,000 to 40,000 people were either killed or disappeared. The Syrian uprising that began in 2011 resulted in the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians protesting the Assad government regime.

It took seven years to find families with three generations of women willing to participate in the study and gather enough samples to meet its criteria. The researchers collected blood samples from grandmothers who had been pregnant during the 1982 attack, as well as from their daughters and granddaughters.

They also collected samples from mothers who had been pregnant during the 2011 uprising and from their mothers and daughters.

Additionally, the research team found families with daughters where one was a child during the 2011 uprising, and thus had direct exposure to trauma, while the other daughter was still in the womb at the time.

Finally, they took samples from Syrian families that had left the country before either incident, to use as a point of comparison.

“You cannot find three generations of humans who have been subjected to the brutality of war in such a discrete way with grandmothers versus mothers versus children being exposed or non-exposed to war. So that’s a very unique design,” Panter-Brick said.

Related: Scientists just rewrote our understanding of epigenetics

Epigenetic marks of trauma

An analysis of the samples revealed 21 distinct epigenetic changes in the genome that were unique to those who had direct exposure to trauma. An additional 14 changes seemed to be unique to the grandchildren of grandmothers who were exposed to trauma while pregnant.

Together, these changes occurred at 35 sites along the genome. And the data hinted that, at the majority of those sites, the same pattern of epigenetic changes unfolded regardless of the type of exposure — direct, prenatal or from a prior generation.

Specifically, one common type of epigenetic change is the addition or subtraction of a compound — called a methyl group — from DNA. So across the different trauma types, most of the sites showed methylation in the “same direction,” either adding or subtracting.

However, that finding wasn’t statistically significant, likely due to the relatively small sample sizes in each group, the authors noted. So the findings bear confirming in larger samples.

“What it seems to say is that there might be a common epigenetic signature of violence across generations, exposures and developmental stages,” Mulligan told Live Science.

The analysis also found that children who were exposed to trauma in the womb appeared epigenetically “older” than their chronological ages; this was not seen in other modes of exposure. So-called accelerated epigenetic aging has been linked to a number of health issues, but it’s unclear whether the epigenetic changes drive the health problems or simply reflect them.

Mulligan suggested that this aging effect could be the result of trauma exposure during a highly active stage of fetal development, which could explain why it was only seen in the context of prenatal exposure.

What does this mean for human health?

The scientists don’t yet know what differences these epigenetic signatures might mean for human health.

Mulligan suggested that the marks “might have allowed humans to adapt to environmental stressors, particularly psychosocial stress and violence.” The theory would need to be confirmed in future research.

Looking ahead, the researchers plan to continue investigating what these epigenetic changes mean biologically, as well as study other groups of people and see if the same sites are changed.

Dajani previously published work about how studies like these can shift our perspective on traumatic events.

“We can use this framing to go from victimhood and vulnerability to agency and adaptability,” she said. “We can propose that our discovery is proof that humans inherit this adaptability so that they can cope with future unpredictable environments.”

Dajani also recently became a grandmother and reflected on what she would say to her granddaughter about the discovery.

“Even though your grandparents or great-grandparents went through something, you have the tenacity, the ‘sumud’ [an Arabic word meaning “steadfastness”], to go forward and thrive and flourish,” she said.

For Panter-Brick, “it’s just pure joy to see the actual results come to fruition at this point.

“And it just means a lot for the population themselves, for our team of women scientists, and for the results of science,” she added. “But this is [also] an example of how we can work together for the benefit of humanity by understanding more about the challenges that humans repeatedly find themselves in when they face different kinds of violence.”