South Korea’s month-long political crisis saw another day of high drama with police failing to arrest suspended President Yoon Suk Yeol after a six-hour standoff.

Authorities had sought to arrest Yoon over his short-lived martial law declaration in early December – but they spent half the day locked in confrontation with the presidential security team.

This follows an unprecedented few weeks in which the opposition-dominated parliament voted to impeach Yoon and then the man who succeeded him as acting president.

Although hundreds of Yoon supporters gathered outside the presidential residence to protest the arrest, his future remains uncertain.

Officers were seeking to arrest him as part of a criminal investigation into the martial law declaration. But his fate is also in the hands of the country’s constitutional court, which can remove him from office by upholding the impeachment vote.

Why did Yoon impose martial law?

It was an hour to midnight on 3 December when South Korea’s President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law – which had never happened since the country became a democracy in 1987.

Yoon said he was protecting the country from “anti-state” forces that sympathised with North Korea – but it soon became clear that he was spurred by his own political troubles.

Ever since he took office in May 2022, Yoon has weathered scandals and low ratings. In 2024, he became a lame-duck president after the main opposition Democratic Party won by a landslide general elections. He was reduced to vetoing bills passed by the opposition, a tactic that they used with “unprecedented frequency”, says Celeste Arrington, director of The George Washington University Institute for Korean Studies.

Days before 3 Dec, the opposition slashed the budget Yoon’s government had proposed. And the opposition was also moving to impeach cabinet members for failing to investigate first lady Kim Keon Hee, who has also been embroiled in scandal.

Up against these political challenges, and reportedly under the advice of senior aides, Yoon decided to impose martial law.

But the decison sparked protests and public anger.

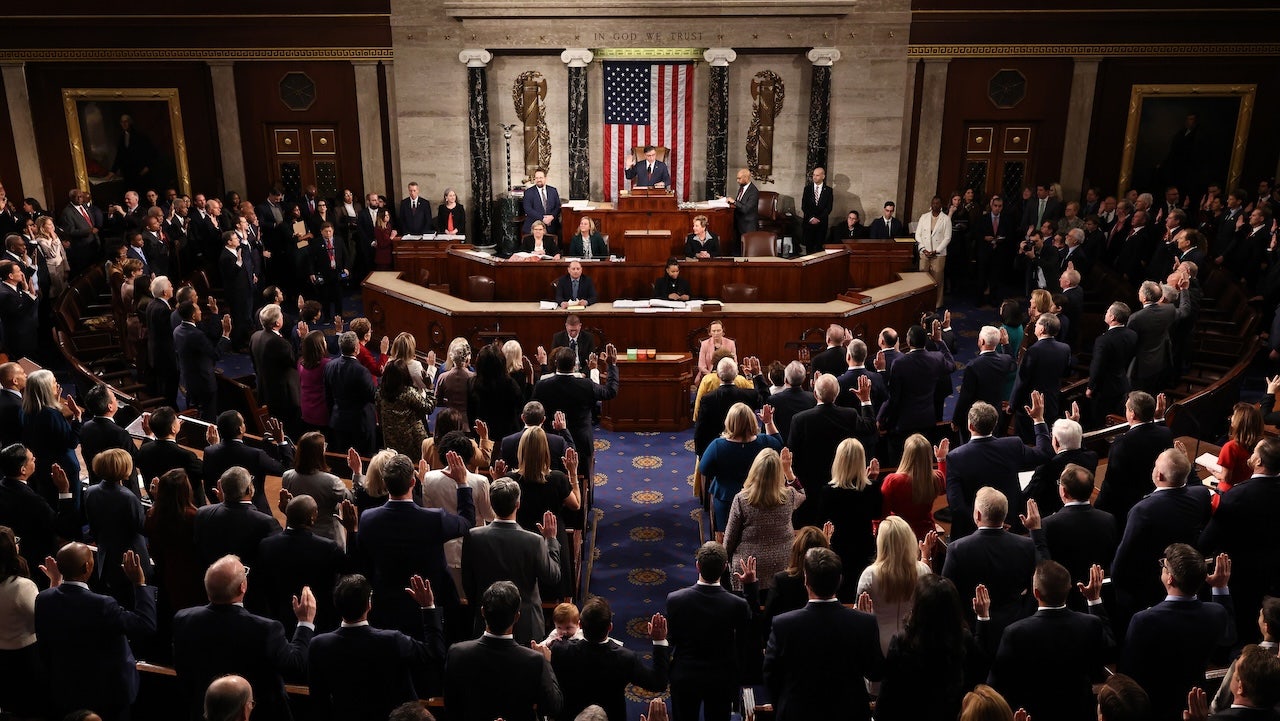

MPs voted down the declaration, with many climbing fences and breaking barricades to enter the heavily guarded National Assembly to do so.

Lawmakers across the political spectrum decried the move as unconstitutional. Even the then-leader of Yoon’s conservative People’s Power Party called it “wrong”.

Days and nights of protests followed in the chilly temperatures, with tens of thousands of people calling for Yoon to be removed from office.

“No martial law!” they chanted. “Strike down dictatorship!”

What happened next?

Opposition lawmakers soon filed a motion to impeach Yoon – it needed a two-thirds majority to pass.

With 192 of 300 seats in hand, the oppoition Democratic Party still required eight PPP members to vote for impeachment. But Yoon’s party members toed the line in that first vote, boycotting it to walk out of the chamber en masse.

An undeterred opposition vowed to file an impeachment motion every week until passed. But their second attempt on 14 Dec was successful, with 12 members of Yoon’s party voting for impeachment, alongside the opposition.

Yoon was suspended from office and is now awaiting the decision of the constitutional court, which has to decide within six months of the impeachment vote. Analysts expect judges to reach a verdict by February.

If Yoon is removed, the country must hold an election within the next 60 days to vote for a new leader. DP’s leader Lee Jae-myung is the frontrunner by large margin in opinion polls.

Meanwhile, the politcial uncertainty continues.

Yoon’s successor, Prime Minister Han Duck-soo who had stepped in as acting president, has also been impeached – the opposition accused him of stalling Yoon’s impeachment process. Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok is now acting president and acting prime minister.

Several former cabinet ministers and Yoon’s presidential aides have resigned over the events on 3 Dec. Some of them have been detained by the Corruption Investigation Office (CIO), which is investigating Yoon for abusing his power and inciting an insurrection with the martial law order.

Among those detained is former defence minister Kim Yong-hyun, who reportedly suggested the martial law declaration to Yoon. Kim had tried to take his own life while in detention.

The failed attempt to arrest Yoon

Yoon has remained defiant throughout, refusing multiple summonses to appear for questioning, leading a Seoul court to issue a warrant for his arrest.

On 3 January, about 100 police and CIO officers went up against the president’s security team at his home in central Seoul.

Finally the CIO suspended its operation after a six-hour standoff, citing safety concerns for its team on the ground.

Investigators have until 6 January to arrest him before the warrant expires – after that they would need to apply for another warrant to detain him.

The acting president has pledged to do all he can to restore stability, but if the opposition finds him uncooperative, they could move to impeach him.

It’s been an unprecedented month in South Korea. Yoon is the first sitting president to face arrest and what comes next remains unclear.

Financial markets have reacted badly to the uncertainty – at the end of December, the South Korean won plunged to its lowest level against the dollar since the global financial crisis in 2008.

South Korea is one of the world’s most important economies and a crucial US ally – so turmoil on its shores is unwelcome on many fronts.

Additional reporting by Frances Mao in London