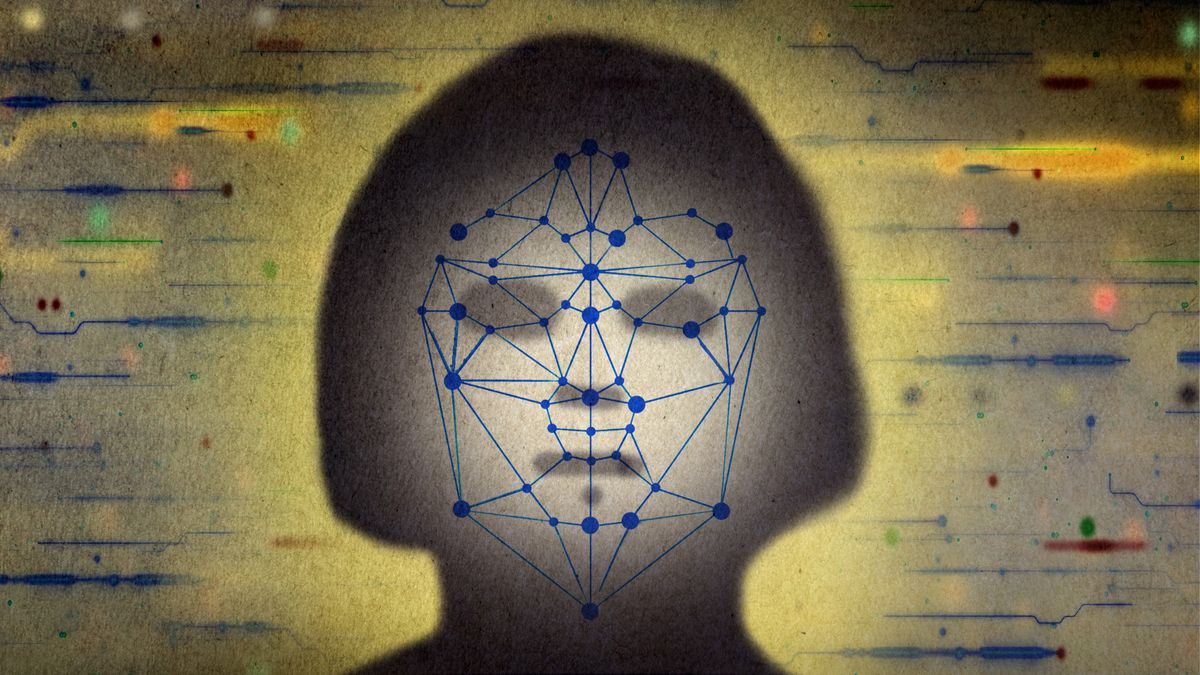

In this extract from “Your Face Belongs to Us” (Simon & Schuster, 2023), journalist Kashmir Hill recalls the emergence of Clearview AI, the facial recognition technology company that burst into public consciousness with its artificial intelligence (AI) software that could supposedly identify pretty much anyone with just a single shot of their face.

In November 2019, I had just become a reporter at The New York Times when I got a tip that seemed too outrageous to be true: A mysterious company called Clearview AI claimed it could identify just about anyone based only on a snapshot of their face.

I was in a hotel room in Switzerland when I got the email, on the last international plane trip I would take for a while because I was six months pregnant. It was the end of a long day and I was tired but the email gave me a jolt. My source had unearthed a legal memo marked “Privileged & Confidential” in which a lawyer for Clearview had said that the company had scraped billions of photos from the public web, including social media sites such as Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn, to create a revolutionary app.

Give Clearview a photo of a random person on the street, and it would spit back all the places on the internet where it had spotted their face, potentially revealing not just their name but other personal details about their life. The company was selling this superpower to police departments around the country but trying to keep its existence a secret.

Not so long ago, automated facial recognition was a dystopian technology that most people associated only with science fiction novels or movies such as “Minority Report.” Engineers first sought to make it a reality in the 1960s, attempting to program an early computer to match someone’s portrait to a larger database of people’s faces. In the early 2000s, police began experimenting with it to search mug shot databases for the faces of unknown criminal suspects. But the technology had largely proved disappointing. Its performance varied across race, gender, and age, and even state-of-the-art algorithms struggled to do something as simple as matching a mug shot to a grainy ATM surveillance still.

Clearview claimed to be different, touting a “98.6% accuracy rate” and an enormous collection of photos unlike anything the police had used before.

This is huge if true, I thought, as I read and reread the Clearview memo that had never been meant to be public. I had been covering privacy, and its steady erosion, for more than a decade. I often describe my beat as “the looming tech dystopia — and how we can try to avoid it,” but I’d never seen such an audacious attack on anonymity before.

Privacy, a word that is notoriously hard to define, was most famously described in a Harvard Law Review article in 1890 as “the right to be let alone.” The two lawyers who authored the article, Samuel D. Warren, Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis, called for the right to privacy to be protected by law, along with those other rights — to life, liberty, and private property — that had already been enshrined. They were inspired by a then-novel technology — the portable Eastman Kodak film camera, invented in 1888, which made it possible to take a camera outside a studio for “instant” photos of daily life — as well as by people like me, a meddlesome member of the press.

“Instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise have invaded the sacred precincts of private and domestic life,” wrote Warren and Brandeis, “and numerous mechanical devices threaten to make good the prediction that ‘what is whispered in the closet shall be proclaimed from the house-tops.'”

Related: Humanity faces a ‘catastrophic’ future if we don’t regulate AI, ‘Godfather of AI’ Yoshua Bengio says

This article is among the most famous legal essays ever written, and Louis Brandeis went on to join the Supreme Court. Yet privacy never got the kind of protection Warren and Brandeis said that it deserved. More than a century later, there is still no overarching law guaranteeing Americans control over what photos are taken of them, what is written about them, or what is done with their personal data. Meanwhile, companies based in the United States — and other countries with weak privacy laws — are creating ever more powerful and invasive technologies.

Facial recognition had been on my radar for a while. Throughout my career, at places such as Forbes and Gizmodo, I had covered major new offerings from billion-dollar companies: Facebook automatically tagging your friends in photos; Apple and Google letting people look at their phones to unlock them; digital billboards from Microsoft and Intel with cameras that detected age and gender to show passers-by appropriate ads.

I had written about the way this sometimes clunky and error-prone technology excited law enforcement and industry but terrified privacy-conscious citizens. As I digested what Clearview claimed it could do, I thought back to a federal workshop I’d attended years earlier in Washington, D.C., where industry representatives, government officials, and privacy advocates had sat down to hammer out the rules of the road.

The one thing they all agreed on was that no one should roll out an application to identify strangers. It was too dangerous, they said. A weirdo at a bar could snap your photo and within seconds know who your friends were and where you lived. It could be used to identify anti-government protesters or women who walked into Planned Parenthood clinics. It would be a weapon for harassment and intimidation. Accurate facial recognition, on the scale of hundreds of millions or billions of people, was the third rail of the technology. And now Clearview, an unknown player in the field, claimed to have built it.

I was skeptical. Startups are notorious for making grandiose claims that turn out to be snake oil. Even Steve Jobs famously faked the capabilities of the original iPhone when he first revealed it onstage in 2007.*

We tend to believe that computers have almost magical powers, that they can figure out the solution to any problem and, with enough data, eventually solve it better than humans can. So investors, customers, and the public can be tricked by outrageous claims and some digital sleight of hand by companies that aspire to do something great but aren’t quite there yet.

But in this confidential legal memo, Clearview’s high-profile lawyer, Paul Clement, who had been the solicitor general of the United States under President George W. Bush, claimed to have tried out the product with attorneys at his firm and “found that it returns fast and accurate search results.”

Clement wrote that more than 200 law enforcement agencies were already using the tool and that he’d determined that they “do not violate the federal Constitution or relevant existing state biometric and privacy laws when using Clearview for its intended purpose.” Not only were hundreds of police departments using this tech in secret, but the company had hired a fancy lawyer to reassure officers that they weren’t committing a crime by doing so.

I returned to New York with an impending birth as a deadline. I had three months to get to the bottom of this story, and the deeper I dug, the stranger it got…

Concerns about facial recognition had been building for decades. And now the nebulous bogeyman had finally found its form: a small company with mysterious founders and an unfathomably large database. And none of the millions of people who made up that database had given their consent. Clearview AI represents our worst fears, but it also offers, at long last, the opportunity to confront them.

*Steve Jobs pulled a fast one, hiding the prototype iPhone’s memory problems and frequent crashes by having his engineers spend countless hours on finding a “golden path”—a specific sequence of tasks the phone could do without glitching.

Your Face Belongs to Us: The Secretive Startup Dismantling Your Privacy by Kashmir Hill has been shortlisted for the 2024 Royal Society Trivedi Science Book Prize, which celebrates the best popular science writing from across the globe.