Neanderthals were the world’s first innovators of fire technology, tiny specks of evidence in England suggest. Flecks of pyrite found at a more than 400,000-year-old archaeological site in Suffolk, in eastern England, push back archaeologists’ evidence for controlled fire-making and suggest that key human brain developments began far earlier than previously thought.

“We’re a species who’ve used fire to really shape the world around us,” study co-author Rob Davis, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the British Museum, said in a news conference on Tuesday (Dec. 9). “The ability to make fire would have been critically important” in human evolution, Davis said, “accelerating evolutionary trends” such as developing larger brains, maintaining larger social groups, and increasing language skills.

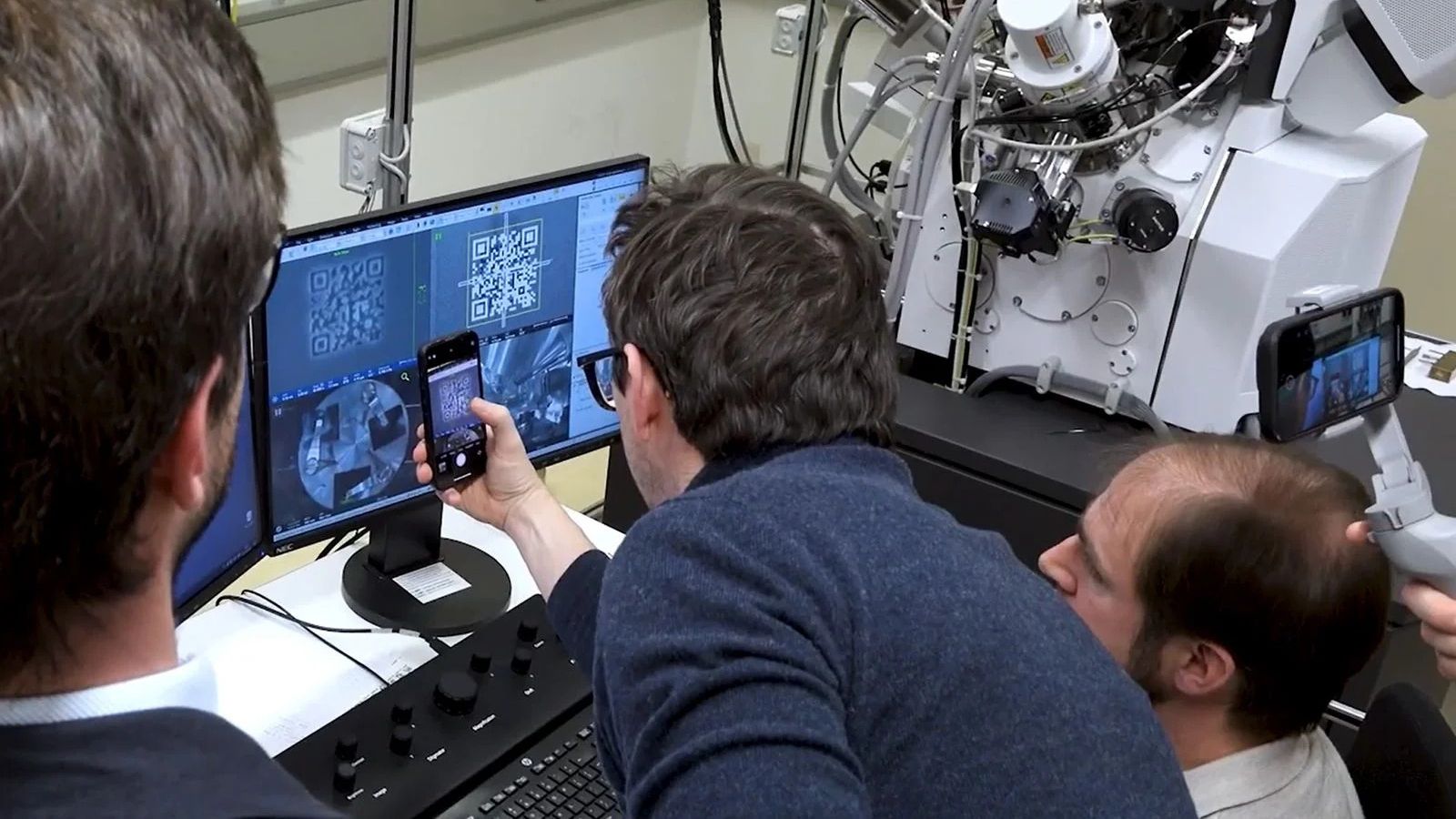

Since 2013, Davis and colleagues have been excavating an archaeological site in England called Barnham, which yielded stone tools, burnt sediment and charcoal from 400,000 years ago. In a study published Wednesday (Dec. 10) in the journal Nature, the researchers revealed that the site contained the world’s earliest direct evidence of fire-making — and that this fire technology was likely pioneered by Neanderthals.

A big turning point

Barnham was first recognized as a Paleolithic human site in the early 1900s due to the presence of stone tools. But recent excavations uncovered evidence of ancient human groups occupying the area more than 415,000 years ago, when Barnham was a small, seasonal watering hole in a woodland depression.

In one corner of the site, archaeologists found a concentration of heat-shattered hand axes as well as a zone of reddened clay. Through a series of scientific analyses, the researchers discovered that the reddened clay had been subjected to repeated, localized burning, which suggested the area may have been an ancient hearth.

“The big turning point came with the discovery of iron pyrite,” study co-author Nick Ashton, curator of Paleolithic collections at the British Museum, said in the news conference.

Pyrite, also known as fool’s gold, is a naturally occurring mineral that can produce sparks when struck against flint. While pyrite is found in many locations around the world, it is extremely rare in the Barnham area, meaning someone specifically brought pyrite to the site, probably with the aim of making fire, the researchers said in the study.

Humans’ use of fire

Because of the importance of controlled fire, paleoanthropologists have long debated the timing of this invention.

“There are so many obvious advantages to fire, from cooking to protection from predators to its technological use in creating new types of artifacts to its ability to bring people together,” April Nowell, a Paleolithic archaeologist at the University of Victoria in Canada who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email. “We only have to think of our own childhoods gathering around a campfire to understand its emotional resonance.”

Researchers believe that early humans first used wildfires for cooking food. This was a crucial step in human evolution because cooking widened the range of food available and made it more digestible, which in turn provided more nutrients needed to grow a larger brain, Davis said.

But there is limited evidence for deliberate early fire technology, and that evidence is often ambiguous, the researchers noted in the study.

For example, scientists unearthed reddened sediment at Koobi Fora in Kenya that dated to about 1.5 million years ago. Researchers suggested it could hint at early fire use because the key hominin at the site — Homo erectus — had a fairly large brain. And at two sites in Israel dated to about 800,000 years ago, burnt animal bones and stone tools suggest possible control of fire by the human ancestors who lived there.

Fire technology then exploded around 400,000 years ago. Archaeologists have found evidence of burning at cave sites in France, Portugal, Spain, Ukraine and the U.K., and then more widespread use of fire in Europe, Africa and the Levant (the region around the east Mediterranean) by 200,000 years ago.

But these previous examples do not show the same kind of conclusive geochemical evidence of fire making that was found at Barnham, Ashton argued. He called the team’s careful analysis of the Barnham sediment and identification of pyrite “the most exciting discovery in my 40-year career.”

Neanderthals are “fully human”

However, any bones at Barnham have since disintegrated, so the “smoking gun” of butchered and burned animal bones that could prove the site was used for cooking has not been found.

This also means there are no skeletal remains of the fire producers themselves at Barnham — but study co-author Chris Stringer, a paleoanthropologist at the National History Museum in London, has a guess about their identity.

“We assume that the fires at Barnham were being made by early Neanderthals,” Stringer said in the news conference, based on a nearby site called Swanscombe, where Neanderthal skull bones were discovered that dated to the same time period as Barnham.

While experts have known for about a decade that some Neanderthals could make fire, that evidence goes back only 50,000 years. The Barnham finds push that date 350,000 years further back, suggesting Neanderthals were much smarter than most people give them credit for.

Neanderthals “are fully human,” Stringer said. “They have complex behavior, they’re adapting to new environments, and their brains are as large as ours. They’re very evolved humans.”

Nowell said that the study’s results add fuel to a larger debate about Neanderthals’ control of fire and their social and cultural use of it.

“There is a lot of discussion right now about whether all Neanderthals made fire or if it is only some Neanderthals at some times and places that made fire,” Nowell said. The new study “is another important data point in our understanding of Neanderthal pyrotechnical capabilities with all that implies cognitively, socially and technologically.”

Who made fire first?

If the researchers are correct that Neanderthals made fire from flint and pyrite more than 400,000 years ago in England, this raises additional questions, Nowell said.

“Despite its obvious advantages, questions remain about the nature of early fire use: When did fire use become a regular part of the human behavioral repertoire? Were early humans dependent on the opportunistic use of wildfires and lightning strikes? Was fire rediscovered multiple times?” Nowell said.

The ancestors of Homo sapiens were living in Africa 400,000 years ago and not likely interacting with early Neanderthals half a world away.

“We don’t know if Homo sapiens at that date had the ability to make fire,” Stringer said, because to date there is no clear evidence for control of fire any earlier than Barnham.

This means that Neanderthals may have invented ways to make and control fire somewhere in continental Europe, which then enabled our human cousins to move further north into England, heating and lighting their way with fire.

“It’s plausible that fire became more controlled in Europe and spread to Africa,” Ashton said. “We have to keep an open mind.”