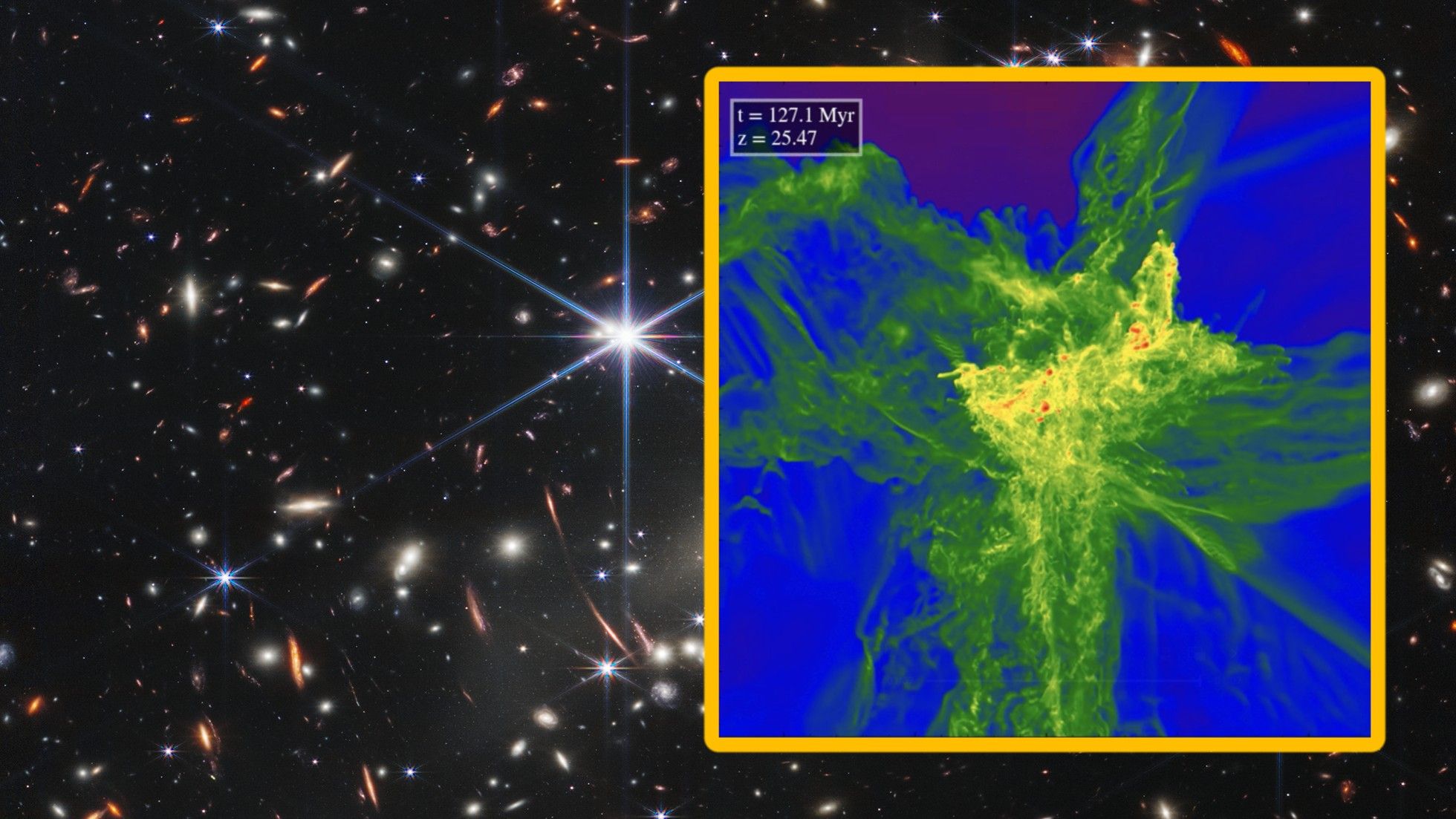

Scientists using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have spotted the first evidence of “monster stars” in the early universe — offering new clues to how supermassive black holes grew so big after only a billion years of the universe’s history.

The team spotted these gargantuan stars — each with a mass of between 1,000 and 10,000 times our sun — in a galaxy called GS 3073, which formed roughly about a billion years after the Big Bang. It is believed that monster stars like these led to the formation of these early supermassive black holes.

A peculiar signature

The stars in GS 3073 had an unusual and “extreme” imbalance of nitrogen to oxygen (a ratio of 0.46) not usually found in stars or stellar explosions, according to the team. The signature, however, matched something predicted in models: “primordial stars thousands of times more massive than our sun,” study co-author Devesh Nandal, a postdoctoral fellow at the CfA’s Institute for Theory and Computation, said.

How did these stars produce so much nitrogen? The researchers said it’s a three-step process. Stars are constantly burning elements in their cores. As these large stars in GS 3073 burned helium, the chemical reactions created carbon. Eventually, carbon began to invade an outside shell of material, where hydrogen was burning. In that outside shell, the carbon and hydrogen then mixed to create nitrogen.

As the nitrogen was produced, convection currents within the star began to distribute it throughout the star’s body. Over time, the nitrogen left the star and flowed into space. In the case of GS 3073, this process lasted millions of years.

“The study also found that this nitrogen signature only appears in a specific mass range,” the researchers noted. “Stars smaller than 1,000 solar masses, or larger than 10,000 solar masses, don’t produce the right chemical pattern for the signature, suggesting a ‘sweet spot’ for this type of enrichment.”

The big black hole mystery

Based on their models, the researchers further suggested that when these monster stars reach the end of their lives, they don’t explode into supernovas. What happens next is instead a big collapse, generating some of the universe’s earliest supermassive black holes.

Adding more fuel to this idea: GS 3073 does appear to have an actively feeding black hole at its center, “potentially the very remnant of one of these supermassive first stars,” the statement noted. “If confirmed, this would solve two mysteries at once: where the nitrogen came from and how the black hole formed.”

The origin of the universe’s first supermassive black holes remains one of the biggest mysteries in astrophysics. Some theories suggest they collapsed directly from ultra-dense clouds of gas shortly after the Big Bang and then formed galaxies around them; other theories point to more exotic explanations, such as dark matter interactions or the collapse of monster stars. Ultimately, more research is needed to solve this ancient puzzle.