A 2,200-year-old bone unearthed in Spain may be from one of Hannibal’s war elephants that was deployed during the Second Punic War, a new study reports.

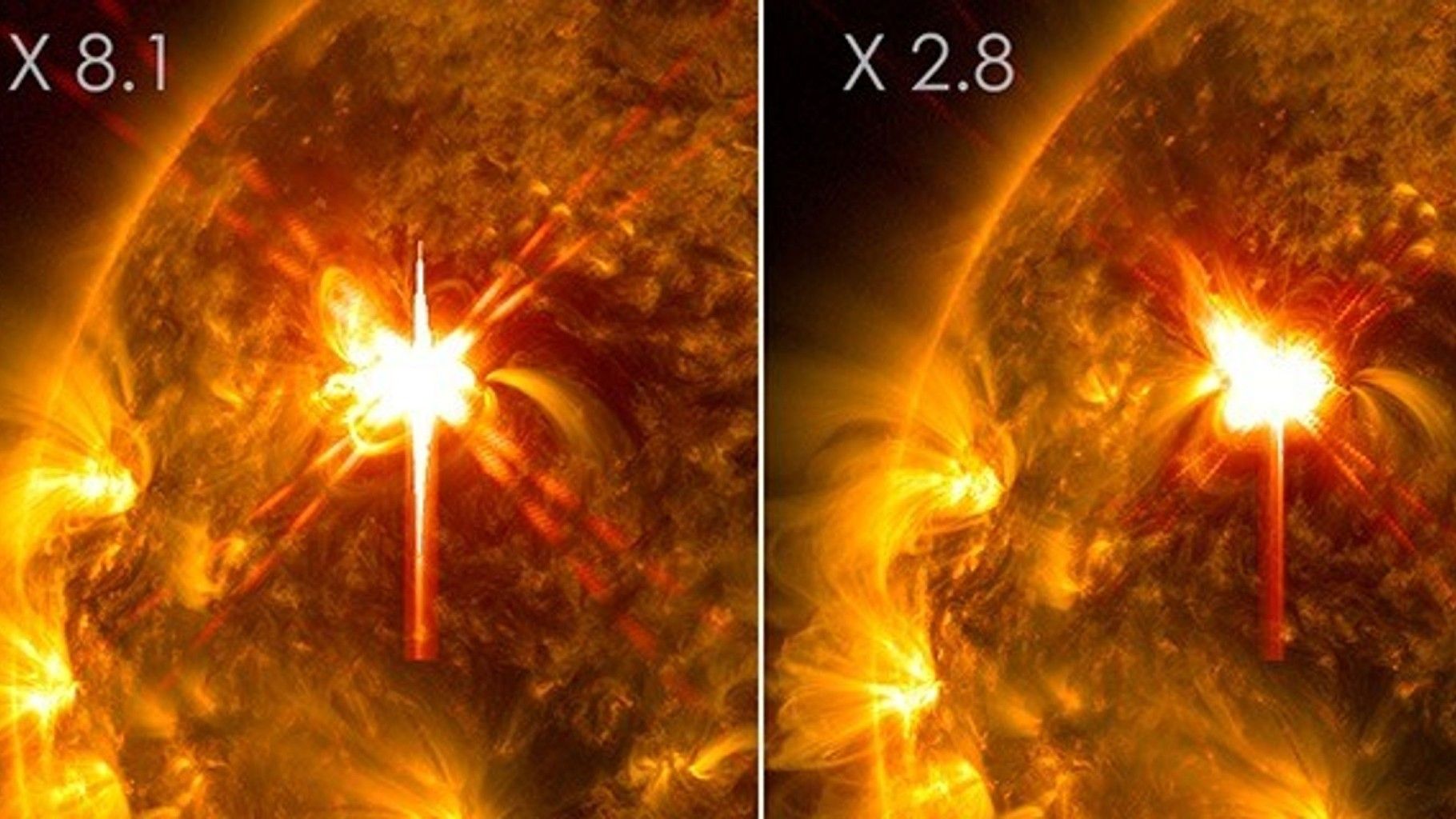

The baseball-size bone, found near the southern Spanish city of Córdoba, may be the only direct evidence of the Carthaginian general’s war elephants, according to the study, which was published in the February issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. Famously, 37 of these bellicose pachyderms trekked with Hannibal and his army for the length of Iberia, over the Pyrenees to southern Gaul, across the Alps and into Italy to attack Rome.

The bone “could prove to be a landmark,” Rafael Martínez Sánchez, an archaeologist at the University of Córdoba and the study’s first author, told Live Science. Until now, “there has been no direct archaeological testimony for the use of these animals,” he said in an email.

The mysterious bone was unearthed in 2019 and initially perplexed scientists because it matched no native animal. It was recognized years later as an elephant’s right carpal bone — the “ankle” of its right foreleg, which is equivalent to the wrist in humans. The researchers think this particular elephant was brought there as a beast of war by the Carthaginians.

Celtic stronghold

The bone was found during archaeological excavations at the site of a fortified Iberian village, in a layer of earth radiocarbon-dated to around 2,250 years ago — before the Romans took control of the region in about 150 B.C. The Romans called such fortified villages oppida; they were commonly used by the ancient Celts and were often built on hilltops, but this was in the defensible bend of a river.

Carthage, an ancient city state on the coast of what’s now Tunisia, originated as a Phoenician colony and its fleet of warships was especially feared. But its armies were also powerful, and Carthage used war elephants in the first two Punic Wars against the Roman Republic, which were largely for control of strategic regions of the western Mediterranean.

It seems a Carthaginian army stationed nearby during the Second Punic War (218 to 201 B.C.) had been involved in a battle at the ancient fortified village near Córdoba — and that the elephant was killed in the fighting, the researchers wrote in the study.

Other signs of a military conflict at the site included 12 spherical stones the researchers think were ammunition for Carthaginian catapults.

It seemed most of the elephant’s skeleton had rotted away, but the carpal bone had been protected by a collapsed wall, the researchers wrote. They do not rule out the possibility, however, that the bone had survived because it was taken as a souvenir, as it is small enough to carry.

Martínez Sánchez said it’s not currently possible to determine if the animal was an Asian elephant (Elephas maximus indicus) — the species the Greek king Pyrrhus of Epirus (known for his eponymous “Pyrrhic Victory”) had used against the Romans about 10 years before the First Punic War — or a now-extinct species of African elephant that the Carthaginians preferred for their war beasts.

Hannibal’s march

The Carthaginian general and nobleman Hannibal Barca started his famous attack on Rome in about 218 B.C., leading his armies into Italy the long way through Western Europe. Most of his war elephants died while crossing the Alps, but Hannibal’s armies were victorious against the Romans in Italy for many years.

Hannibal was recalled to Carthage in 203 B.C. to defend against Roman attacks there. But the Carthaginians ultimately lost their second war on Rome as they had the First Punic War more than 20 years earlier. (About 50 years later, Rome engineered a Third Punic War, which the weakened Carthaginians also lost and which led to their demise.)

The researchers stressed that the elephant that died near Córdoba could not have been one of the “legendary specimens” that crossed the Alps with Hannibal. However, the bone is a relic of the ancient Punic Wars for control of the Mediterranean and represents the “passage of the gigantic ‘tanks of antiquity’ through the [Iberian] peninsula,” the researchers wrote.