Scientists at Microsoft have built a new quantum computing chip using a special category of material capable of tapping into a new state of matter. This breakthrough could enable researchers to build a single chip with millions of reliable qubits much sooner than experts predicted — possibly within just a few years rather than decades.

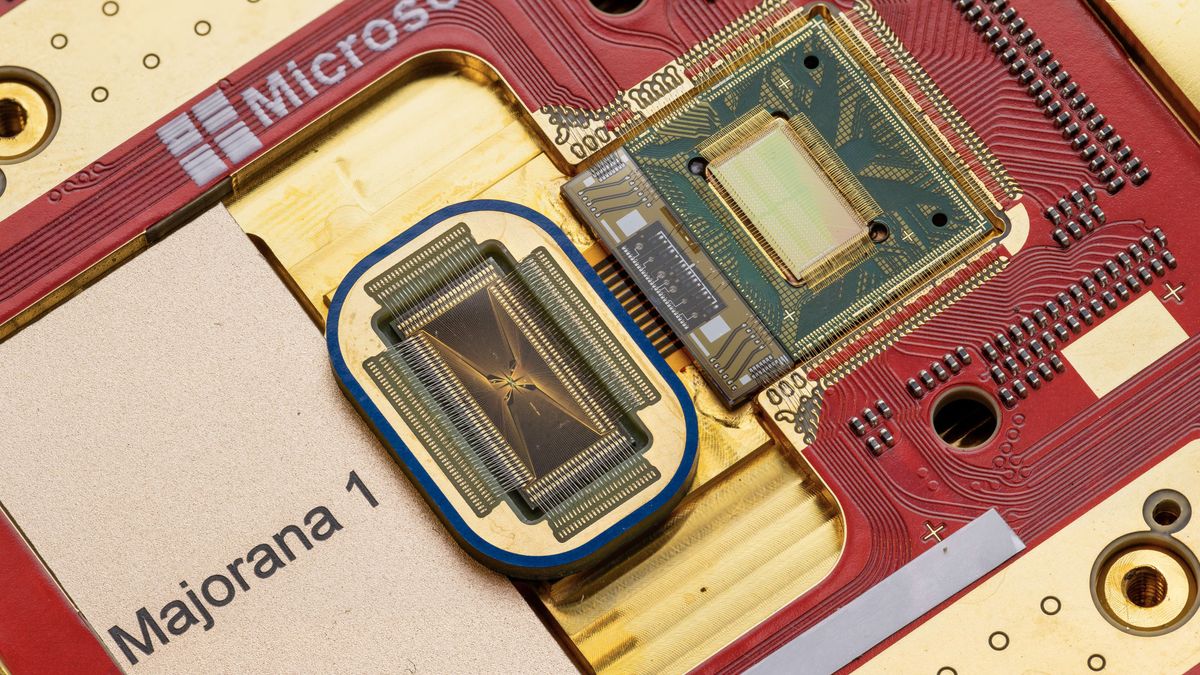

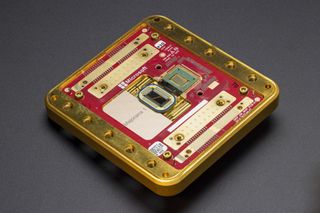

The new quantum processing unit (QPU), called “Majorana 1,” is an eight-qubit prototype chip built from the first material of its kind in the world — a topological conductor, or topoconductor. This can reach the “topological” state of matter and tap into the laws quantum mechanics under the right conditions in order to process the 1s and 0s of computing data in a quantum computer.

The new type of qubit, called a “topological qubit,” is stable, smaller, less power-draining and more scalable than a qubit made from a superconducting metal — the most common type of qubit used in quantum computers built by companies such as Google, IBM, and Microsoft itself.

“We took a step back and said ‘Ok, let’s invent the transistor for the quantum age. What properties does it need to have?’,” Chetan Nayak, Microsoft technical fellow and professor of physics at the University of California Santa Barbara, said in a statement. “And that’s really how we got here — it’s the particular combination, the quality and the important details in our new materials stack that have enabled a new kind of qubit and ultimately our entire architecture.”

Related: Quantum simulation breakthrough will lead to ‘discoveries impossible in today’s fastest supercomputers,’ Google scientists claim

The fabrication of this QPU was only possible after researchers, for the first time, used the architecture to definitively observe and control an enigmatic subatomic particle with special properties called the “Majorana fermion,” or “Majorana zero mode” (MZM), theorized by mathematician Ettore Majorana in 1937.

Scientists have previously tried to create Majorana fermions to use for a new kind of quantum computing. Explorations of the Majorana fermion and its proposed use in quantum computers span many years, including a reported discovery of the particle in 2012 and in April 2024. Scientists in June 2023 also published a study reporting the discovery of the topological state of matter.

Majorana’s theory proposed that a particle could be its own antiparticle. That means it’s theoretically possible to bring two of these particles together, and they will either annihilate each other in a massive release of energy (as is normal) or can coexist stably when pairing up together — priming them to store quantum information.

These subatomic particles do not exist in nature, so to nudge them into being, Microsoft scientists had to make a series of breakthroughs in materials science, fabrication methods and measurement techniques. They outlined these discoveries — the culmination of a 17-year-long project — in a new study published Feb. 19 in the journal Nature.

This is a ‘transistor for the quantum age’

Chief among these discoveries was the creation of this specific topoconductor, which is used as the basis of the qubit. The scientists built their topoconductor from a material stack that combined a semiconductor made of indium arsenide (typically used in devices like night vision goggles) with an aluminum superconductor.

The researchers needed the right combination of these components to trigger the desired transition into the new topological sate of matter. They also needed to create very specific conditions to achieve this — namely, temperatures near absolute zero and exposure to magnetic fields. Only then could they usher MZMs into existence.

To construct one qubit, which is less than 10 microns in size — much smaller than superconducting qubits — the scientists arranged a set of nanowires into an H shape, with two longer topoconducting wires joined in the center by one superconducting wire. They next induced four MZMs to exist on all four points of the H by cooling the structure down and tuning it with magnetic fields. Finally, to measure the signal when the device would be operational, they connected the H with a semiconductor quantum dot — equivalent to a small capacitor that carries charge.

Topoconductors differ from superconductors in the way they behave when burdened with an unpaired electron. In superconductors, electrons usually pair up — known as Cooper pairs — with an odd number of electrons (any unpaired electron) requiring a massive amount of energy to accommodate, or enter an excited state. The difference in energy between the ground state and the excited state is the basis for the 1s and 0s of data in superconducting qubits.

Like superconductors, topoconductors use the presence or absence of an unpaired electron as the 1s and 0s of computing data, but the material can “hide” unpaired electrons by sharing their presence among the paired electrons. This means there is no measurable energy difference when unpaired electrons are added into the system, making the qubit more stable at the hardware level and protecting the quantum information. However, it also means it’s harder to measure the qubit’s quantum state.

This is where the quantum dot comes in. The scientists beam a single electron from the quantum dot into one end of the wire, through the MZM, and it emerges from the other end, through another MZM. By blasting the quantum dot with microwaves as this happens, the returning reflection carries an imprint of the quantum state of the nanowires.

The accuracy of this measurement is approximately 99%, the scientists said in the study, noting that electromagnetic radiation is one example of an external factor that triggers an error once per millisecond, on average. The scientists said this is rare and indicates that the inherent shielding in the new type of processor is effective at keeping radiation out.

The path to a million qubits

“It’s complex in that we had to show a new state of matter to get there, but after that, it’s fairly simple. It tiles out. You have this much simpler architecture that promises a much faster path to scale,” Krysta Svore, Microsoft’s principal research manager, said in the statement.

Svore added this new qubit architecture, called the “Topological Core,” represents the first step on the path to creating workable 1 million-qubit quantum computers — likening its creation to the shift from building computers using vacuum tubes to transistors in the 20th century.

This is thanks to the smaller size and higher quality of the qubits, alongside the ease with which they can scale because of the way the qubits fit together like tiles, the scientists said in the study.

In the next few years, the scientists plan to build a single chip with a million physical qubits, which will, in turn, lead to useful scientific breakthroughs in fields like medicine, materials science and our understanding of nature that would be impossible to make using the fastest supercomputers.

The quantum chip does not work in isolation, however. Rather, it exists in an ecosystem alongside a dilution refrigerator to achieve extremely cold temperatures, a system that manages control logic, and software that can integrate with classical computers and artificial intelligence (AI). The scientists said that optimizing these systems so that they can work at a much bigger scale will take years of further research. But this timeline may be expedited with further breakthroughs.

“Those materials have to line up perfectly. If there are too many defects in the material stack, it just kills your qubit,” Svore said in the statement. “Ironically, it’s also why we need a quantum computer — because understanding these materials is incredibly hard. With a scaled quantum computer, we will be able to predict materials with even better properties for building the next generation of quantum computers beyond scale.”