For the first time, scientists have created detailed, 2D maps of the sun’s outermost atmosphere. This feat was accomplished using data from NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which has been dipping in and out of the sun’s atmosphere, called the corona, since 2021.

Parker is the first craft in history to fly so close to a star. This ability is largely thanks to its extraordinary heat shield, which can withstand temperatures in excess of 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit (1,370 degrees Celsius). The sun’s corona is much hotter — around 1 million to 3 million F (555,000 C) — but it is extremely diffuse, meaning that objects moving swiftly through it don’t encounter very many superheated particles. This allows Parker to skim through the outer boundary of the corona for brief periods.

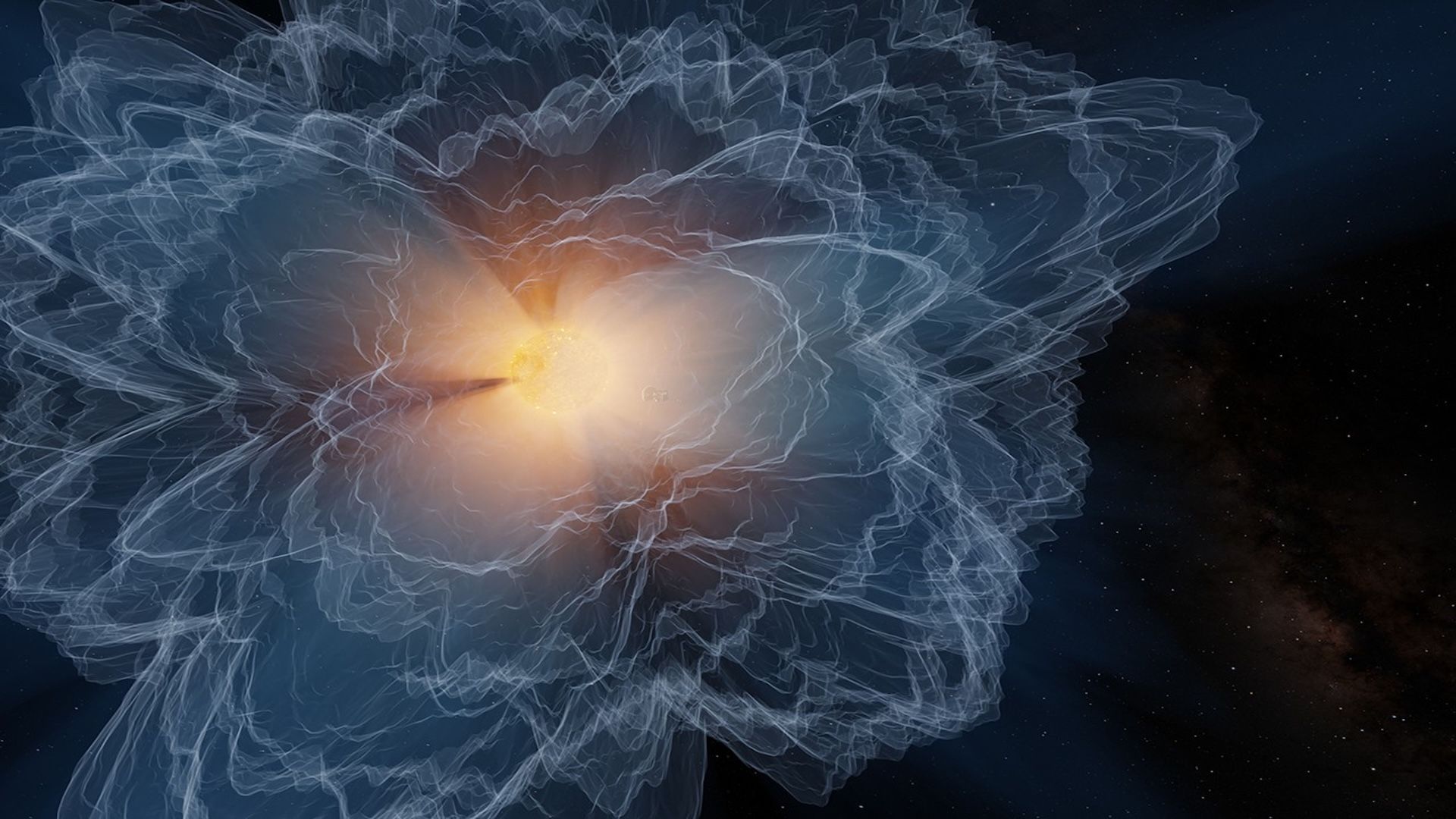

This boundary — beyond which solar particles get swept into the 1 million-mph (1.6 million km/h) stream of solar wind that constantly flows from our star — is known as the Alfvén surface. This invisible border is the point of no return for solar particles, and its precise shape and nature have remained largely mysterious — until now.

The new maps, made using data from Parker’s Solar Wind Electrons Alphas and Protons instrument, define the shape of the Alfvén surface in greater detail than ever before. Using data from the past seven years, Parker’s maps prove that the Alfvén surface routinely changes its shape and extent depending on how active the sun is. (The sun follows a roughly 11-year activity cycle, with solar maximum — its peak period — bringing powerful solar flares and space weather more frequently.)

The new maps reveal that the Alfvén surface grows “spikier” and more turbulent as the sun becomes more active, as it has been for the past several years. This is important for understanding exactly where the outer edge of the sun’s atmosphere is and how solar winds behave in relation to it. But it could also help scientists protect the technologies we use on Earth.

Systems like GPS, communication radios and power grids are susceptible to disruption from powerful solar flares. The ability to predict when such a flare might occur, or even how strong it will be, could help the people who operate these systems brace for a potential disruption.

Parker completed its 25th flyby of the sun in September, matching its record close distance of 3.8 million miles (6.2 million kilometers) from the sun’s surface, according to NASA. The probe also matched its record speed of 427,000 mph (687,000 km/h), making it the fastest human-made object in history. The speed and distance records were first set in December 2024 and have been tied on three subsequent flybys (in March, June and September 2025).

Parker’s primary mission has now ended, but the probe remains in good condition and will continue collecting data at least through mid-2029.