A close relative of the deadly Nipah and Hendra viruses has been detected in North America for the first time — specifically, in the U.S. state of Alabama.

The pathogen, which scientists have named Camp Hill virus, was detected in four northern short-tailed shrews (Blarina brevicauda). The animals were caught in 2021 near a town of the same name in Tallapoosa County, Alabama. After being captured for a study, the animals had been dissected and their organs frozen for later analyses; it was in those analyses that the virus was discovered.

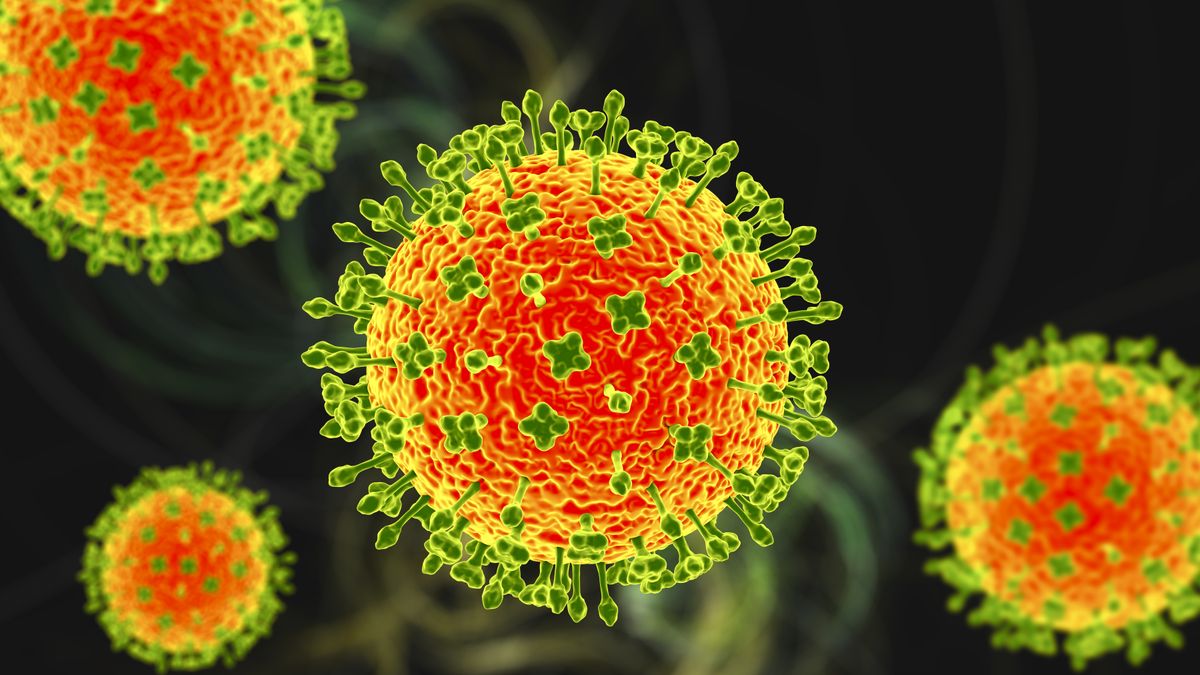

Camp Hill virus is a type of henipavirus, a broad group of viruses that typically infect bats but have been known to “spill over” into various mammals, including humans. In people, henipaviruses can cause severe respiratory illness and a type of inflammation of the brain known as encephalitis.

Prominent henipaviruses known to infect humans include Hendra virus and Nipah virus. The former virus was first detected in Australia in 1994 and has a case-fatility rate of around 60%. The latter germ has caused disease outbreaks across Southeast Asia since being initially detected in Malaysia in 1998, and it kills between 40% and 70% of people infected.

Related: Deadly Nipah virus kills boy in India, prompts worries over outbreak

The detection of Camp Hill virus is significant because it marks the first time a henipavirus has been detected in North America. That’s according to the scientists who discovered it, who released a paper Jan. 17 in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The discovery raises concerns that henipaviruses may be more widespread than once thought. In particular, it provides evidence that B. brevicauda shrews — which can be found across central and eastern North America — can harbor these types of viruses, along with other germs already confirmed to cause human disease. It’s possible that Camp Hill virus may pose a risk to humans, perhaps spreading through direct contact with infected animals or their feces and urine, the researchers suggested.

However, despite these possible concerns, the authors of the new paper have cautioned against leaping to such conclusions.

“There is no evidence to suggest that the provisionally named Camp Hill virus has infected humans, and the likelihood of it doing so remains unknown but is likely low,” lead study author Rhys Parry, a molecular virologist at the University of Queensland in Australia, told Live Science in an email.

Although Camp Hill virus belongs to the same genus as Hendra and Nipah viruses — called Henipavirus — it is genetically distinct from both of them, he emphasized. By comparison, Camp Hill virus is more closely related to other shrew-borne henipaviruses seen in Southeast Asia and Europe than bat-borne henipaviruses like Hendra and Nipah, he said.

This distinction is key because bat-borne henipaviruses tend to infect a wider range of hosts and cause them more harm, and they’ve been known to cause severe disease outbreaks in people, he said.

So far, only one other shrew-borne henipavirus has been identified, and that is Langya virus, Parry said. This virus infected 35 people in China between 2018 and 2021, causing symptoms such as fever, fatigue and cough and in rarer cases, impaired liver and kidney function. But importantly, no deaths were reported.

It’s currently unknown whether the B. brevicauda shrews in North America are able to spread Camp Hill virus to humans. They usually inhabit woodland areas where direct encounters with humans would be somewhat rare, the study authors wrote.

Notably, B. brevicauda shrews have been found to carry other viruses that can potentially spill over to people, but these have never made the leap from these critters to humans.

“Given that B. brevicauda shrews already host other zoonotic viruses, such as Powassan virus and Camp Ripley virus, and that veterinary professionals already handle them with appropriate biosafety measures, no additional precautions are required,” Parry said.

Future research should instead focus on trying to isolate the Camp Hill virus and decipher how many types of animals it can and has infected, he said. This information could then be used to better assess the potential risk of a spillover to humans.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.