The dominant Manchester United dynasty of the 2000s can attribute their success to several factors. Most pertinently, they had world-class players, such as Wayne Rooney, Cristiano Ronaldo and Rio Ferdinand, who were coached by Sir Alex Ferguson, arguably the greatest manager in English football history.

There was also Old Trafford, the largest club stadium in English football and a ground that Jamie Carragher, writing in the Telegraph, said can make “many players freeze”. They might have even got the odd favourable decision from the officials.

But there’s one thing United players insist was an underrated secret ingredient: video games.

“We always used to play a game at Man United on the PSP (PlayStation Portable) called SOCOM — an old-school Call of Duty. We used to spend hours on this game,” said former United and England goalkeeper Ben Foster on his Fozcast podcast.

“I actually still say part of us winning and our culture was down to that game. We were all together in it, like hating each other at times and arguing, people throwing PSPs, it was unbelievable.”

SOCOM (or SOCOM U.S. Navy SEALs: Fireteam Bravo, to use its full name) was a massive hit at United’s Carrington training ground and on away days and pre-season tours, particularly within the club’s younger core.

The ‘third-person tactical shooter’ video game franchise sold more than 10 million copies across eight releases. There were eight players on two teams — sometimes United players would have to wait their turn as places were often oversubscribed — and the regulars, including Foster, Ferdinand (nicknamed ‘Brrrap’), Rooney (aka Jack Bauer, after the fictional protagonist of the 24 television series) and Ronaldo, would have team talks before the game, assigning roles to each player.

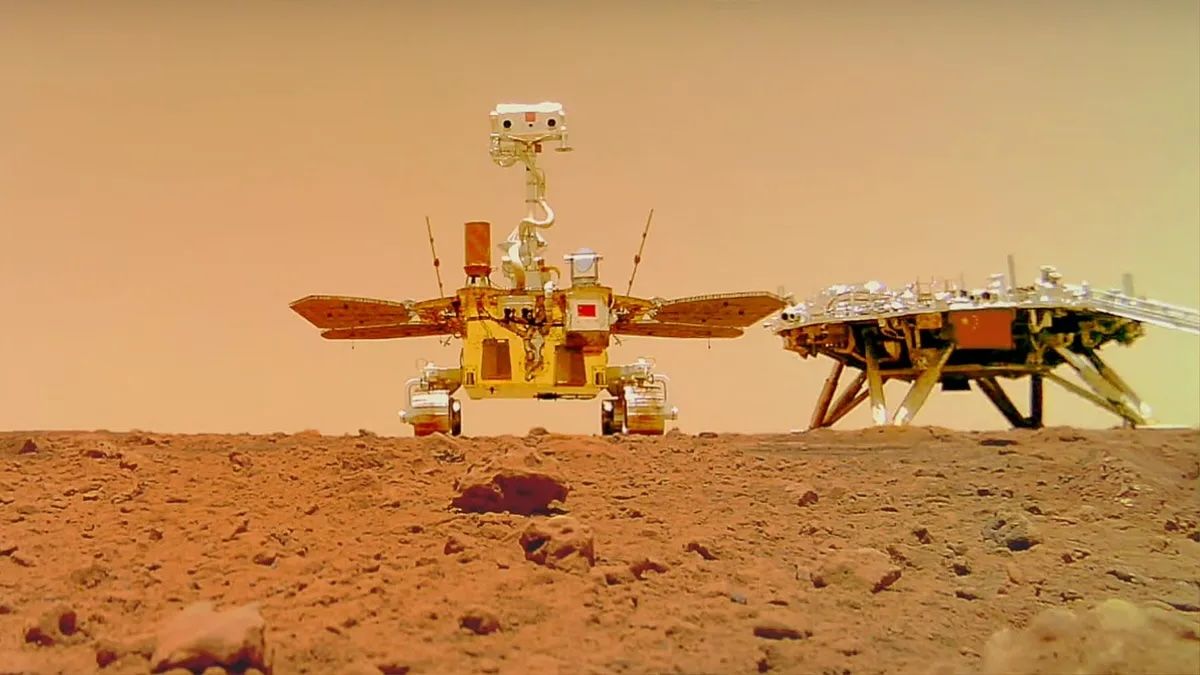

Former United players credit playing SOCOM on the PSP for their strong team bond (David Becker/Getty Images)

“People were probably wondering what was going on when they were seeing Vida (Nemanja Vidic) and Sheasy (John O’Shea, or ‘Cobra’) pulling out imaginary rocket launchers after they’d scored goals in important games in the Champions League, but it was just our little in-joke, our way of having a laugh about the stuff we’d been doing together,” Wes Brown, who was part of United’s 2008 Champions League-winning side, said on the club website.

“We even took it to England (international duty) with us and all the Chelsea lads would be playing it. We used to play United versus Chelsea on SOCOM, and come on, who do you think won those? Let’s put it this way: many a Chelsea PSP was broken in frustration.”

Since United’s golden era of success under Ferguson, the video game industry has exploded, and its place in the football world reflects that.

Gone are the days when SOCOM was the game of choice at the elite level; EA Sports FC (previously known as FIFA) and Call of Duty are now the chief titles within football’s most popular pastime.

Given the shared nature of the video game and the sport (and that they can play using themselves and their team-mates), EA FC naturally holds a significant market share among footballers. During the first Covid-19 lockdown in 2020, EA Sports hosted the ‘Stay and Play Cup’ on FIFA involving players from clubs across Europe, including Manchester City’s Phil Foden, Real Madrid and Brazil forward Vinicius Junior and Paris Saint-Germain full-back Achraf Hakimi, then on loan at Borussia Dortmund.

Trent Alexander-Arnold, another of the entrants for that tournament, which was won by Denmark international Mohamed Daramy, remains a keen player. In April, he assembled a ‘Pro Clubs’ team to face a squad of YouTubers and streamers (occasionally including Rooney before he was appointed Plymouth Argyle boss in May) — with videos of their game amassing over 1.3 million views across two YouTube channels. This summer, members of Spain’s Euro-winning side, including close friends Lamine Yamal and Nico Williams, made a Pro Clubs team to pass the time on their month-long odyssey to glory.

For football players, video games are an ideal companion to their high-pressure lifestyle.

Alexander-Arnold is a fan of EA Sports FC (Carl Recine/Getty Images)

“Gaming is part of the youth culture,” says Benjamin Reichert, a former professional footballer in Germany and founder of esports team SK Gaming. “Football players and professional athletes get to that level because they want to win. They want to compete every day. Back in the day, when we weren’t gaming, we did other things. We played cards, we played table tennis — it’s all about being the best, competing against each other and having fun.”

It’s not just the young players, either. Guadalajara striker Javier Hernandez, 36, formerly of Manchester United and Real Madrid, operates an account with nearly one million followers on the live-streaming platform Twitch. He primarily records himself playing Call of Duty but dabbles in other titles, including Resident Evil Village or Five Nights at Freddy’s 4.

Other notable stars with streaming accounts include Neymar, 32, and retired Argentina striker Sergio Aguero, 36, who has 4.8m followers on Twitch.

“In the biggest sports, there’s so much pressure,” says Reichert. “You have to compete or show every day the best version of you to be in the starting XI on the weekend. Having something where they can come down by playing with friends or online just allows them to have fun.

“It’s interesting when you see players streaming or in interviews; you can feel that they are relaxed and free to speak or answer questions that they would never have otherwise. It’s another atmosphere, and I think it’s really important for them.”

Reichert, who played in the German second and third tiers across an 11-year career as a professional, is considered a pioneer in the world of sports gaming. In 1997, Reichert founded an esports team with other professional players and his brothers, more than a decade before esports became a significant part of the video game industry. He is best known for co-founding (alongside former Bundesliga midfielder Moritz Stoppelkamp) INDIGAMING, the developers of the POGA ‘console in a box’ that is quickly becoming the travel essential for elite football players.

If you have watched England’s ‘arrivals’ videos on YouTube or are following some of the game’s biggest stars on Instagram, you might not be aware you have watched someone wheeling around a POGA suitcase. It is a suitcase or a briefcase with a built-in console and monitor that allows players to take their gaming on the go.

Conor Gallagher 🤝 @EASPORTSFC

Watch the #ThreeLions arrivals here 👇

— England (@England) November 12, 2024

Reichart says: “We were big gamers for years, so it was necessary to have a tool to play wherever we were. As a player, you are always on the run. Away games, journeys, pre-season, whatever, and it was nearly impossible to set up, for example, at the hotel, because the HDMI port might have been disconnected because of the hotel’s entertainment.

“Then Moritz, Ingo (Bohm, INDIGAMING’s head of commercial operations) and I came together and created a prototype. We rolled it out through our friends and network with the football players here in Germany. Then it moved from Germany to the UK and through the big leagues around Europe.”

Reichert (right) helped create the POGA system (Bongarts/Getty Images)

Raheem Sterling was among the first high-profile players to inadvertently promote POGA through his Instagram, showing him and his friend playing FIFA on the train in 2018. Since then, the system has taken off within elite football.

In the past year, Yamal, Mohamed Salah and England and Arsenal players Bukayo Saka and Declan Rice have been pictured gaming on the system. Manchester United forward Marcus Rashford and Atletico Madrid midfielder Saul Niguez have enthused about it.

The POGA system typically contains a built-in console (either a PlayStation or Xbox) and a gaming monitor. They are expensive — prices start at £824; or £1,274 with a PlayStation console (or $1,047 and $1,619 in the United States) — and are not likely to become the norm for the average person. Alternatives from companies such as GeeGee Gaming exist too but POGA’s place within the football world is firmly established.

That’s not to say that football clubs have been entirely on board with the growing influence video games are playing in the lives of their players.

Italy head coach Luciano Spalletti has expressed issues with players playing video games. In February, he suggested one player had stayed up all night playing games and not slept. “That’s not OK,” he said in a press conference. “It’s not the two hours we’re out on the pitch that shows who we are, but the 22 hours either side.”

Spalletti did not name any players, but he dropped Gianluca Scamacca — described by local newspaper Corriere Bergamo as a “PlayStation fanatic” — from his squad for the friendlies against Venezuela and Ecuador in March.

While Jadon Sancho was playing for Borussia Dortmund, German media outlet Bild reported concerns within the club over an alleged habit of spending too much time on his console and similar allegations were directed towards France winger Ousmane Dembele during his time at Barcelona.

Despite the odd time when players get carried away, clubs and national teams recognise the role video games can play in success. Before the POGA boom allowed players to bring their devices on the go, England’s FA set up a console room for the 2018 World Cup. The Fortnite competitions were among the many aspects that improved England’s team spirit, helping them reach their first World Cup semi-final in 28 years.

If it genuinely contributed to the winning culture developed under Ferguson at United, perhaps cautious coaches and front offices are missing an opportunity: allowing your players to play video games could be an underrated formula for success.

(Top photos: Getty Images)