Scientists have detected strange chirping waves — which resemble the dawn chorus of birds — thousands of miles from Earth, and they could pose big problems for future spaceflight.

Chorus waves, named because of their resemblance to birdsong when converted to audio signals, are perturbations in Earth’s electromagnetic field capable of accelerating particles to potentially deadly speeds for spacecraft and astronauts.

Yet while these mysterious waves have been spotted coming from Earth and other planets since the 1960s, scientists previously assumed they only occurred nearby.

Now, in a discovery that challenges existing theories, a new team of researchers has spotted the waves at a distance of 100,000 miles (165,000 kilometers) from Earth, roughly three times further than they were detected before. The researchers published their findings Jan 22. in the journal Nature.

Related: Scientists detect the most powerful cosmic rays ever — and their unknown source could be close to Earth

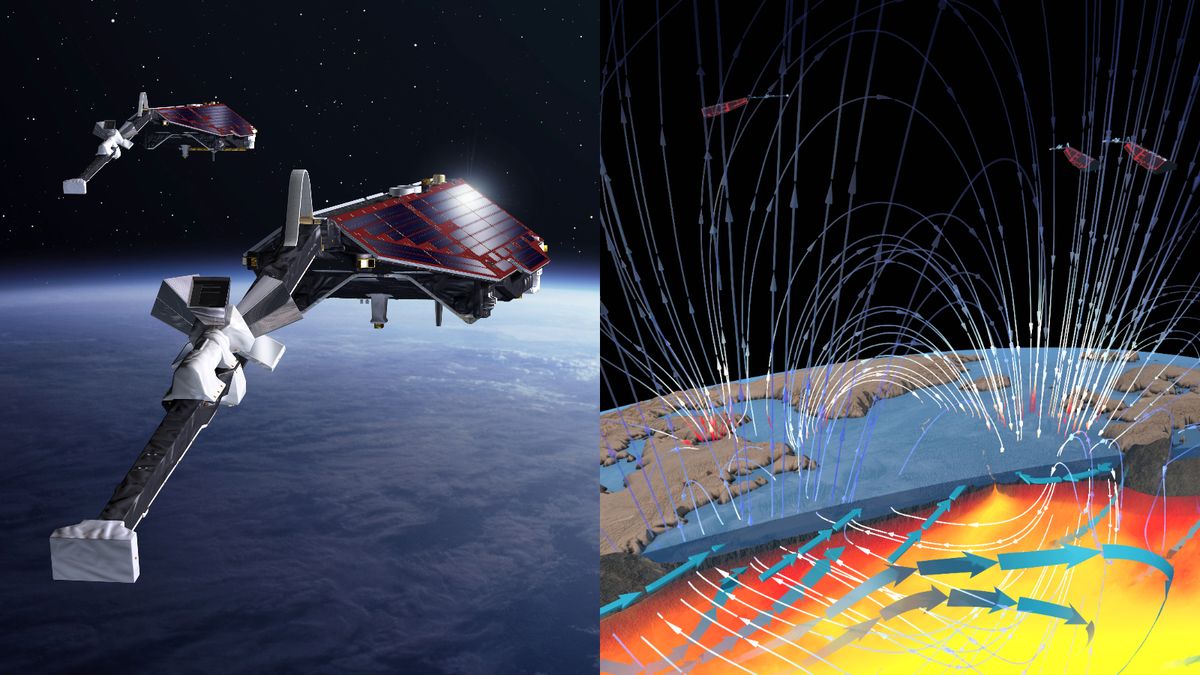

Chorus waves (or whistler-mode chorus waves) are bursts of energy lasting just a few tenths of a second that ping across Earth’s magnetosphere, the magnetic field that envelops our planet. The waves were first detected by World War I radio operators who heard them while listening for enemy signals.

In the decades since, chorus waves have been picked up by radio receivers, as well as by NASA’s Van Allen Probe spacecraft, which detected the chirrups coming from Earth’s radiation belts. The waves have also been spotted surrounding Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune (all planets with global magnetic fields) as well as Mars and Venus, which do not have magnetic fields.

Scientists are still debating what causes chorus waves, but the most popular theory is that they are formed by an effect called plasma instability. Within curved dipoles, such as common bar magnets and planetary magnetic fields, electrons belched out by the sun are typically trapped along magnetic field lines. Typically, particles move along these lines in an orderly, spiral fashion.

But sometimes perturbations in the field disrupt this neat file, causing the electrons to generate chorus waves that resonate with the electrons and accelerate them to deadly, near-light speeds. According to this theory, the curved nature of these dipoles enables chorus waves to travel from pole to pole, producing their signature chirp.

Yet these new waves, detected by NASA’s Magnetospheric Multiscale satellites, were found in a relatively flat region of Earth’s magnetosphere, implying that they were instead produced by changes in frequency across the field.

To better study the waves and what could be producing them, the researchers have suggested better monitoring of incoming plasma belches from the sun and how they interact with Earth’s magnetosphere. This could lead to answers that may prove vital for ensuring that future satellites, astronauts and deep space missions to Mars and beyond aren’t fatally struck by high-speed electrons.

“The discovery doesn’t rule out the existing theory, because the expected magnetic field gradients could still be present, but it means that scientists need to take a closer look,” Richard Horne, the head of space weather at the British Antarctic Survey, who was not involved in the study, wrote in a commentary on the research. “It is a surprising result in a surprising region, and it prompts further investigation of chorus waves in regions in which Earth’s magnetic field deviates substantially from a dipole.”