Scientists have unlocked the secret sex lives of sharks off North Carolina by examining gruesome bite wounds inflicted during the act.

Shark sex is not for the faint-hearted, requiring them to press their bellies together while the male penetrates the female. This happens swiftly for small sharks, but larger species are less nimble and struggle to hold the position, so the male often grasps the female with his teeth, leaving bloody wounds on her body in the process.

Many males don’t leave unscathed either. Some females bite back during sex, according to a new study, published Dec. 4 in the journal Environmental Biology of Fishes.

By examining bite wounds in male and female sharks, researchers can pinpoint the timing and location of mating activity that remains largely hidden in the wild.

“Observations of mating for any shark or ray species are very rare so we used mating wounds as indirect evidence for reproductive behavior,” study lead author Jennifer Wyffels, a researcher at Ripley’s Aquariums and the University of Delaware, told Live Science in an email. “Sharks and rays use their mouths to hold and position females and therefore, mating wounds are common during the reproductive season.”

Related: ‘Mega momma’ great white shark killed on drumline may reveal secrets about iconic predator

But detailed observations of mating wounds are scarce in the scientific literature, so researchers know little about this aspect of shark reproduction, Wyffels said.

For the study, Wyffel and colleagues examined mating wounds in sand tiger sharks (Carcharias taurus) — a critically endangered species that grows up to 10 feet (3 meters) long and inhabits coastal areas worldwide.

The researchers first observed a group of sand tiger sharks in an aquarium, where they witnessed mating activity that resulted in severe injury to a female. The deepest wound cut through the female’s skin and exposed the underlying muscle, but the lesion was quick to heal, the researchers noted in the study.

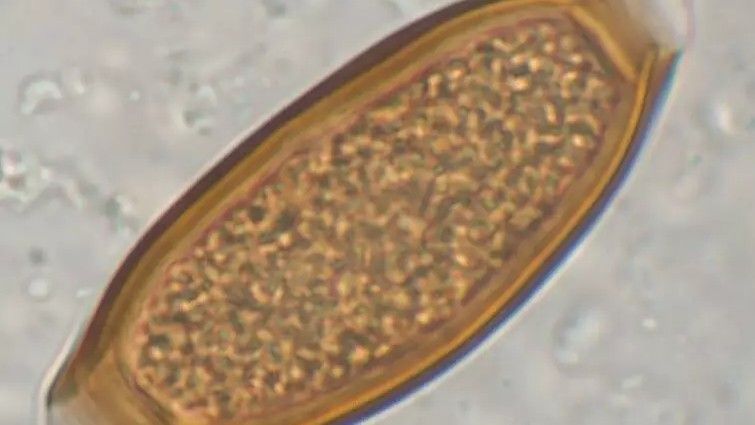

Next, based on these data, the researchers established a scale from 1 to 4 to describe the severity and healing stages of shark mating wounds — with 1 describing fresh wounds, 2 and 3 describing intermediate levels of healing, and 4 describing initiation of scarring.

The team then applied this healing scale to pictures of sand tiger sharks from the database Spot A Shark U.S.A., which encourages citizen scientists to submit images of C. taurus snapped along the Northwest Atlantic coast. In total, the researchers analyzed 2,876 photographs of 686 sand tiger sharks taken between 2005 and 2020 off the coast of North Carolina.

The images revealed that coastal North Carolina is a hotspot for sand tiger shark sex.

The researchers detected an increase in stage 1 wounds in late May, marking the start of a voracious mating season in the region. The peak leveled off in July, indicating that mating is less frequent and/or less aggressive then, according to the study.

“By mid to late summer, mating has ceased based on the lack of stages 1 and 2 mating wounds on females,” the researchers wrote in the study.

But females stuck around after the end of the mating season, photographs taken in late summer revealed. Many of these remaining females had stage 3 and 4 wounds, indicating that the region is both a mating habitat and a gestation habitat for pregnant females, according to the study.

The results unveil little-known aspects of shark reproduction, but they also confirm that sharks have unusually fast healing rates. Anecdotal reports have long suggested that sharks can survive extreme injuries and emerge with little to no scarring, but observations are rare. Here, the deep wounds of the aquarium female closed after just 22 days, and scarring finished 85 days post injury, the study noted.

“By combining aquarium and wild sand tiger shark wound healing observations, we were able to describe wound stages and a timeline for healing for this species,” Wyffels said. “This information was used to infer the mating season for wild sand tiger sharks.”