In this adapted excerpt from “The Future of Language: How Technology, Politics and Utopianism are Transforming the Way We Communicate” (Bloomsbury, 2023), author Philip Seargeant examines brain computer interfaces designed to help locked-in patients communicate, and why technology companies like Facebook are using them as the basis for wearable devices that could transform, for good or ill, how everyday users communicate.

When my grandmother suffered a stroke some years ago, for several days she completely lost the ability to communicate. The whole left side of her body, from her scalp to the sole of her foot, was paralysed, and for those first few days she could barely move. She couldn’t talk at all; the best she could manage, if she wanted to draw our attention to something, was to gesture vaguely with her one good hand. Once the medical team had settled her in the ward, she kept lifting her finger to her lips with an increasingly exasperated look in her eyes. It took me an age to realize that she was indicating she wanted something to drink. She’d been lying helpless on the floor of her house for almost twenty-four hours before she was discovered, and by now she was desperately thirsty.

When the hospital’s speech therapist came around to visit a day or two later she gave us a ‘communication board’. This was basically just a piece of cardboard, slightly tattered at the edges, with the letters of the alphabet printed on one side. On the other side there were a few simple pictures – images of a bottle of pills, a cluster of family members, a vicar, that sort of thing. If my grandmother wanted to tell us something, now she pointed slowly from letter to letter, spelling out key words. It was a tortuously slow process, especially with her coordination skills still so shaky. It also required a lot of guesswork on the part of the person she was talking to, as they had to try to piece together, from isolated words, the full meaning of what she was trying to convey.

Finding ways to make the brain speak is at the heart of research into what is known as brain-computer interface (or BCI) technology, an area of neuroscience that’s investigating how we can control machines with our minds. BCI technology works by the use of sensors, placed either in or around the brain, which pick up neural activity that can then be read by a computer and used to operate external devices. It’s a means of establishing a communication path between computer and brain which doesn’t rely on the muscular movement that has hitherto allowed for the interface between the two. It’s a form of real-life mind control, allowing people to execute simple tasks using nothing more than the power of thought. And one of the tasks that’s currently being worked on by researchers is the idea of ‘typing’ with the brain.

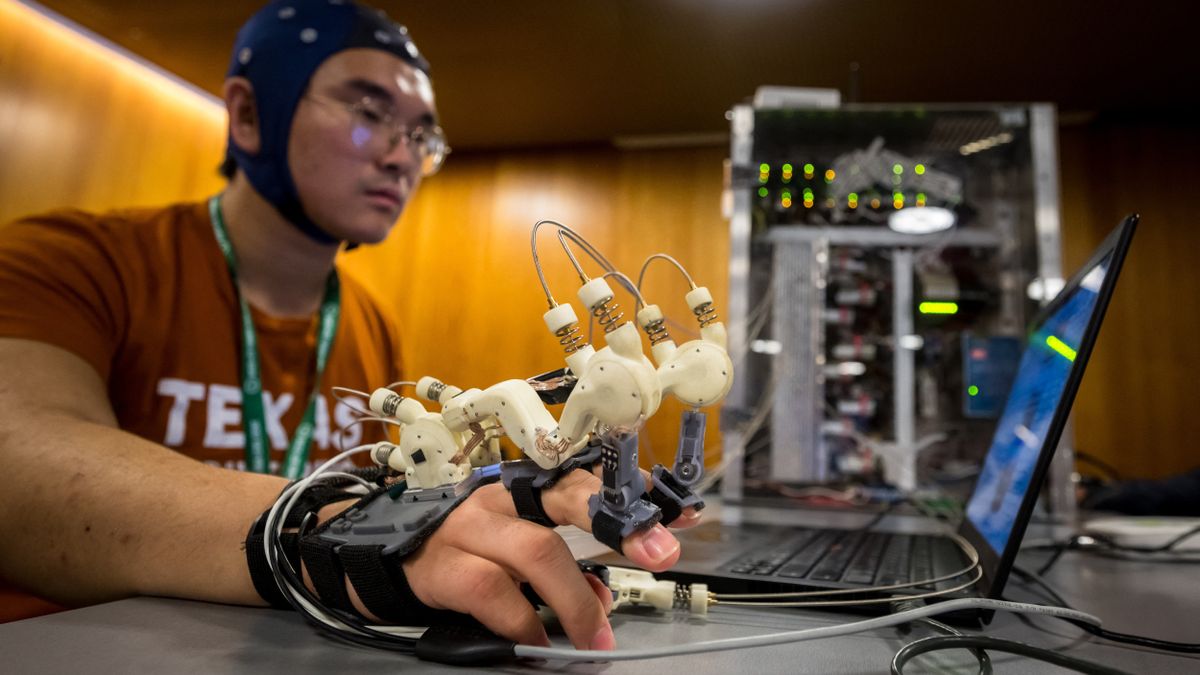

Studies show that this sort of BCI technology can provide a way for patients with locked-in syndrome to communicate via a BCI speller, or for paraplegics to control prosthetic limbs or computerized devices. It’s early days for this sort of research, but already there are encouraging signs of what might be possible. In 2017, a small group of participants on a project in the United States, all of whom were paralysed (one had suffered a spinal injury; the others had Lou Gehrig’s disease), were able to ‘type’ with their brains at somewhere between three and eight words per minute. Okay, so this isn’t particularly fast. A professional typist averages up to eighty words per minute, and smartphone users can manage about thirty-eight words per minute. But it already rivals a patient struggling to get by with a ‘communication board’. And it’s infinitely better than having no access to communication at all.

The participants in this particular study had tiny electrodes implanted on the surfaces of their brains, penetrating about a millimetre into the motor cortex. These were connected to a series of wires protruding from their heads which were then attached to a network of cables. For casual, everyday use this is clearly a bit unwieldy. But, as I say, it’s early days for the research and the aim is to achieve similar results through the use of wireless implants or ‘non-invasive’ devices such as headsets placed over the scalp (although the closer one can get to the signal that needs to be read, the clearer that signal is).

The potential, and the market, isn’t limited simply to helping those with speech impairments. Unsurprisingly, both the entertainment industry and the military see great possibilities in the technology. Then there are the big tech companies who are currently ploughing huge amounts of money into this research. They see it as a universal technology which will revolutionize the way we connect both with each other and, possibly more importantly (at least from their point of view), with our digital devices. In 2019 Facebook Labs introduced their vision for a future enhanced by BCI technologies by inviting us to ‘imagine a world where all the knowledge, fun, and utility of today’s smartphones were instantly accessible and completely hands-free’. This imaginary world is one in which the multiple capabilities of the smartphone aren’t limited to a little black box you manipulate with your hand. Instead, the plan is for a non-invasive system that you can wear on your head. For Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook, non-invasive solutions are preferable not only because they sidestep the difficulties that are caused by the body rejecting physical implants (which is proving to be a real problem for many projects) but also because, as he somewhat sardonically noted to his colleagues, he’d like to avoid having to give testimony at a congressional hearing on allegations that Facebook now wants to perform brain surgery on its users.

The Facebook plan is for a wearable BCI device which, they say, will be ‘realized in the ultimate form factor of a pair of stylish, augmented reality glasses’. Among the many things this will allow you to do is to ‘type’ at 100 words per minute. Should this be achievable, not only would it outstrip current mind-typing top speed of eight words per minute but it would also better what all smartphone users and most professional typists can manage.

It’s an ambitious vision for wearable tech. Facebook’s current smart glasses – their collaboration with Ray Ban for the ‘Ray Ban Stories’ – are a rather more prosaic appendage to the smartphone. They can take photos and video, play music and operate as a phone receiver. Other companies developing smart glasses have more augmented reality features embedded in their products. But at the moment, probably the most dramatic impact of what’s available now isn’t going to be what you can do so much as how and where you can do it, and what this means for our ideas of privacy. Facebook provides a checklist of ethical pointers that customers might want to take into consideration – turn the glasses off in the locker room or public bathroom; ‘be mindful of taking photos around minors’ – but this seems just to highlight potential problems rather than solving them.

There are similar concerns about the direction in which BCI development might take. Concerns about what a world in which everyone’s brain activity is hooked up to the internet would look like, and the implications it would have not only for privacy but also for security and mental wellbeing. Facebook may be trying to sound a relentlessly positive note in its press release, but for lots of people today the smartphone is no longer simply a symbol of ‘knowledge, fun and utility’. It’s also a source of addiction, distraction and overwork. So the idea of having its equivalent plugged directly into your brain (or even just resting on the bridge of your nose as a pair of stylish, augmented reality glasses) isn’t without its worries. The dystopian possibilities seem endless. To give just a single example, one of the many things that BCI technology is able to do is monitor your levels of concentration. As one tech writer has suggested, it’s not hard to imagine a world where companies decide to exploit this by creating systems which track their employees’ brain data as part of their performance evaluations. In a world in which companies are already monitoring everything from their employees’ computer use to their toilet breaks, it would only be a small step to including neural read-outs of their attention levels as well. You’d never again be able to casually rest your head on your hands as if in deep thought while surreptitiously taking a short nap, as the BCI data would be there to betray you.

But there are also questions of what this sort of technology will mean for how we actually communicate, and for what the future of language will look like. As we’ve seen, new communications technologies never simply replace old ones without also bringing about various changes – changes in the way we relate to one another, in the look of the language we use and in the shape of the society in which we live.

Excerpted from The Future of Language. Copyright © 2023 by Philip Seargeant.

Published by Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing.